sidebarDepth: 3

sidebar: auto

Artist tutorial

Using Artist objects to render on the canvas.

There are three layers to the matplotlib API.

- the

matplotlib.backend_bases.FigureCanvasis the area onto which the figure is drawn - the

matplotlib.backend_bases.Rendereris the object which knows how to draw on theFigureCanvas - and the

matplotlib.artist.Artistis the object that knows how to use a renderer to paint onto the canvas.

The FigureCanvas and

Renderer handle all the details of

talking to user interface toolkits like wxPython or drawing languages like PostScript®, and

the Artist handles all the high level constructs like representing

and laying out the figure, text, and lines. The typical user will

spend 95% of their time working with the Artists.

There are two types of Artists: primitives and containers. The primitives

represent the standard graphical objects we want to paint onto our canvas:

Line2D, Rectangle,

Text, AxesImage, etc., and

the containers are places to put them (Axis,

Axes and Figure). The

standard use is to create a Figure instance, use

the Figure to create one or more Axes or

Subplot instances, and use the Axes instance

helper methods to create the primitives. In the example below, we create a

Figure instance using matplotlib.pyplot.figure(), which is a

convenience method for instantiating Figure instances and connecting them

with your user interface or drawing toolkit FigureCanvas. As we will

discuss below, this is not necessary — you can work directly with PostScript,

PDF Gtk+, or wxPython FigureCanvas instances, instantiate your Figures

directly and connect them yourselves — but since we are focusing here on the

Artist API we’ll let pyplot handle some of those details

for us:

import matplotlib.pyplot as pltfig = plt.figure()ax = fig.add_subplot(2, 1, 1) # two rows, one column, first plot

The Axes is probably the most important

class in the matplotlib API, and the one you will be working with most

of the time. This is because the Axes is the plotting area into

which most of the objects go, and the Axes has many special helper

methods (plot(),

text(),

hist(),

imshow()) to create the most common

graphics primitives (Line2D,

Text,

Rectangle,

Image, respectively). These helper methods

will take your data (e.g., numpy arrays and strings) and create

primitive Artist instances as needed (e.g., Line2D), add them to

the relevant containers, and draw them when requested. Most of you

are probably familiar with the Subplot,

which is just a special case of an Axes that lives on a regular

rows by columns grid of Subplot instances. If you want to create

an Axes at an arbitrary location, simply use the

add_axes() method which takes a list

of [left, bottom, width, height] values in 0-1 relative figure

coordinates:

fig2 = plt.figure()ax2 = fig2.add_axes([0.15, 0.1, 0.7, 0.3])

Continuing with our example:

import numpy as npt = np.arange(0.0, 1.0, 0.01)s = np.sin(2*np.pi*t)line, = ax.plot(t, s, color='blue', lw=2)

In this example, ax is the Axes instance created by the

fig.add_subplot call above (remember Subplot is just a

subclass of Axes) and when you call ax.plot, it creates a

Line2D instance and adds it to the Axes.lines list. In the interactive ipython session below, you can see that the

Axes.lines list is length one and contains the same line that was

returned by the line, = ax.plot... call:

In [101]: ax.lines[0]Out[101]: <matplotlib.lines.Line2D instance at 0x19a95710>In [102]: lineOut[102]: <matplotlib.lines.Line2D instance at 0x19a95710>

If you make subsequent calls to ax.plot (and the hold state is “on”

which is the default) then additional lines will be added to the list.

You can remove lines later simply by calling the list methods; either

of these will work:

del ax.lines[0]ax.lines.remove(line) # one or the other, not both!

The Axes also has helper methods to configure and decorate the x-axis and y-axis tick, tick labels and axis labels:

xtext = ax.set_xlabel('my xdata') # returns a Text instanceytext = ax.set_ylabel('my ydata')

When you call ax.set_xlabel,

it passes the information on the Text

instance of the XAxis. Each Axes

instance contains an XAxis and a

YAxis instance, which handle the layout and

drawing of the ticks, tick labels and axis labels.

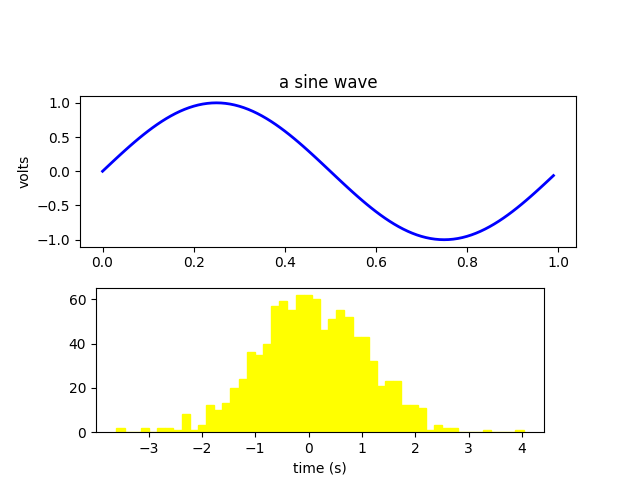

Try creating the figure below.

import numpy as npimport matplotlib.pyplot as pltfig = plt.figure()fig.subplots_adjust(top=0.8)ax1 = fig.add_subplot(211)ax1.set_ylabel('volts')ax1.set_title('a sine wave')t = np.arange(0.0, 1.0, 0.01)s = np.sin(2*np.pi*t)line, = ax1.plot(t, s, color='blue', lw=2)# Fixing random state for reproducibilitynp.random.seed(19680801)ax2 = fig.add_axes([0.15, 0.1, 0.7, 0.3])n, bins, patches = ax2.hist(np.random.randn(1000), 50,facecolor='yellow', edgecolor='yellow')ax2.set_xlabel('time (s)')plt.show()

Customizing your objects

Every element in the figure is represented by a matplotlib

Artist, and each has an extensive list of

properties to configure its appearance. The figure itself contains a

Rectangle exactly the size of the figure,

which you can use to set the background color and transparency of the

figures. Likewise, each Axes bounding box

(the standard white box with black edges in the typical matplotlib

plot, has a Rectangle instance that determines the color,

transparency, and other properties of the Axes. These instances are

stored as member variables Figure.patch and Axes.patch (“Patch” is a name inherited from

MATLAB, and is a 2D “patch” of color on the figure, e.g., rectangles,

circles and polygons). Every matplotlib Artist has the following

properties

Property Description

alpha The transparency - a scalar from 0-1

animated A boolean that is used to facilitate animated drawing

axes The axes that the Artist lives in, possibly None

clip_box The bounding box that clips the Artist

clip_on Whether clipping is enabled

clip_path The path the artist is clipped to

contains A picking function to test whether the artist contains the pick point

figure The figure instance the artist lives in, possibly None

label A text label (e.g., for auto-labeling)

picker A python object that controls object picking

transform The transformation

visible A boolean whether the artist should be drawn

zorder A number which determines the drawing order

rasterized Boolean; Turns vectors into raster graphics (for compression & eps transparency)

Each of the properties is accessed with an old-fashioned setter or getter (yes we know this irritates Pythonistas and we plan to support direct access via properties or traits but it hasn’t been done yet). For example, to multiply the current alpha by a half:

a = o.get_alpha()o.set_alpha(0.5*a)

If you want to set a number of properties at once, you can also use

the set method with keyword arguments. For example:

o.set(alpha=0.5, zorder=2)

If you are working interactively at the python shell, a handy way to

inspect the Artist properties is to use the

matplotlib.artist.getp() function (simply

getp() in pyplot), which lists the properties

and their values. This works for classes derived from Artist as

well, e.g., Figure and Rectangle. Here are the Figure rectangle

properties mentioned above:

In [149]: matplotlib.artist.getp(fig.patch)alpha = 1.0animated = Falseantialiased or aa = Trueaxes = Noneclip_box = Noneclip_on = Falseclip_path = Nonecontains = Noneedgecolor or ec = wfacecolor or fc = 0.75figure = Figure(8.125x6.125)fill = 1hatch = Noneheight = 1label =linewidth or lw = 1.0picker = Nonetransform = <Affine object at 0x134cca84>verts = ((0, 0), (0, 1), (1, 1), (1, 0))visible = Truewidth = 1window_extent = <Bbox object at 0x134acbcc>x = 0y = 0zorder = 1

The docstrings for all of the classes also contain the Artist

properties, so you can consult the interactive “help” or the

matplotlib.artist for a listing of properties for a given object.

Object containers

Now that we know how to inspect and set the properties of a given

object we want to configure, we need to know how to get at that object.

As mentioned in the introduction, there are two kinds of objects:

primitives and containers. The primitives are usually the things you

want to configure (the font of a Text

instance, the width of a Line2D) although

the containers also have some properties as well — for example the

Axes Artist is a

container that contains many of the primitives in your plot, but it

also has properties like the xscale to control whether the xaxis

is ‘linear’ or ‘log’. In this section we’ll review where the various

container objects store the Artists that you want to get at.

Figure container

The top level container Artist is the

matplotlib.figure.Figure, and it contains everything in the

figure. The background of the figure is a

Rectangle which is stored in

Figure.patch. As

you add subplots (add_subplot()) and

axes (add_axes()) to the figure

these will be appended to the Figure.axes. These are also returned by the

methods that create them:

In [156]: fig = plt.figure()In [157]: ax1 = fig.add_subplot(211)In [158]: ax2 = fig.add_axes([0.1, 0.1, 0.7, 0.3])In [159]: ax1Out[159]: <matplotlib.axes.Subplot instance at 0xd54b26c>In [160]: print(fig.axes)[<matplotlib.axes.Subplot instance at 0xd54b26c>, <matplotlib.axes.Axes instance at 0xd3f0b2c>]

Because the figure maintains the concept of the “current axes” (see

Figure.gca and

Figure.sca) to support the

pylab/pyplot state machine, you should not insert or remove axes

directly from the axes list, but rather use the

add_subplot() and

add_axes() methods to insert, and the

delaxes() method to delete. You are

free however, to iterate over the list of axes or index into it to get

access to Axes instances you want to customize. Here is an

example which turns all the axes grids on:

for ax in fig.axes:ax.grid(True)

The figure also has its own text, lines, patches and images, which you

can use to add primitives directly. The default coordinate system for

the Figure will simply be in pixels (which is not usually what you

want) but you can control this by setting the transform property of

the Artist you are adding to the figure.

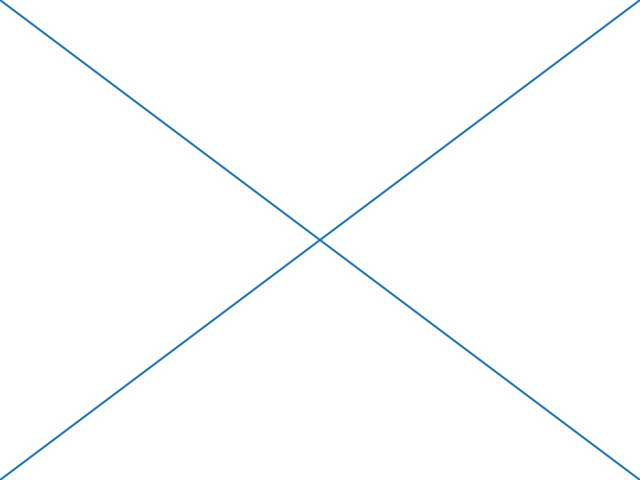

More useful is “figure coordinates” where (0, 0) is the bottom-left of

the figure and (1, 1) is the top-right of the figure which you can

obtain by setting the Artist transform to fig.transFigure:

import matplotlib.lines as linesfig = plt.figure()l1 = lines.Line2D([0, 1], [0, 1], transform=fig.transFigure, figure=fig)l2 = lines.Line2D([0, 1], [1, 0], transform=fig.transFigure, figure=fig)fig.lines.extend([l1, l2])plt.show()

Here is a summary of the Artists the figure contains

Figure attribute Description

axes A list of Axes instances (includes Subplot)

patch The Rectangle background

images A list of FigureImages patches - useful for raw pixel display

legends A list of Figure Legend instances (different from Axes.legends)

lines A list of Figure Line2D instances (rarely used, see Axes.lines)

patches A list of Figure patches (rarely used, see Axes.patches)

texts A list Figure Text instances

Axes container

The matplotlib.axes.Axes is the center of the matplotlib

universe — it contains the vast majority of all the Artists used

in a figure with many helper methods to create and add these

Artists to itself, as well as helper methods to access and

customize the Artists it contains. Like the

Figure, it contains a

Patch

patch which is a

Rectangle for Cartesian coordinates and a

Circle for polar coordinates; this patch

determines the shape, background and border of the plotting region:

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)rect = ax.patch # a Rectangle instancerect.set_facecolor('green')

When you call a plotting method, e.g., the canonical

plot() and pass in arrays or lists of

values, the method will create a matplotlib.lines.Line2D()

instance, update the line with all the Line2D properties passed as

keyword arguments, add the line to the Axes.lines container, and returns it to you:

In [213]: x, y = np.random.rand(2, 100)In [214]: line, = ax.plot(x, y, '-', color='blue', linewidth=2)

plot returns a list of lines because you can pass in multiple x, y

pairs to plot, and we are unpacking the first element of the length

one list into the line variable. The line has been added to the

Axes.lines list:

In [229]: print(ax.lines)[<matplotlib.lines.Line2D instance at 0xd378b0c>]

Similarly, methods that create patches, like

bar() creates a list of rectangles, will

add the patches to the Axes.patches list:

In [233]: n, bins, rectangles = ax.hist(np.random.randn(1000), 50, facecolor='yellow')In [234]: rectanglesOut[234]: <a list of 50 Patch objects>In [235]: print(len(ax.patches))

You should not add objects directly to the Axes.lines or

Axes.patches lists unless you know exactly what you are doing,

because the Axes needs to do a few things when it creates and adds

an object. It sets the figure and axes property of the Artist, as

well as the default Axes transformation (unless a transformation

is set). It also inspects the data contained in the Artist to

update the data structures controlling auto-scaling, so that the view

limits can be adjusted to contain the plotted data. You can,

nonetheless, create objects yourself and add them directly to the

Axes using helper methods like

add_line() and

add_patch(). Here is an annotated

interactive session illustrating what is going on:

In [262]: fig, ax = plt.subplots()# create a rectangle instanceIn [263]: rect = matplotlib.patches.Rectangle( (1,1), width=5, height=12)# by default the axes instance is NoneIn [264]: print(rect.get_axes())None# and the transformation instance is set to the "identity transform"In [265]: print(rect.get_transform())<Affine object at 0x13695544># now we add the Rectangle to the AxesIn [266]: ax.add_patch(rect)# and notice that the ax.add_patch method has set the axes# instanceIn [267]: print(rect.get_axes())Axes(0.125,0.1;0.775x0.8)# and the transformation has been set tooIn [268]: print(rect.get_transform())<Affine object at 0x15009ca4># the default axes transformation is ax.transDataIn [269]: print(ax.transData)<Affine object at 0x15009ca4># notice that the xlimits of the Axes have not been changedIn [270]: print(ax.get_xlim())(0.0, 1.0)# but the data limits have been updated to encompass the rectangleIn [271]: print(ax.dataLim.bounds)(1.0, 1.0, 5.0, 12.0)# we can manually invoke the auto-scaling machineryIn [272]: ax.autoscale_view()# and now the xlim are updated to encompass the rectangleIn [273]: print(ax.get_xlim())(1.0, 6.0)# we have to manually force a figure drawIn [274]: ax.figure.canvas.draw()

There are many, many Axes helper methods for creating primitive

Artists and adding them to their respective containers. The table

below summarizes a small sampling of them, the kinds of Artist they

create, and where they store them

Helper method Artist Container

ax.annotate - text annotations Annotate ax.texts

ax.bar - bar charts Rectangle ax.patches

ax.errorbar - error bar plots Line2D and Rectangle ax.lines and ax.patches

ax.fill - shared area Polygon ax.patches

ax.hist - histograms Rectangle ax.patches

ax.imshow - image data AxesImage ax.images

ax.legend - axes legends Legend ax.legends

ax.plot - xy plots Line2D ax.lines

ax.scatter - scatter charts PolygonCollection ax.collections

ax.text - text Text ax.texts

In addition to all of these Artists, the Axes contains two

important Artist containers: the XAxis

and YAxis, which handle the drawing of the

ticks and labels. These are stored as instance variables

xaxis and

yaxis. The XAxis and YAxis

containers will be detailed below, but note that the Axes contains

many helper methods which forward calls on to the

Axis instances so you often do not need to

work with them directly unless you want to. For example, you can set

the font color of the XAxis ticklabels using the Axes helper

method:

for label in ax.get_xticklabels():label.set_color('orange')

Below is a summary of the Artists that the Axes contains

Axes attribute Description

artists A list of Artist instances

patch Rectangle instance for Axes background

collections A list of Collection instances

images A list of AxesImage

legends A list of Legend instances

lines A list of Line2D instances

patches A list of Patch instances

texts A list of Text instances

xaxis matplotlib.axis.XAxis instance

yaxis matplotlib.axis.YAxis instance

Axis containers

The matplotlib.axis.Axis instances handle the drawing of the

tick lines, the grid lines, the tick labels and the axis label. You

can configure the left and right ticks separately for the y-axis, and

the upper and lower ticks separately for the x-axis. The Axis

also stores the data and view intervals used in auto-scaling, panning

and zooming, as well as the Locator and

Formatter instances which control where

the ticks are placed and how they are represented as strings.

Each Axis object contains a label attribute

(this is what pyplot modifies in calls to

xlabel() and ylabel()) as

well as a list of major and minor ticks. The ticks are

XTick and YTick instances,

which contain the actual line and text primitives that render the ticks and

ticklabels. Because the ticks are dynamically created as needed (e.g., when

panning and zooming), you should access the lists of major and minor ticks

through their accessor methods get_major_ticks()

and get_minor_ticks(). Although the ticks contain

all the primitives and will be covered below, Axis instances have accessor

methods that return the tick lines, tick labels, tick locations etc.:

fig, ax = plt.subplots()axis = ax.xaxisaxis.get_ticklocs()

axis.get_ticklabels()

note there are twice as many ticklines as labels because by

axis.get_ticklines()

by default you get the major ticks back

axis.get_ticklines()

but you can also ask for the minor ticks

axis.get_ticklines(minor=True)# Here is a summary of some of the useful accessor methods of the ``Axis``# (these have corresponding setters where useful, such as# set_major_formatter)## ====================== =========================================================# Accessor method Description# ====================== =========================================================# get_scale The scale of the axis, e.g., 'log' or 'linear'# get_view_interval The interval instance of the axis view limits# get_data_interval The interval instance of the axis data limits# get_gridlines A list of grid lines for the Axis# get_label The axis label - a Text instance# get_ticklabels A list of Text instances - keyword minor=True|False# get_ticklines A list of Line2D instances - keyword minor=True|False# get_ticklocs A list of Tick locations - keyword minor=True|False# get_major_locator The matplotlib.ticker.Locator instance for major ticks# get_major_formatter The matplotlib.ticker.Formatter instance for major ticks# get_minor_locator The matplotlib.ticker.Locator instance for minor ticks# get_minor_formatter The matplotlib.ticker.Formatter instance for minor ticks# get_major_ticks A list of Tick instances for major ticks# get_minor_ticks A list of Tick instances for minor ticks# grid Turn the grid on or off for the major or minor ticks# ====================== =========================================================## Here is an example, not recommended for its beauty, which customizes# the axes and tick properties# plt.figure creates a matplotlib.figure.Figure instancefig = plt.figure()rect = fig.patch # a rectangle instancerect.set_facecolor('lightgoldenrodyellow')ax1 = fig.add_axes([0.1, 0.3, 0.4, 0.4])rect = ax1.patchrect.set_facecolor('lightslategray')for label in ax1.xaxis.get_ticklabels():# label is a Text instancelabel.set_color('red')label.set_rotation(45)label.set_fontsize(16)for line in ax1.yaxis.get_ticklines():# line is a Line2D instanceline.set_color('green')line.set_markersize(25)line.set_markeredgewidth(3)plt.show()

Tick containers

The matplotlib.axis.Tick is the final container object in our

descent from the Figure to the

Axes to the Axis

to the Tick. The Tick contains the tick

and grid line instances, as well as the label instances for the upper

and lower ticks. Each of these is accessible directly as an attribute

of the Tick.

Tick attribute Description

tick1line Line2D instance

tick2line Line2D instance

gridline Line2D instance

label1 Text instance

label2 Text instance

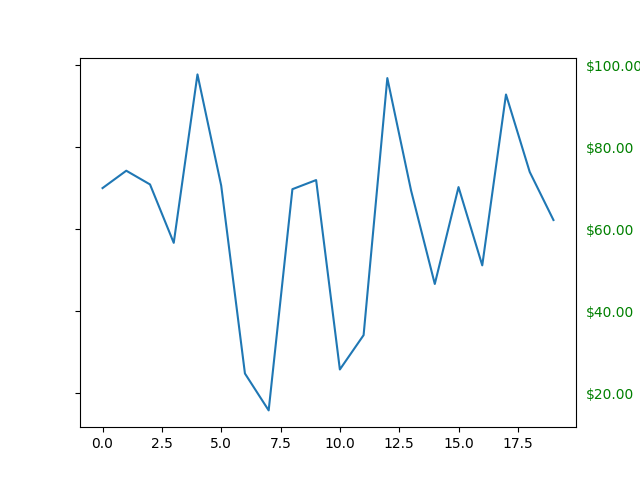

Here is an example which sets the formatter for the right side ticks with dollar signs and colors them green on the right side of the yaxis

import matplotlib.ticker as ticker# Fixing random state for reproducibilitynp.random.seed(19680801)fig, ax = plt.subplots()ax.plot(100*np.random.rand(20))formatter = ticker.FormatStrFormatter('$%1.2f')ax.yaxis.set_major_formatter(formatter)for tick in ax.yaxis.get_major_ticks():tick.label1.set_visible(False)tick.label2.set_visible(True)tick.label2.set_color('green')plt.show()