转载 http://blog.yuanzhaoyi.cn/2018/01/25/500lines-asyncio-web-crawler.html

title: A Web Crawler With asyncio Coroutines author: A. Jesse Jiryu Davis and Guido van Rossum

A. Jesse Jiryu Davis is a staff engineer at MongoDB in New York. He wrote Motor, the async MongoDB Python driver, and he is the lead developer of the MongoDB C Driver and a member of the PyMongo team. He contributes to asyncio and Tornado. He writes at http://emptysqua.re.

A. Jesse Jiryu Davis在纽约为MongoDB工作。他编写了Motor,异步MongoDB Python驱动器,他也是MongoDB C驱动器的首席开发者, 同时他也是PyMango组织的成员之一。他对asyncio和Tornado同样有着杰出贡献。他的博客是 http://emptysqua.re。

Guido van Rossum is the creator of Python, one of the major programming languages on and off the web. The Python community refers to him as the BDFL (Benevolent Dictator For Life), a title straight from a Monty Python skit. Guido’s home on the web is http://www.python.org/~guido/.

Guido van Rossum,Python之父,Python是目前主要的编程语言之一,无论线上线下。 他在社区里一直是一位仁慈的独裁者,一个来自Monty Python短剧的标题。Guido网上的家是 http://www.python.org/~guido/。

Introduction 介绍

Classical computer science emphasizes efficient algorithms that complete computations as quickly as possible. But many networked programs spend their time not computing, but holding open many connections that are slow, or have infrequent events. These programs present a very different challenge: to wait for a huge number of network events efficiently. A contemporary approach to this problem is asynchronous I/O, or “async”.

经典的计算机科学强调高效的算法,尽可能快地完成计算。但是很多网络程序的时间并不是消耗在计算上,而是在等待许多慢速的连接或者低频事件的发生。这些程序暴露出一个新的挑战:如何高效的等待大量网络事件。一个现代的解决方案是异步 I/O。

This chapter presents a simple web crawler. The crawler is an archetypal async application because it waits for many responses, but does little computation. The more pages it can fetch at once, the sooner it completes. If it devotes a thread to each in-flight request, then as the number of concurrent requests rises it will run out of memory or other thread-related resource before it runs out of sockets. It avoids the need for threads by using asynchronous I/O.

这一章我们将实现一个简单的网络爬虫。这个爬虫只是一个原型式的异步应用,因为它等待许多响应而只做少量的计算。一次爬的网页越多,它就能越快的完成任务。如果它为每个动态的请求启动一个线程的话,随着并发请求数量的增加,它会在耗尽套接字之前,耗尽内存或者线程相关的资源。使用异步 I/O 可以避免这个的问题。

We present the example in three stages. First, we show an async event loop and sketch a crawler that uses the event loop with callbacks: it is very efficient, but extending it to more complex problems would lead to unmanageable spaghetti code. Second, therefore, we show that Python coroutines are both efficient and extensible. We implement simple coroutines in Python using generator functions. In the third stage, we use the full-featured coroutines from Python’s standard “asyncio” library[^16], and coordinate them using an async queue.

我们将分三个阶段展示这个例子。

- 首先,我们会实现一个异步事件循环并用这个事件循环和回调来勾画出一只网络爬虫。它很有效,但是当把它扩展成更复杂的问题时,就会导致无法管理的混乱代码。

- 然后,由于 Python 的协程不仅有效而且可扩展,我们将用 Python 的生成器函数实现一个简单的协程。

- 在最后一个阶段,我们将使用 Python 标准库 “asyncio” 中功能完整的协程, 并通过异步队列完成这个网络爬虫。(在 PyCon 2013 上,Guido 介绍了标准的 asyncio 库,当时称之为“Tulip”。)

The Task 任务

A web crawler finds and downloads all pages on a website, perhaps to archive or index them. Beginning with a root URL, it fetches each page, parses it for links to unseen pages, and adds these to a queue. It stops when it fetches a page with no unseen links and the queue is empty.

网络爬虫寻找并下载一个网站上的所有网页,也许还会把它们存档,为它们建立索引。从根 URL 开始,它获取每个网页,解析出没有遇到过的链接加到队列中。当网页没有未见到过的链接并且队列为空时,它便停止运行。

We can hasten this process by downloading many pages concurrently. As the crawler finds new links, it launches simultaneous fetch operations for the new pages on separate sockets. It parses responses as they arrive, adding new links to the queue. There may come some point of diminishing returns where too much concurrency degrades performance, so we cap the number of concurrent requests, and leave the remaining links in the queue until some in-flight requests complete.

我们可以通过同时下载大量的网页来加快这一过程。当爬虫发现新的链接,它使用一个新的套接字并行的处理这个新链接,解析响应,添加新链接到队列。当并发很大时,可能会导致性能下降,所以我们会限制并发的数量,在队列保留那些未处理的链接,直到一些正在执行的任务完成。

The Traditional Approach 传统方式

How do we make the crawler concurrent? Traditionally we would create a thread pool. Each thread would be in charge of downloading one page at a time over a socket. For example, to download a page from xkcd.com:

怎么使一个爬虫并发?传统的做法是创建一个线程池,每个线程使用一个套接字在一段时间内负责一个网页的下载。比如,下载 xkcd.com 网站的一个网页:

def fetch(url):sock = socket.socket()sock.connect(('xkcd.com', 80))request = 'GET {} HTTP/1.0\r\nHost: xkcd.com\r\n\r\n'.format(url)sock.send(request.encode('ascii'))response = b''chunk = sock.recv(4096)while chunk:response += chunkchunk = sock.recv(4096)# Page is now downloaded.links = parse_links(response)q.add(links)

By default, socket operations are blocking: when the thread calls a method like connect or recv, it pauses until the operation completes.1 Consequently to download many pages at once, we need many threads. A sophisticated application amortizes the cost of thread-creation by keeping idle threads in a thread pool, then checking them out to reuse them for subsequent tasks; it does the same with sockets in a connection pool.

套接字操作默认是阻塞的:当一个线程调用一个类似 connect 和 recv 方法时,它会阻塞,直到操作完成。(即使是 send 也能被阻塞,比如接收端在接受外发消息时缓慢而系统的外发数据缓存已经满了的情况下)因此,为了同一时间内下载多个网页,我们需要很多线程。一个复杂的应用会通过线程池保持空闲的线程来分摊创建线程的开销。同样的做法也适用于套接字,使用连接池。

And yet, threads are expensive, and operating systems enforce a variety of hard caps on the number of threads a process, user, or machine may have. On Jesse’s system, a Python thread costs around 50k of memory, and starting tens of thousands of threads causes failures. If we scale up to tens of thousands of simultaneous operations on concurrent sockets, we run out of threads before we run out of sockets. Per-thread overhead or system limits on threads are the bottleneck.

到目前为止,使用线程的是成本昂贵的,操作系统对一个进程、一个用户、一台机器能使用线程做了不同的硬性限制。在 作者 Jesse 的系统中,一个 Python 线程需要 50K 的内存,开启上万个线程就会失败。每个线程的开销和系统的限制就是这种方式的瓶颈所在。

In his influential article “The C10K problem”2, Dan Kegel outlines the limitations of multithreading for I/O concurrency. He begins,

在 Dan Kegel 那一篇很有影响力的文章“The C10K problem”中,它提出了多线程方式在 I/O 并发上的局限性。他在开始写道,

- It’s time for web servers to handle ten thousand clients simultaneously, don’t you think? After all, the web is a big place now.

- 网络服务器到了要同时处理成千上万的客户的时代了,你不这样认为么?毕竟,现在网络规模很大了。

Kegel coined the term “C10K” in 1999. Ten thousand connections sounds dainty now, but the problem has changed only in size, not in kind. Back then, using a thread per connection for C10K was impractical. Now the cap is orders of magnitude higher. Indeed, our toy web crawler would work just fine with threads. Yet for very large scale applications, with hundreds of thousands of connections, the cap remains: there is a limit beyond which most systems can still create sockets, but have run out of threads. How can we overcome this?

Kegel 在 1999 年创造出“C10K”这个术语。一万个连接在今天看来还是可接受的,但是问题依然存在,只不过大小不同。回到那时候,对于 C10K 问题,每个连接启一个线程是不切实际的。现在这个限制已经成指数级增长。确实,我们的玩具网络爬虫使用线程也可以工作的很好。但是,对于有着千万级连接的大规模应用来说,限制依然存在:它会消耗掉所有线程,即使套接字还够用。那么我们该如何解决这个问题?

Async 异步

Asynchronous I/O frameworks do concurrent operations on a single thread using

异步 I/O 框架在一个线程中完成并发操作。让我们看看这是怎么做到的。

non-blocking sockets. In our async crawler, we set the socket non-blocking

before we begin to connect to the server:

异步框架使用非阻塞套接字。异步爬虫中,我们在发起到服务器的连接前把套接字设为非阻塞:

sock = socket.socket()sock.setblocking(False) # 设置socket非阻塞,默认是阻塞try:sock.connect(('xkcd.com', 80))except BlockingIOError:pass

Irritatingly, a non-blocking socket throws an exception from connect, even when it is working normally. This exception replicates the irritating behavior of the underlying C function, which sets errno to EINPROGRESS to tell you it has begun.

恼人的是,对一个非阻塞套接字调用 connect 方法会立即抛出异常,即使它可以正常工作。这个异常复现了底层 C 语言函数令人厌烦的行为,它把 errno 设置为 EINPROGRESS,告诉你操作已经开始。

Now our crawler needs a way to know when the connection is established, so it can send the HTTP request. We could simply keep trying in a tight loop:

现在我们的爬虫需要一种知道连接何时建立的方法,这样它才能发送 HTTP 请求。我们可以简单地使用循环来重试:

request = 'GET {} HTTP/1.0\r\nHost: xkcd.com\r\n\r\n'.format(url)encoded = request.encode('ascii')while True:try:sock.send(encoded)break # Done.except OSError as e:passprint('sent')

This method not only wastes electricity, but it cannot efficiently await events on multiple sockets. In ancient times, BSD Unix’s solution to this problem was select, a C function that waits for an event to occur on a non-blocking socket or a small array of them. Nowadays the demand for Internet applications with huge numbers of connections has led to replacements like poll, then kqueue on BSD and epollon Linux. These APIs are similar to select, but perform well with very large numbers of connections.

这种方法不仅消耗 CPU,也不能有效的等待多个套接字。在远古时代,BSD Unix 的解决方法是 select,这是一个 C 函数,它在一个或一组非阻塞套接字上等待事件发生。现在,互联网应用大量连接的需求,导致 select 被 poll 所代替,在 BSD 上的实现是 kqueue ,在 Linux 上是 epoll。它们的 API 和 select 相似,但在大数量的连接中也能有较好的性能。

Python 3.4’s DefaultSelector uses the best select-like function available on your system. To register for notifications about network I/O, we create a non-blocking socket and register it with the default selector:

Python 3.4 的 DefaultSelector 会使用你系统上最好的 select 类函数。要注册一个网络 I/O 事件的提醒,我们会创建一个非阻塞套接字,并使用默认 selector 注册它。

from selectors import DefaultSelector, EVENT_WRITEselector = DefaultSelector()sock = socket.socket()sock.setblocking(False) # 设置非阻塞try:sock.connect(('xkcd.com', 80))except BlockingIOError:passdef connected():selector.unregister(sock.fileno())print('connected!')selector.register(sock.fileno(), EVENT_WRITE, connected)

We disregard the spurious error and call selector.register, passing in the socket’s file descriptor and a constant that expresses what event we are waiting for. To be notified when the connection is established, we pass EVENT_WRITE: that is, we want to know when the socket is “writable”. We also pass a Python function, connected, to run when that event occurs. Such a function is known as a callback.

我们不理会这个伪造的错误,调用 selector.register,传递套接字文件描述符和一个表示我们想要监听什么事件的常量表达式。为了当连接建立时收到提醒,我们使用 EVENT_WRITE :它表示什么时候这个套接字可写。我们还传递了一个 Python 函数 connected,当对应事件发生时被调用。这样的函数被称为回调。

We process I/O notifications as the selector receives them, in a loop:

在一个循环中,selector 接收到 I/O 提醒时我们处理它们:

def loop():while True:events = selector.select()for event_key, event_mask in events:callback = event_key.datacallback()

The connected callback is stored as event_key.data, which we retrieve and execute once the non-blocking socket is connected.

connected 回调函数被保存在 event_key.data 中,一旦这个非阻塞套接字建立连接,它就会被取出来执行

Unlike in our fast-spinning loop above, the call to select here pauses, awaiting the next I/O events. Then the loop runs callbacks that are waiting for these events. Operations that have not completed remain pending until some future tick of the event loop.

不像我们前面那个快速轮转的循环,这里的 select 调用会暂停,等待下一个 I/O 事件,接着执行等待这些事件的回调函数。没有完成的操作会保持挂起,直到进到下一个事件循环时执行。

What have we demonstrated already? We showed how to begin an operation and execute a callback when the operation is ready. An async framework builds on the two features we have shown—non-blocking sockets and the event loop—to run concurrent operations on a single thread.

到目前为止我们展现了什么?我们展示了如何开始一个 I/O 操作和当操作准备好时调用回调函数。异步框架,它在单线程中执行并发操作,其建立在两个功能之上,非阻塞套接字和事件循环。

We have achieved “concurrency” here, but not what is traditionally called “parallelism”. That is, we built a tiny system that does overlapping I/O. It is capable of beginning new operations while others are in flight. It does not actually utilize multiple cores to execute computation in parallel. But then, this system is designed for I/O-bound problems, not CPU-bound ones.3

我们这里达成了“并发性concurrency”,但不是传统意义上的“并行性parallelism”。也就是说,我们构建了一个可以进行重叠 I/O 的微小系统,它可以在其它操作还在进行的时候就开始一个新的操作。它实际上并没有利用多核来并行执行计算。这个系统是用于解决 I/O 密集I/O-bound问题的,而不是解决 CPU 密集CPU-bound问题的。(Python 的全局解释器锁禁止在一个进程中以任何方式并行执行 Python 代码。在 Python 中并行化 CPU 密集的算法需要多个进程,或者以将该代码移植为 C 语言并行版本。但是这是另外一个话题了。)

So our event loop is efficient at concurrent I/O because it does not devote thread resources to each connection. But before we proceed, it is important to correct a common misapprehension that async is faster than multithreading. Often it is not—indeed, in Python, an event loop like ours is moderately slower than multithreading at serving a small number of very active connections. In a runtime without a global interpreter lock, threads would perform even better on such a workload. What asynchronous I/O is right for, is applications with many slow or sleepy connections with infrequent events.[^11][^bayer]

所以,我们的事件循环在并发 I/O 上是有效的,因为它并不用为每个连接拨付线程资源。

但是在我们开始前,我们需要澄清一个常见的误解:异步比多线程快。通常并不是这样的,事实上,在 Python 中,在处理少量非常活跃的连接时,像我们这样的事件循环是慢于多线程的。在没有全局解释器锁的运行时环境中,在同样的负载下线程会执行的更好。异步 I/O 真正适用于事件很少、有许多缓慢或睡眠的连接的应用程序。(Jesse 在“什么是异步,它如何工作,什么时候该用它?”一文中指出了异步所适用和不适用的场景。Mike Bayer 在“异步 Python 和数据库”一文中比较了不同负载情况下异步 I/O 和多线程的不同。)

Programming With Callbacks 回调

With the runty async framework we have built so far, how can we build a web crawler? Even a simple URL-fetcher is painful to write.

用我们刚刚建立的异步框架,怎么才能完成一个网络爬虫?即使是一个简单的网页下载程序也是很难写的。

We begin with global sets of the URLs we have yet to fetch, and the URLs we have seen:

首先,我们有一个尚未获取的 URL 集合,和一个已经解析过的 URL 集合:

urls_todo = set(['/'])seen_urls = set(['/'])

The seen_urls set includes urls_todo plus completed URLs. The two sets are initialized with the root URL “/”.

seen_urls 集合包括 urls_todo 和已经完成的 URL。用根 URL / 初始化它们。

Fetching a page will require a series of callbacks. The connected callback fires when a socket is connected, and sends a GET request to the server. But then it must await a response, so it registers another callback. If, when that callback fires, it cannot read the full response yet, it registers again, and so on.

获取一个网页需要一系列的回调。在套接字连接建立时会触发 connected 回调,它向服务器发送一个 GET 请求。但是它要等待响应,所以我们需要注册另一个回调函数;当该回调被调用,它仍然不能读取到完整的请求时,就会再一次注册回调,如此反复。

Let us collect these callbacks into a Fetcher object. It needs a URL, a socket object, and a place to accumulate the response bytes:

让我们把这些回调放在一个 Fetcher 对象中,它需要一个 URL,一个套接字,还需要一个地方保存返回的字节:

class Fetcher:def __init__(self, url):self.response = b'' # Empty array of bytes.self.url = urlself.sock = None

We begin by calling Fetcher.fetch:

我们的入口点在 Fetcher.fetch:

# Method on Fetcher class.def fetch(self):self.sock = socket.socket()self.sock.setblocking(False) # 设置非阻塞try:self.sock.connect(('xkcd.com', 80))except BlockingIOError:pass# Register next callback.selector.register(self.sock.fileno(),EVENT_WRITE,self.connected)

The fetch method begins connecting a socket. But notice the method returns before the connection is established. It must return control to the event loop to wait for the connection. To understand why, imagine our whole application was structured so:

fetch 方法从连接一个套接字开始。但是要注意这个方法在连接建立前就返回了。它必须将控制返回到事件循环中等待连接建立。为了理解为什么要这样做,假设我们程序的整体结构如下

# Begin fetching http://xkcd.com/353/fetcher = Fetcher('/353/')fetcher.fetch()while True:events = selector.select() # 阻塞for event_key, event_mask in events:callback = event_key.datacallback(event_key, event_mask)

All event notifications are processed in the event loop when it calls select. Hence fetch must hand control to the event loop, so that the program knows when the socket has connected. Only then does the loop run the connected callback, which was registered at the end of fetch above.

当调用 select 函数后,所有的事件提醒才会在事件循环中处理,所以 fetch 必须把控制权交给事件循环,这样我们的程序才能知道什么时候连接已建立,接着循环调用 connected 回调,它已经在上面的 fetch 方法中注册过。

Here is the implementation of connected:

这里是我们的 connected 方法的实现:

# Method on Fetcher class.def connected(self, key, mask):print('connected!')selector.unregister(key.fd)request = 'GET {} HTTP/1.0\r\nHost: xkcd.com\r\n\r\n'.format(self.url)self.sock.send(request.encode('ascii'))# Register the next callback.selector.register(key.fd,EVENT_READ,self.read_response) # 注册响应的的可读事件,与响应处理回调函数

The method sends a GET request. A real application would check the return value of send in case the whole message cannot be sent at once. But our request is small and our application unsophisticated. It blithely calls send, then waits for a response. Of course, it must register yet another callback and relinquish control to the event loop. The next and final callback, read_response, processes the server’s reply:

这个方法发送一个 GET 请求。一个真正的应用会检查 send 的返回值,以防所有的信息没能一次发送出去。但是我们的请求很小,应用也不复杂。它只是简单的调用 send,然后等待响应。当然,它必须注册另一个回调并把控制权交给事件循环。接下来也是最后一个回调函数 read_response,它处理服务器的响应:

# Method on Fetcher class.def read_response(self, key, mask):global stoppedchunk = self.sock.recv(4096) # 4k chunk size.if chunk:self.response += chunkelse:selector.unregister(key.fd) # Done reading.links = self.parse_links()# Python set-logic:for link in links.difference(seen_urls):urls_todo.add(link)Fetcher(link).fetch() # <- New Fetcher.seen_urls.update(links)urls_todo.remove(self.url)if not urls_todo:stopped = True # urls_todo 爬取集合没有任务时,stopped=True,将停止循环

The callback is executed each time the selector sees that the socket is “readable”, which could mean two things: the socket has data or it is closed.

这个回调在每次 selector 发现套接字可读时被调用,可读有两种情况:

- 套接字接受到数据(可读)

- 或者它被关闭。

The callback asks for up to four kilobytes of data from the socket. If less is ready, chunk contains whatever data is available. If there is more, chunk is four kilobytes long and the socket remains readable, so the event loop runs this callback again on the next tick. When the response is complete, the server has closed the socket and chunk is empty.

这个回调函数从套接字读取 4K 数据。如果不到 4k,那么有多少读多少。如果比 4K 多,chunk 中只包 4K 数据并且这个套接字保持可读,这样在事件循环的下一个周期,会再次回到这个回调函数。当响应完成时,服务器关闭这个套接字,chunk 为空。

The parse_links method, not shown, returns a set of URLs. We start a new fetcher for each new URL, with no concurrency cap. Note a nice feature of async programming with callbacks: we need no mutex around changes to shared data, such as when we add links to seen_urls. There is no preemptive multitasking, so we cannot be interrupted at arbitrary points in our code.

这里没有展示的 parse_links 方法,它返回一个 URL 集合。我们为每个新的 URL 启动一个 fetcher。注意一个使用异步回调方式编程的好处:我们不需要为共享数据加锁,比如我们往 seen_urls 增加新链接时。这是一种非抢占式的多任务,它不会在我们代码中的任意一个地方被打断。

We add a global stopped variable and use it to control the loop:

我们增加了一个全局变量 stopped,用它来控制这个循环:

stopped = Falsedef loop():while not stopped: # stopped 控制循环events = selector.select() # 阻塞for event_key, event_mask in events:callback = event_key.datacallback()

Once all pages are downloaded the fetcher stops the global event loop and the program exits.

一旦所有的网页被下载下来,fetcher 停止这个事件循环,程序退出。

This example makes async’s problem plain: spaghetti code. We need some way to express a series of computations and I/O operations, and schedule multiple such series of operations to run concurrently. But without threads, a series of operations cannot be collected into a single function: whenever a function begins an I/O operation, it explicitly saves whatever state will be needed in the future, then returns. You are responsible for thinking about and writing this state-saving code.

这个例子让异步编程的一个问题明显的暴露出来:意大利面代码。我们需要某种方式来表达一系列的计算和 I/O 操作,并且能够调度多个这样的系列操作让它们并发的执行。但是,没有线程你不能把这一系列操作写在一个函数中:当函数开始一个 I/O 操作,它明确的把未来所需的状态保存下来,然后返回。你需要考虑如何写这个状态保存的代码。

Let us explain what we mean by that. Consider how simply we fetched a URL on a thread with a conventional blocking socket:

让我们来解释下这到底是什么意思。先来看一下在线程中使用通常的阻塞套接字来获取一个网页时是多么简单:

# Blocking version. 阻塞版本,同步思想def fetch(url):sock = socket.socket()sock.connect(('xkcd.com', 80))request = 'GET {} HTTP/1.0\r\nHost: xkcd.com\r\n\r\n'.format(url)sock.send(request.encode('ascii'))response = b''chunk = sock.recv(4096)while chunk:response += chunkchunk = sock.recv(4096)# Page is now downloaded.links = parse_links(response)q.add(links)

What state does this function remember between one socket operation and the next? It has the socket, a URL, and the accumulating response. A function that runs on a thread uses basic features of the programming language to store this temporary state in local variables, on its stack. The function also has a “continuation”—that is, the code it plans to execute after I/O completes. The runtime remembers the continuation by storing the thread’s instruction pointer. You need not think about restoring these local variables and the continuation after I/O. It is built in to the language.

在一个套接字操作和下一个操作之间这个函数到底记住了什么状态?它有一个套接字,一个 URL 和一个可增长的 response。运行在线程中的函数使用编程语言的基本功能来在栈中的局部变量保存这些临时状态。这样的函数也有一个“continuation”——它会在 I/O 结束后执行这些代码。运行时环境通过线程的指令指针来记住这个 continuation。你不必考虑怎么在 I/O 操作后恢复局部变量和这个 continuation。语言本身的特性帮你解决。

But with a callback-based async framework, these language features are no help. While waiting for I/O, a function must save its state explicitly, because the function returns and loses its stack frame before I/O completes. In lieu of local variables, our callback-based example stores sock and response as attributes of self, the Fetcher instance. In lieu of the instruction pointer, it stores its continuation by registering the callbacks connected and read_response. As the application’s features grow, so does the complexity of the state we manually save across callbacks. Such onerous bookkeeping makes the coder prone to migraines.

但是用一个基于回调的异步框架时,这些语言特性不能提供一点帮助。当等待 I/O 操作时,一个函数必须明确的保存它的状态,因为它会在 I/O 操作完成之前返回并清除栈帧。在我们基于回调的例子中,作为局部变量的替代,我们把 sock 和 response 作为 Fetcher 实例 self 的属性来存储。而作为指令指针的替代,它通过注册 connected 和 read_response 回调来保存它的 continuation。随着应用功能的增长,我们需要手动保存的回调的复杂性也会增加。如此繁复的记账式工作会让编码者感到头痛。

Even worse, what happens if a callback throws an exception, before it schedules the next callback in the chain? Say we did a poor job on the parse_links method and it throws an exception parsing some HTML:

更糟糕的是,当我们的回调函数抛出异常会发生什么?假设我们没有写好 parse_links 方法,它在解析 HTML 时抛出异常:

Traceback (most recent call last):File "loop-with-callbacks.py", line 111, in <module>loop()File "loop-with-callbacks.py", line 106, in loopcallback(event_key, event_mask)File "loop-with-callbacks.py", line 51, in read_responselinks = self.parse_links()File "loop-with-callbacks.py", line 67, in parse_linksraise Exception('parse error')Exception: parse error

The stack trace shows only that the event loop was running a callback. We do not remember what led to the error. The chain is broken on both ends: we forgot where we were going and whence we came. This loss of context is called “stack ripping”, and in many cases it confounds the investigator. Stack ripping also prevents us from installing an exception handler for a chain of callbacks, the way a “try / except” block wraps a function call and its tree of descendents.4

这个堆栈回溯只能显示出事件循环调用了一个回调。我们不知道是什么导致了这个错误。这条链的两边都被破坏:不知道从哪来也不知到哪去。这种丢失上下文的现象被称为“堆栈撕裂stack ripping”,经常会导致无法分析原因。它还会阻止我们为回调链设置异常处理,即那种用“try / except”块封装函数调用及其调用树。(对于这个问题的更复杂的解决方案,参见 http://www.tornadoweb.org/en/stable/stack_context.html )

So, even apart from the long debate about the relative efficiencies of multithreading and async, there is this other debate regarding which is more error-prone: threads are susceptible to data races if you make a mistake synchronizing them, but callbacks are stubborn to debug due to stack ripping.

所以,除了关于多线程和异步哪个更高效的长期争议之外,还有一个关于这两者之间的争论:谁更容易跪了。

- 如果在同步上出现失误,线程更容易出现数据竞争的问题,

- 而回调因为“堆栈撕裂stack ripping“问题而非常难于调试。

Coroutines 协程

We entice you with a promise. It is possible to write asynchronous code that combines the efficiency of callbacks with the classic good looks of multithreaded programming. This combination is achieved with a pattern called “coroutines”. Using Python 3.4’s standard asyncio library, and a package called “aiohttp”, fetching a URL in a coroutine is very direct5:

我们用一个承诺诱惑你。可以编写异步代码,将回调的效率与多线程编程的经典好看结合起来。 这种组合通过称为“协程”的模式来实现。 使用Python 3.4的标准asyncio库和一个名为“aiohttp”的包,在协程中获取一个URL是非常直接的[^ 10]:

@asyncio.coroutinedef fetch(self, url):response = yield from self.session.get(url)body = yield from response.read()

It is also scalable. Compared to the 50k of memory per thread and the operating system’s hard limits on threads, a Python coroutine takes barely 3k of memory on Jesse’s system. Python can easily start hundreds of thousands of coroutines.

它也是可扩展的。与每个线程的50k内存和操作系统对线程的硬限制相比,Python协程在Jesse系统上只需要3k的内存。Python可以轻松启动数十万个协程。

The concept of a coroutine, dating to the elder days of computer science, is simple: it is a subroutine that can be paused and resumed. Whereas threads are preemptively multitasked by the operating system, coroutines multitask cooperatively: they choose when to pause, and which coroutine to run next.

协程的概念,可以追溯到计算机科学的祖先,很简单:它是一个可以暂停和恢复的子程序。而线程是由操作系统抢占式多任务,协同多任务协作:他们选择何时暂停,以及哪个协程运行下一步。

There are many implementations of coroutines; even in Python there are several. The coroutines in the standard “asyncio” library in Python 3.4 are built upon generators, a Future class, and the “yield from” statement. Starting in Python 3.5, coroutines are a native feature of the language itself6; however, understanding coroutines as they were first implemented in Python 3.4, using pre-existing language facilities, is the foundation to tackle Python 3.5’s native coroutines.

有很多协同的实现; 即使在Python也有几个。

Python 3.4中的标准“asyncio”库中的协程是基于generator,Future类和“yield from”语句构建的。

从Python 3.5开始,协程是语言本身的一个本地特性[^ 17]; 然而,了解协同程序,因为他们第一次在Python 3.4中实现,使用预先存在的语言设施,是解决Python 3.5的本地协同程序的基础。

To explain Python 3.4’s generator-based coroutines, we will engage in an exposition of generators and how they are used as coroutines in asyncio, and trust you will enjoy reading it as much as we enjoyed writing it. Once we have explained generator-based coroutines, we shall use them in our async web crawler.

为了解释Python 3.4的基于生成器的协程,我们将介绍一些生成器,以及它们如何在asyncio中用作协同程序,并且相信你会喜欢阅读它,就像我们喜欢写它一样。一旦我们解释了基于生成器的协同程序,我们将使用它们在我们的异步Web爬虫。

How Python Generators Work 生成器如何工作

Before you grasp Python generators, you have to understand how regular Python functions work. Normally, when a Python function calls a subroutine, the subroutine retains control until it returns, or throws an exception. Then control returns to the caller:

在掌握 Python 生成器之前,您必须了解常规 Python 函数的工作原理。通常,当 Python 函数调用子例程时,子例程保留控制权,直到返回或抛出异常。然后控制权返回给调用者:

>>> def foo():... bar()...>>> def bar():... pass

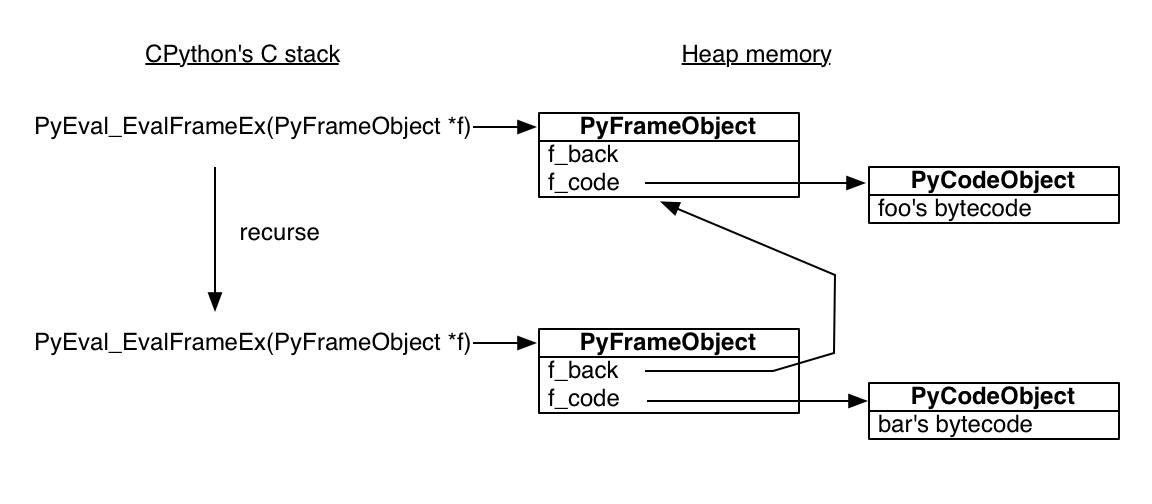

The standard Python interpreter is written in C. The C function that executes a Python function is called, mellifluously, PyEval_EvalFrameEx. It takes a Python stack frame object and evaluates Python bytecode in the context of the frame. Here is the bytecode for foo:

标准的 Python 解释器是用 C 编写的。执行Python函数的C函数被称为 PyEval_EvalFrameEx。它需要一个 Python 栈框架对象,并在框架的上下文中评估 Python 字节码。这里是 foo 的字节码:

>>> import dis>>> dis.dis(foo)2 0 LOAD_GLOBAL 0 (bar)3 CALL_FUNCTION 0 (0 positional, 0 keyword pair)6 POP_TOP7 LOAD_CONST 0 (None)10 RETURN_VALUE

The foo function loads bar onto its stack and calls it, then pops its return value from the stack, loads None onto the stack, and returns None.foo 函数将 bar 加载到它的堆栈上并调用它,然后从堆栈中弹出其返回值,将 None加载到堆栈中,并返回 None。

When PyEval_EvalFrameEx encounters the CALL_FUNCTION bytecode, it creates a new Python stack frame and recurses: that is, it calls PyEval_EvalFrameExrecursively with the new frame, which is used to execute bar.

当 PyEval_EvalFrameEx 遇到 CALL_FUNCTION 字节码时,它创建一个新的 Python 栈框架和递归:也就是说,它用新的框架递归调用 PyEval_EvalFrameEx,用来执行 bar。

It is crucial to understand that Python stack frames are allocated in heap memory! The Python interpreter is a normal C program, so its stack frames are normal stack frames. But the Python stack frames it manipulates are on the heap. Among other surprises, this means a Python stack frame can outlive its function call. To see this interactively, save the current frame from within bar:

了解Python堆栈在堆内存中分配是至关重要的!Python 解释器是一个正常的 C 程序,所以它的栈帧是正常的栈帧。 但是 Python 栈帧操作是在堆上。其他令人惊奇的是,这意味着 Python 栈帧比其函数调用存在更久。为了看到交互效果,在bar中保存当前栈帧:

>>> import inspect>>> frame = None>>> def foo():... bar()...>>> def bar():... global frame... frame = inspect.currentframe()...>>> foo()>>> # The frame was executing the code for 'bar'.>>> frame.f_code.co_name'bar'>>> # Its back pointer refers to the frame for 'foo'.>>> caller_frame = frame.f_back>>> caller_frame.f_code.co_name'foo'

The stage is now set for Python generators, which use the same building blocks—code objects and stack frames—to marvelous effect.

该阶段现在设置为Python生成器,它使用相同的构建块—代码对象和栈帧—以达到奇妙的效果。

This is a generator function:

这是一个生成器函数:

>>> def gen_fn():... result = yield 1 # 生成器函数... print('result of yield: {}'.format(result))... result2 = yield 2... print('result of 2nd yield: {}'.format(result2))... return 'done'...

When Python compiles gen_fn to bytecode, it sees the yield statement and knows that gen_fn is a generator function, not a regular one. It sets a flag to remember this fact:

当 Python 将 gen_fn 编译成字节码时,它看到了 yield 语句并且知道 gen_fn 是一个生成器函数,而不是一个常规函数。它设置一个标志,以记住这个事实:

>>> # The generator flag is bit position 5.>>> generator_bit = 1 << 5>>> bool(gen_fn.__code__.co_flags & generator_bit)True

When you call a generator function, Python sees the generator flag, and it does not actually run the function. Instead, it creates a generator:

当你调用一个生成器函数, Python 看到生成器标志,它实际上不运行该函数。相反,它创建一个生成器:

>>> gen = gen_fn()>>> type(gen)<class 'generator'>

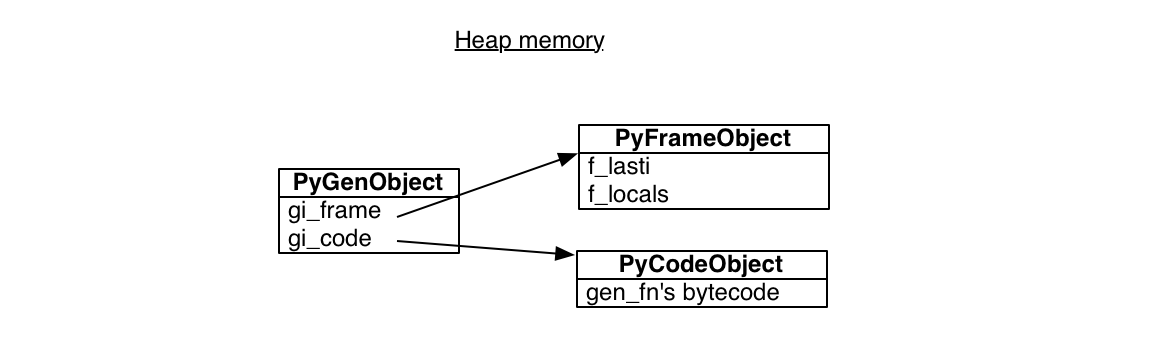

A Python generator encapsulates a stack frame plus a reference to some code, the body of gen_fn:

一个栈帧加上一些代码的引用,gen_fn 的主体:

>>> gen.gi_code.co_name'gen_fn'

All generators from calls to gen_fn point to this same code. But each has its own stack frame. This stack frame is not on any actual stack, it sits in heap memory waiting to be used:

来自 gen_fn 调用的所有生成器都指向这个相同的代码。但每个都有自己的栈帧。这个栈帧不在任何真实的栈中,它是在堆内存分配并等待被使用:

The frame has a “last instruction” pointer, the instruction it executed most recently. In the beginning, the last instruction pointer is -1, meaning the generator has not begun:

该帧具有“最后指令”指针,它是最近执行的指令。开始时,最后一个指令指针是-1,表示生成器尚未开始:

>>> gen.gi_frame.f_lasti-1

When we call send, the generator reaches its first yield, and pauses. The return value of send is 1, since that is what gen passes to the yield expression:

当我们调用 send 时,生成器到达它的第一个 yield,并暂停。send 的返回值是1,因为这是 gen 传递给 yield 表达式:

>>> gen.send(None)1

The generator’s instruction pointer is now 3 bytecodes from the start, part way through the 56 bytes of compiled Python:

生成器的指令指针现在是3个字节码,部分通过编译的 Python 的56个字节:

>>> gen.gi_frame.f_lasti3>>> len(gen.gi_code.co_code)56

The generator can be resumed at any time, from any function, because its stack frame is not actually on the stack: it is on the heap. Its position in the call hierarchy is not fixed, and it need not obey the first-in, last-out order of execution that regular functions do. It is liberated, floating free like a cloud.

生成器可以在任何时候从任何函数恢复,因为它的栈帧实际上不在栈上:在堆上。它在调用层次结构中的位置不是固定的,并且它不需要遵守常规函数执行的先进先出顺序。它是解放的,像自由浮动的云一样。

We can send the value “hello” into the generator and it becomes the result of the yield expression, and the generator continues until it yields 2:

我们可以发送值“hello”到生成器,它成为 yield 表达式的结果,生成器继续,直到它产生2:

>>> gen.send('hello')result of yield: hello2

Its stack frame now contains the local variable result:

它的堆栈帧现在包含局部变量 result:

>>> gen.gi_frame.f_locals{'result': 'hello'}

Other generators created from gen_fn will have their own stack frames and local variables.

从 gen_fn 创建的其他生成器将有自己的栈帧和局部变量。

When we call send again, the generator continues from its second yield, and finishes by raising the special StopIteration exception:

当我们再次调用 send 时,生成器从它的第二个 yield 继续,并通过生成特殊的 StopIteration 异常来结束:

>>> gen.send('goodbye')result of 2nd yield: goodbyeTraceback (most recent call last):File "<input>", line 1, in <module>StopIteration: done

The exception has a value, which is the return value of the generator: the string "done".

异常有一个值,它是生成器的返回值:字符串"done"。

Building Coroutines With Generators 构造带有生成器的协程

So a generator can pause, and it can be resumed with a value, and it has a return value. Sounds like a good primitive upon which to build an async programming model, without spaghetti callbacks! We want to build a “coroutine”: a routine that is cooperatively scheduled with other routines in the program. Our coroutines will be a simplified version of those in Python’s standard “asyncio” library. As in asyncio, we will use generators, futures, and the “yield from” statement.

因此,生成器可以暂停,并且可以使用值恢复,并且它具有返回值。听起来像一个很好的原生的构建异步编程模型方法,没有意大利面条式的回调!我们想建立一个“协程”:一个与程序中的其他程序计划合作的程序。我们的协程将是Python标准“asyncio”库中的简化版本。 在 asyncio 中,我们将使用 generator,futures 和“yield from”语句。

First we need a way to represent some future result that a coroutine is waiting for. A stripped-down version:

首先,我们需要一种方法来表示协程正在等待的 future 结果。 简单的版本:

class Future:def __init__(self):self.result = Noneself._callbacks = []def add_done_callback(self, fn):self._callbacks.append(fn)def set_result(self, result):self.result = resultfor fn in self._callbacks:fn(self)

A future is initially “pending”. It is “resolved” by a call to set_result.7

future 初始化是“等待的”。它通过调用 set_result来“执行完成“。7

Let us adapt our fetcher to use futures and coroutines. We wrote fetch with a callback:

让我们用 futures 和协程来适配我们的 fetcher 函数。 我们用一个回调来写 fetch:

class Fetcher:def fetch(self):self.sock = socket.socket()self.sock.setblocking(False)try:self.sock.connect(('xkcd.com', 80))except BlockingIOError:passselector.register(self.sock.fileno(),EVENT_WRITE,self.connected)def connected(self, key, mask):print('connected!')# And so on....

The fetch method begins connecting a socket, then registers the callback, connected, to be executed when the socket is ready. Now we can combine these two steps into one coroutine:fetch方法通过连接一个socket开始,之后注册一个回调函数,connected,用来在socket准备好的时候执行。现在我们可以融合这两步在一个协程:

def fetch(self):sock = socket.socket()sock.setblocking(False)try:sock.connect(('xkcd.com', 80))except BlockingIOError:passf = Future()def on_connected():f.set_result(None)selector.register(sock.fileno(),EVENT_WRITE,on_connected)yield fselector.unregister(sock.fileno())print('connected!')

Now fetch is a generator function, rather than a regular one, because it contains a yield statement. We create a pending future, then yield it to pause fetch until the socket is ready. The inner function on_connected resolves the future.

当前的 fetch 是一个生成器函数,而不是一个普通函数,因为它包含一个 yield 关键字。我们创建一个挂起的future,然后通过 yield 暂停 fetch 直到socket准备好。内部函数on_connected来调用feture的方法。

But when the future resolves, what resumes the generator? We need a coroutine driver. Let us call it “task”:

但是,当future执行完,用什么来恢复生成器?我们需要一个协程 driver。让我们称它为“任务”:

class Task:def __init__(self, coro):self.coro = corof = Future()f.set_result(None)self.step(f)def step(self, future):try:next_future = self.coro.send(future.result)except StopIteration:returnnext_future.add_done_callback(self.step)# Begin fetching http://xkcd.com/353/fetcher = Fetcher('/353/')Task(fetcher.fetch())loop()

The task starts the fetch generator by sending None into it. Then fetch runs until it yields a future, which the task captures as next_future. When the socket is connected, the event loop runs the callback on_connected, which resolves the future, which calls step, which resumes fetch.

任务启动 fetch 通过发送 None 给它。 然后 fetch 运行直到它生成一个future,任务捕获为 next_future。当socket连接的时候,事件循环运行回调函数on_connected,它调用future,future执行 step, 从而恢复生成器 fetch。

Factoring Coroutines With yield from 通过 yield from 串联多个协程

Once the socket is connected, we send the HTTP GET request and read the server response. These steps need no longer be scattered among callbacks; we gather them into the same generator function:

一旦socket连接,我们发送 HTTP GET 请求并且读取服务器响应。这些步骤不再分发到回调中,我们将他们收集在同一个生成器函数中。

def fetch(self):# ... connection logic from above, then:sock.send(request.encode('ascii'))while True:f = Future()def on_readable():f.set_result(sock.recv(4096))selector.register(sock.fileno(),EVENT_READ,on_readable)chunk = yield fselector.unregister(sock.fileno())if chunk:self.response += chunkelse:# Done reading.break

This code, which reads a whole message from a socket, seems generally useful. How can we factor it from fetch into a subroutine? Now Python 3’s celebrated yield from takes the stage. It lets one generator delegate to another.

这段代码从一个socket中读取了整个信息,看起来很有用。我们怎样把它从 fetch 转换成一个子程序呢?现在 Python 3 的明星 yield from 出场了。它让一个生成器代表另一个生成器。

To see how, let us return to our simple generator example:

为了看看怎么做,让我们回到我们简单的生成器示例:

>>> def gen_fn():... result = yield 1... print('result of yield: {}'.format(result))... result2 = yield 2... print('result of 2nd yield: {}'.format(result2))... return 'done'...

To call this generator from another generator, delegate to it with yield from:

要从另一个生成器调用这个生成器,通过yield from 来委托给它:

>>> # Generator function:>>> def caller_fn():... gen = gen_fn()... rv = yield from gen... print('return value of yield-from: {}'... .format(rv))...>>> # Make a generator from the>>> # generator function.>>> caller = caller_fn()

The caller generator acts as if it were gen, the generator it is delegating to:

生成器 caller 表现的就像它是 gen 一样,这个生成器是通过委托代理的:

>>> caller.send(None)1>>> caller.gi_frame.f_lasti15>>> caller.send('hello')result of yield: hello2>>> caller.gi_frame.f_lasti # Hasn't advanced.15>>> caller.send('goodbye')result of 2nd yield: goodbyereturn value of yield-from: doneTraceback (most recent call last):File "<input>", line 1, in <module>StopIteration

While caller yields from gen, caller does not advance. Notice that its instruction pointer remains at 15, the site of its yield from statement, even while the inner generator gen advances from one yield statement to the next.8 From our perspective outside caller, we cannot tell if the values it yields are from caller or from the generator it delegates to. And from inside gen, we cannot tell if values are sent in from caller or from outside it. The yield from statement is a frictionless channel, through which values flow in and out of gen until gencompletes.

当 caller 通过 yields from 代理 gen, caller 不会前进。可以看到它的指针停留在15,即它的 yield from 语句的位置, 即使内部的生成器 gen 通过一个 yield 语句前进到下一个。我们从 caller 外面观察到,我们不知道它产生的值来自 caller 还是从它代表的生成器。从内部的 gen 来看,我们不知道值是通过 caller 还是外部发送的。yield from 语句是一个光滑的管道,通过它值可以从 gen 流入和流出直到 gen完成。

A coroutine can delegate work to a sub-coroutine with yield from and receive the result of the work. Notice, above, that caller printed “return value of yield-from: done”. When gen completed, its return value became the value of the yield fromstatement in caller:

协程可以将工作委托给具有yield from 的子协程,并接收工作的结果。注意,上面的 caller 打印 “return value of yield-from: done”。 当 gen 完成时,其返回值成为 caller 中 yield from语句的值:

rv = yield from gen

Earlier, when we criticized callback-based async programming, our most strident complaint was about “stack ripping”: when a callback throws an exception, the stack trace is typically useless. It only shows that the event loop was running the callback, not why. How do coroutines fare?

早些时候,当我们批评基于回调的异步编程时,我们最强烈的投诉是关于“堆栈撕裂stack ripping“: 当回调抛出异常时,堆栈跟踪通常是无用的。它只显示事件循环正在运行回调,而不是为什么。协程又是如何处理的?

>>> def gen_fn():... raise Exception('my error')>>> caller = caller_fn()>>> caller.send(None)Traceback (most recent call last):File "<input>", line 1, in <module>File "<input>", line 3, in caller_fnFile "<input>", line 2, in gen_fnException: my error

This is much more useful! The stack trace shows caller_fn was delegating to gen_fn when it threw the error. Even more comforting, we can wrap the call to a sub-coroutine in an exception handler, the same is with normal subroutines:

这更有用! 堆栈跟踪显示 caller_fn 在委托gen_fn 时抛出错误。更令人欣慰的是,我们可以将调用子协程包装到异常处理中的,同样的是使用普通的子程序:

>>> def gen_fn():... yield 1... raise Exception('uh oh')...>>> def caller_fn():... try:... yield from gen_fn()... except Exception as exc:... print('caught {}'.format(exc))...>>> caller = caller_fn()>>> caller.send(None)1>>> caller.send('hello')caught uh oh

So we factor logic with sub-coroutines just like with regular subroutines. Let us factor some useful sub-coroutines from our fetcher. We write a read coroutine to receive one chunk:

所以,我们使用子协程,就像使用常规协程一样。让我们从 fetcher 中分解出一些有用的子协程。我们写一个 read 协程来接收一个块:

def read(sock):f = Future()def on_readable():f.set_result(sock.recv(4096))selector.register(sock.fileno(), EVENT_READ, on_readable)chunk = yield f # Read one chunk.selector.unregister(sock.fileno())return chunk

We build on read with a read_all coroutine that receives a whole message:

我们使用 read 协程构建 read_all 协程,它接收一条完整的消息:

def read_all(sock):response = []# Read whole response.chunk = yield from read(sock)while chunk:response.append(chunk)chunk = yield from read(sock)return b''.join(response)

If you squint the right way, the yield from statements disappear and these look like conventional functions doing blocking I/O. But in fact, read and read_all are coroutines. Yielding from read pauses read_all until the I/O completes. While read_all is paused, asyncio’s event loop does other work and awaits other I/O events; read_all is resumed with the result of read on the next loop tick once its event is ready.

如果你以正确的方式看待,如果 yield from 语句小时,这些看起来就像传统的 I/O 阻塞函数。但事实上,read 和 read_all 是协程。执行 yield from 时 read 暂停 read_all 直到 I/O 读取完成,当 read_all 暂停时,asyncio的事件循环执行其他工作和等待其他 I/O 事件;当事件准备就绪后的下一个循环中,read_all 恢复并返回 read的结果。

At the stack’s root, fetch calls read_all:

在栈的根, fetch 调用 read_all:

class Fetcher:def fetch(self):# ... connection logic from above, then:sock.send(request.encode('ascii'))self.response = yield from read_all(sock)

Miraculously, the Task class needs no modification. It drives the outer fetchcoroutine just the same as before:

神奇的,Task类不需要修改。它与之前一样驱动外部 fetch 协程:

Task(fetcher.fetch())loop()

When read yields a future, the task receives it through the channel of yield fromstatements, precisely as if the future were yielded directly from fetch. When the loop resolves a future, the task sends its result into fetch, and the value is received by read, exactly as if the task were driving read directly:

当 read 产生 future 时,任务通过 yield from 语句的通道接收它,就如同 future 直接从 fetch 获得。当事件循环执行 futrure 的时候,任务把结果发送给 fetch,这个结果值由 read 接收,就像任务直接驱动 read:

To perfect our coroutine implementation, we polish out one mar: our code uses yield when it waits for a future, but yield from when it delegates to a sub-coroutine. It would be more refined if we used yield from whenever a coroutine pauses. Then a coroutine need not concern itself with what type of thing it awaits.

为了完善我们协程执行,我们打磨掉一个瑕疵: 我们的代码在等待 future 的时候用 yield, 委托给一个子协程的时候使用 yield from。如果我们在每一个协程暂停的时候使用 yield from,它会更精确。这样协程不需要关心它等待的事情是什么类型的。

We take advantage of the deep correspondence in Python between generators and iterators. Advancing a generator is, to the caller, the same as advancing an iterator. So we make our Future class iterable by implementing a special method:

我们利用 Python 生成器和迭代器之间深层对应的优点。对于调用者,我们像升级生成器一样升级迭代器。所以我们可以通过实现一个特殊方法使我们的 Future 类可迭代:

# Method on Future class.def __iter__(self):# Tell Task to resume me here.yield selfreturn self.result

The future’s __iter__ method is a coroutine that yields the future itself. Now when we replace code like this:

future 的 __iter__ 方法是一个协程,它产生自 future 本身。现在我们像这样替换代码:

# f is a Future.yield f

…with this:

…像这样:

# f is a Future.yield from f

…the outcome is the same! The driving Task receives the future from its call to send, and when the future is resolved it sends the new result back into the coroutine.

…结果是一样的!驱动任务通过调用 send 接收 future,并且当future 被执行完成时,将新的结果发送回协程。

What is the advantage of using yield from everywhere? Why is that better than waiting for futures with yield and delegating to sub-coroutines with yield from? It is better because now, a method can freely change its implementation without affecting the caller: it might be a normal method that returns a future that will resolve to a value, or it might be a coroutine that contains yield from statements and returns a value. In either case, the caller need only yield from the method in order to wait for the result.

在任何地方使用 yield from 的优势是什么呢?为什么这样比通过 yield 等待 futures 并且通过 yield from 委托代理给子协程更好呢?它更好因为现在,一个方法可以自由的改变它的实现并且不影响它的调用者:它可以是一个普通方法返回一个可以执行出一个结果值的 future,或者是一个包含 yield from 语句并且可以返回一个结果值的协程。在任一情况下,调用者只需要 yield from 这个方法来等待结果。

Gentle reader, we have reached the end of our enjoyable exposition of coroutines in asyncio. We peered into the machinery of generators, and sketched an implementation of futures and tasks. We outlined how asyncio attains the best of both worlds: concurrent I/O that is more efficient than threads and more legible than callbacks. Of course, the real asyncio is much more sophisticated than our sketch. The real framework addresses zero-copy I/O, fair scheduling, exception handling, and an abundance of other features.

亲爱的读者,我们已经来到了愉快的地讨论asyncio中协程的终点。我们探讨了生成器的机制,并草拟了一个 futures 和 tasks 的实现。我们概述了 asyncio 与其他两种实现相比,如何成为最好的:并发 I/O 比多线程更有效率,比回调更可靠。当然,真正的 asyncio 比我们的草图复杂的多。真正的框架解决了零拷贝 I/O,公平调度,异常处理和大量其他功能。

To an asyncio user, coding with coroutines is much simpler than you saw here. In the code above we implemented coroutines from first principles, so you saw callbacks, tasks, and futures. You even saw non-blocking sockets and the call to select. But when it comes time to build an application with asyncio, none of this appears in your code. As we promised, you can now sleekly fetch a URL:

对于 asyncio 用户,使用协程编码比你在这里看到的简单多了。这里的代码中我们我们实现协程从第一个原则,所以你看到了一系列回调,任务和 futures。你甚至看到了非阻塞的 sockets 和调用 select。但当使用 asyncio 构建应用程序时,这些都不会出现在您的代码中。正如我们承诺的,你现在可以顺利地获取一个URL:

@asyncio.coroutinedef fetch(self, url):response = yield from self.session.get(url)body = yield from response.read()

Satisfied with this exposition, we return to our original assignment: to write an async web crawler, using asyncio.

完成了这些解释,让我们回到我们最初的任务:使用asyncio写一个异步的网络爬虫。

Coordinating Coroutines 使用协程

We began by describing how we want our crawler to work. Now it is time to implement it with asyncio coroutines.

我们之前描述了我们希望爬虫如何工作。现在是时候通过 asyncio 协程实现。

Our crawler will fetch the first page, parse its links, and add them to a queue. After this it fans out across the website, fetching pages concurrently. But to limit load on the client and server, we want some maximum number of workers to run, and no more. Whenever a worker finishes fetching a page, it should immediately pull the next link from the queue. We will pass through periods when there is not enough work to go around, so some workers must pause. But when a worker hits a page rich with new links, then the queue suddenly grows and any paused workers should wake and get cracking. Finally, our program must quit once its work is done.

我们的爬虫会抓取第一个页面,解析它里面的链接,之后保存链接到队列中。之后它浏览过所有网站,并同时抓取页面。但为了限制客户端和服务器的负载,我们希望给运行的 worker 有一些最大数量限制,同时不能产生更多的。当一个 worker 完成页面抓取后,它应该立刻从队列中拉取下一个链接。当没有足够的工作可以运行时,我们会放空一些时间段,所以一些 worker 需要被暂停。但是当一个 worker 点击了一个包含很多新链接的页面时,队列突然增长,任何暂停的 worker 都应该醒来并开始工作。最后,我们的程序必须在其工作完成后退出。

Imagine if the workers were threads. How would we express the crawler’s algorithm? We could use a synchronized queue9 from the Python standard library. Each time an item is put in the queue, the queue increments its count of “tasks”. Worker threads call task_done after completing work on an item. The main thread blocks on Queue.join until each item put in the queue is matched by a task_donecall, then it exits.

想像一下如果 worker 是线程。我们将如何描述爬虫的算法?我们可以使用 Python 标准库中的同步队列9。每次一个项目被放入队列,队列都会增加其“任务”的计数。工作线程在完成一个项目的工作后调用 task_done。主线程在 Queue.join 项目加入队列后开始阻塞,直到每一个放入队列的项目被调用的 task_done 所匹配,然后退出。

Coroutines use the exact same pattern with an asyncio queue! First we import it10:

协程可以通过 asyncio queue 异步队列来实现相同的模式!第一步引入他:

try:from asyncio import JoinableQueue as Queueexcept ImportError:# In Python 3.5, asyncio.JoinableQueue is# merged into Queue.from asyncio import Queue

We collect the workers’ shared state in a crawler class, and write the main logic in its crawl method. We start crawl on a coroutine and run asyncio’s event loop until crawl finishes:

我们在爬虫类中收集 worker 的共享状态,并在它的 crawl 方法中编写主要逻辑。我们通过协程启动 crawl 并运行 asyncio 的事件循环,直到 crawl 结束:

loop = asyncio.get_event_loop()crawler = crawling.Crawler('http://xkcd.com',max_redirect=10)loop.run_until_complete(crawler.crawl())

The crawler begins with a root URL and max_redirect, the number of redirects it is willing to follow to fetch any one URL. It puts the pair (URL, max_redirect) in the queue. (For the reason why, stay tuned.)

爬虫以根 URL 和抓取任何一个 URL 期望的最大重定向次数 max_redirect 开始。并把一对 (URL, max_redirect) 放入队列中。(关于为什么这样做,请继续往下看)

class Crawler:def __init__(self, root_url, max_redirect):self.max_tasks = 10self.max_redirect = max_redirectself.q = Queue()self.seen_urls = set()# aiohttp's ClientSession does connection pooling and# HTTP keep-alives for us.self.session = aiohttp.ClientSession(loop=loop)# Put (URL, max_redirect) in the queue.self.q.put((root_url, self.max_redirect))

The number of unfinished tasks in the queue is now one. Back in our main script, we launch the event loop and the crawl method:

队列中现在未完成的任务数量的是一个。回到我们的主脚本,我们启动事件循环和 crawl 方法:

loop.run_until_complete(crawler.crawl())

The crawl coroutine kicks off the workers. It is like a main thread: it blocks on join until all tasks are finished, while the workers run in the background.crawl 协程启动 worker。它像一个主线程:从 join 开始阻塞直到所有任务完成,而 worker 在后台运行。

@asyncio.coroutinedef crawl(self):"""Run the crawler until all work is done."""workers = [asyncio.Task(self.work())for _ in range(self.max_tasks)]# When all work is done, exit.yield from self.q.join()for w in workers:w.cancel()

If the workers were threads we might not wish to start them all at once. To avoid creating expensive threads until it is certain they are necessary, a thread pool typically grows on demand. But coroutines are cheap, so we simply start the maximum number allowed.

如果每个 worker 是启动一个线程,我们或许不希望一次全部启动它们。来避免创建昂贵的线程在还没有确定他们是否必要的时候,一个线程池通过根据需求增加。但是协程很便宜,所以我们可以简单的启动并达到我们设置的允许的最大数量。

It is interesting to note how we shut down the crawler. When the join future resolves, the worker tasks are alive but suspended: they wait for more URLs but none come. So, the main coroutine cancels them before exiting. Otherwise, as the Python interpreter shuts down and calls all objects’ destructors, living tasks cry out:

注意我们如何关闭爬虫是必要的。当 join 加入的 future 都执行完毕,worker 任务都或者并被暂停:他们在等待更多的 URL,但没有结果。因此,主协程在退出之前取消他们。否则,当 Python 解释器关闭并且回收所有对象资源时,活着的任务就崩溃了:

ERROR:asyncio:Task was destroyed but it is pending!

And how does cancel work? Generators have a feature we have not yet shown you. You can throw an exception into a generator from outside:cancel 是如何工作的呢?生成器有一个我们还没有展示给你的特性。你可以从外部将异常抛出到生成器中:

>>> gen = gen_fn()>>> gen.send(None) # Start the generator as usual.1>>> gen.throw(Exception('error'))Traceback (most recent call last):File "<input>", line 3, in <module>File "<input>", line 2, in gen_fnException: error

The generator is resumed by throw, but it is now raising an exception. If no code in the generator’s call stack catches it, the exception bubbles back up to the top. So to cancel a task’s coroutine:

生成器由 throw 唤醒,当是它此时抛出一个异常。如果生成器的调用栈没有代码中捕获它,这个异常将冒泡回到顶部。所以为了取消任务的协程:

# Method of Task class.def cancel(self):self.coro.throw(CancelledError)

Wherever the generator is paused, at some yield from statement, it resumes and throws an exception. We handle cancellation in the task’s step method:

无论生成器何时暂停,在某些 yield from 语句中,它会恢复并抛出异常。我们在任务的 step 方法中处理取消:

# Method of Task class.def step(self, future):try:next_future = self.coro.send(future.result)except CancelledError:self.cancelled = Truereturnexcept StopIteration:returnnext_future.add_done_callback(self.step)

Now the task knows it is cancelled, so when it is destroyed it does not rage against the dying of the light.

现在任务直到它被取消了,所以当它被销毁时他不会愤怒反抗消亡。

Once crawl has canceled the workers, it exits. The event loop sees that the coroutine is complete (we shall see how later), and it too exits:

一旦 crawl 取消了 worker,它就退出了。事件循环看到协程是完成了的(我们将在稍后看到),于是它也退出了:

loop.run_until_complete(crawler.crawl())

The crawl method comprises all that our main coroutine must do. It is the worker coroutines that get URLs from the queue, fetch them, and parse them for new links. Each worker runs the work coroutine independently:crawl 方法包括我们的主协程必须做的所有事情。它是 worker 协程,从队列拉取 URL,抓取它们,并解析它们得到新的链接。每个 worker 独立运行 work 协程:

@asyncio.coroutinedef work(self):while True:url, max_redirect = yield from self.q.get()# Download page and add new links to self.q.yield from self.fetch(url, max_redirect)self.q.task_done()

Python sees that this code contains yield from statements, and compiles it into a generator function. So in crawl, when the main coroutine calls self.work ten times, it does not actually execute this method: it only creates ten generator objects with references to this code. It wraps each in a Task. The Task receives each future the generator yields, and drives the generator by calling send with each future’s result when the future resolves. Because the generators have their own stack frames, they run independently, with separate local variables and instruction pointers.

Python 看到这些代码包含 yield from 语句,会将其编译程一个生成器函数。所以在 crawl 中,当主协程调用 self.work 十次时,它实际上不执行此方法:它只创建十个生成器对象引用此代码。它将每个任务包装在一个 Task 中。Task 接收每一个生成器产生的 future,并且通过调用 send 获取每个 future 执行完的结果来驱动生成器。因为生成器有它们自己的堆栈,所以它们独立运行,具有单独的局部变量和指令指针。

The worker coordinates with its fellows via the queue. It waits for new URLs with:

worker 通过队列与其同事协调。它等通过这句待新的 URL :

url, max_redirect = yield from self.q.get()

The queue’s get method is itself a coroutine: it pauses until someone puts an item in the queue, then resumes and returns the item.

对了的 get 方法本身是一个协程:它将暂停,直到有人将一个项放入队列,然后就会恢复并返回项目。

Incidentally, this is where the worker will be paused at the end of the crawl, when the main coroutine cancels it. From the coroutine’s perspective, its last trip around the loop ends when yield from raises a CancelledError.

顺便说一下,当主协程取消它,worker 将在爬取结束时暂停。从协程的角度来看,当 yield from 引发一个 CancelledError 时,它的最后一次循环结束。

When a worker fetches a page it parses the links and puts new ones in the queue, then calls task_done to decrement the counter. Eventually, a worker fetches a page whose URLs have all been fetched already, and there is also no work left in the queue. Thus this worker’s call to task_done decrements the counter to zero. Then crawl, which is waiting for the queue’s join method, is unpaused and finishes.

当 worker 抓取一个页面并解析新的链接放入队列,然后调用 task_done 来递减计数器。最终,一个 worker 抓取了一个所有在它上面的 URL 都已经被抓取过的页面,这是队列中将没有剩余的工作。因此,这个 worker 调用 task_done 的将计数器减少为零。之后,等待对了 join 方法的 crawl 将被取消暂停并完成。

We promised to explain why the items in the queue are pairs, like:

我们承诺过解释为什么队列中的项目是成对的,像这样:

# URL to fetch, and the number of redirects left.('http://xkcd.com/353', 10)

New URLs have ten redirects remaining. Fetching this particular URL results in a redirect to a new location with a trailing slash. We decrement the number of redirects remaining, and put the next location in the queue:

新的 URL 有十个重定向。获取这个特定的 URL 会导致一个重定向到带有尾部斜杠的新位置。我们减少剩余的重定向数,并将下一个位置放入队列:

# URL with a trailing slash. Nine redirects left.('http://xkcd.com/353/', 9)

The aiohttp package we use would follow redirects by default and give us the final response. We tell it not to, however, and handle redirects in the crawler, so it can coalesce redirect paths that lead to the same destination: if we have already seen this URL, it is in self.seen_urls and we have already started on this path from a different entry point:

我们使用的 aiohttp 包将遵循默认的重定向,并给我们最后的响应。然而,我们不告诉它,并且处理爬虫中的重定向,因此它可能合并到指向相同目标的重定向地址:如我我们已经看到过这个 URL ,它在 self.seen_urls 中并且我们已经从其他入口启动并获取过了这条路径。

The crawler fetches “foo” and sees it redirects to “baz”, so it adds “baz” to the queue and to seen_urls. If the next page it fetches is “bar”, which also redirects to “baz”, the fetcher does not enqueue “baz” again. If the response is a page, rather than a redirect, fetch parses it for links and puts new ones in the queue.

爬虫获取”foo”并且看到它重定向到“baz”, 因此它添加“baz”到队列和 seen_urls 中。如果它获取的下一页是“bar”,它也重定向到“baz”,爬虫不会再次入队“baz”。如果响应是一个页面,而不是一个重定向,fetch 解析它的链接,并将新的链接加入队列中。

@asyncio.coroutinedef fetch(self, url, max_redirect):# Handle redirects ourselves.response = yield from self.session.get(url, allow_redirects=False)try:if is_redirect(response):if max_redirect > 0:next_url = response.headers['location']if next_url in self.seen_urls:# We have been down this path before.return# Remember we have seen this URL.self.seen_urls.add(next_url)# Follow the redirect. One less redirect remains.self.q.put_nowait((next_url, max_redirect - 1))else:links = yield from self.parse_links(response)# Python set-logic:for link in links.difference(self.seen_urls):self.q.put_nowait((link, self.max_redirect))self.seen_urls.update(links)finally:# Return connection to pool.yield from response.release()

If this were multithreaded code, it would be lousy with race conditions. For example, the worker checks if a link is in seen_urls, and if not the worker puts it in the queue and adds it to seen_urls. If it were interrupted between the two operations, then another worker might parse the same link from a different page, also observe that it is not in seen_urls, and also add it to the queue. Now that same link is in the queue twice, leading (at best) to duplicated work and wrong statistics.

如果这是多线程代码,它将是讨厌的条件竞争。例如,worker 检查链接是否在 seen_urls 中,如果不是,则将其放入队列并将其添加到 seen_urls 中。 如果它在两个操作之间中断,则另一个 worker 可能从不同的页面解析相同的链接,还观察到它不在 seen_urls,并且也将其添加到队列。现在同一个链接在队列中两次,导致(顶多)重复的工作和错误的统计。

However, a coroutine is only vulnerable to interruption at yield from statements. This is a key difference that makes coroutine code far less prone to races than multithreaded code: multithreaded code must enter a critical section explicitly, by grabbing a lock, otherwise it is interruptible. A Python coroutine is uninterruptible by default, and only cedes control when it explicitly yields.

但是,协程只受到 yield from 语句中断的影响。这是一个关键区别,使得协同代码比多线程代码更不容易发生竞争:多线程代码必须通过获得锁来显式地进入临界区,否则它是可中断的。 Python 协程在默认情况下是不可中断的,并且只有在它显式生成时才放弃控制。

We no longer need a fetcher class like we had in the callback-based program. That class was a workaround for a deficiency of callbacks: they need some place to store state while waiting for I/O, since their local variables are not preserved across calls. But the fetch coroutine can store its state in local variables like a regular function does, so there is no more need for a class.

我们不再需要像我们在基于回调的程序中一样的 fetcher 类。该类是为了满足回调的不足的解决方法:在等待 I/O 时,它们需要一些地方来存储状态,因为它们的局部变量不会跨越调用保留。但是 fetch 协程可以像常规函数那样将其状态存储在局部变量中,因此不再需要类。

When fetch finishes processing the server response it returns to the caller, work. The work method calls task_done on the queue and then gets the next URL from the queue to be fetched.

当 fetch 完成处理服务器响应时,它返回到调用者 work。work 方法在队列上调用 task_done,然后从队列中获取下一个要获取的 URL 。

When fetch puts new links in the queue it increments the count of unfinished tasks and keeps the main coroutine, which is waiting for q.join, paused. If, however, there are no unseen links and this was the last URL in the queue, then when work calls task_done the count of unfinished tasks falls to zero. That event unpauses join and the main coroutine completes.

当 fetch 将新的链接放入队列时,它增加未完成任务的计数,并保持正在等待 q.join而暂停的主协程。然而,如果没有 unseen links,这是队列中的最后一个 URL,那么当 work 调用 task_done 时,未完成任务的计数降为零。该事件取消了等待 join 并且主协程完成。

The queue code that coordinates the workers and the main coroutine is like this11:

协调 worker 和主协程的队列代码是这样的[^ 9]:

class Queue:def __init__(self):self._join_future = Future()self._unfinished_tasks = 0# ... other initialization ...def put_nowait(self, item):self._unfinished_tasks += 1# ... store the item ...def task_done(self):self._unfinished_tasks -= 1if self._unfinished_tasks == 0:self._join_future.set_result(None)@asyncio.coroutinedef join(self):if self._unfinished_tasks > 0:yield from self._join_future

The main coroutine, crawl, yields from join. So when the last worker decrements the count of unfinished tasks to zero, it signals crawl to resume, and finish.

主协程 crawl 从 join 中产生。因此,当最后一个 worker 将未完成任务的计数减少为零时,它指示 crawl 恢复并且完成。

The ride is almost over. Our program began with the call to crawl:

流程基本完成了,我们的程序从调用 crawl 开始:

loop.run_until_complete(self.crawler.crawl())

How does the program end? Since crawl is a generator function, calling it returns a generator. To drive the generator, asyncio wraps it in a task:

程序如何结束?因为 crawl 是一个生成器函数,所以调用它会返回一个生成器。为了驱动生成器,asyncio将它包装在一个 task 中:

class EventLoop:def run_until_complete(self, coro):"""Run until the coroutine is done."""task = Task(coro)task.add_done_callback(stop_callback)try:self.run_forever()except StopError:passclass StopError(BaseException):"""Raised to stop the event loop."""def stop_callback(future):raise StopError

When the task completes, it raises StopError, which the loop uses as a signal that it has arrived at normal completion.

当任务完成时,它产生 StopError,loop 把它作为已经正常结束的信号。

But what’s this? The task has methods called add_done_callback and result? You might think that a task resembles a future. Your instinct is correct. We must admit a detail about the Task class we hid from you: a task is a future.

但这是什么?task 有一个称为 add_done_callback 和 result 的方法?你可能认为任务类似于future。你的直觉是正确的。我们必须承认我们隐藏的 Task 类的细节:一个 task 是一个future。

class Task(Future):"""A coroutine wrapped in a Future."""

Normally a future is resolved by someone else calling set_result on it. But a task resolves itself when its coroutine stops. Remember from our earlier exploration of Python generators that when a generator returns, it throws the special StopIteration exception:

通常,future 由其他人调用 set_result 产生结果。但是一个 task 在它的协程停止时自行产生结果。记住我们早些时候探索 Python 生成器时,当一个生成器返回时,它会抛出特殊的 StopIteration 异常:

# Method of class Task.def step(self, future):try:next_future = self.coro.send(future.result)except CancelledError:self.cancelled = Truereturnexcept StopIteration as exc:# Task resolves itself with coro's return# value.self.set_result(exc.value)returnnext_future.add_done_callback(self.step)

So when the event loop calls task.add_done_callback(stop_callback), it prepares to be stopped by the task. Here is run_until_complete again:

所以当事件循环调用 task.add_done_callback(stop_callback 时,它准备被任务停止。这里又是 run_until_complete:

# Method of event loop.def run_until_complete(self, coro):task = Task(coro)task.add_done_callback(stop_callback)try:self.run_forever()except StopError:pass

When the task catches StopIteration and resolves itself, the callback raises StopError from within the loop. The loop stops and the call stack is unwound to run_until_complete. Our program is finished.

当任务捕获 StopIteration 并且自己解析时,回调从循环中引发 StopError。循环停止,调用堆栈从 run_until_complete 解开。 我们的程序完成了。

Conclusion

Increasingly often, modern programs are I/O-bound instead of CPU-bound. For such programs, Python threads are the worst of both worlds: the global interpreter lock prevents them from actually executing computations in parallel, and preemptive switching makes them prone to races. Async is often the right pattern. But as callback-based async code grows, it tends to become a dishevelled mess. Coroutines are a tidy alternative. They factor naturally into subroutines, with sane exception handling and stack traces.

越来越多地,现代程序是 I/O 绑定而不是 CPU 绑定。对于这样的程序,Python 线程是很糟糕的:全局解释器锁防止它们实际上并行执行计算,并且抢先切换使它们容易出现竞争。异步通常是正确的模式。但是随着基于回调的异步代码的增长,它往往成为一个混乱的混乱。协程是一个整洁的替代品。他们自然地考虑子程序,具有正确的异常处理和堆栈跟踪。

If we squint so that the yield from statements blur, a coroutine looks like a thread doing traditional blocking I/O. We can even coordinate coroutines with classic patterns from multi-threaded programming. There is no need for reinvention. Thus, compared to callbacks, coroutines are an inviting idiom to the coder experienced with multithreading.

如果我们眯着眼睛,使得 yield from 语句模糊,协程看起来像是执行传统的阻塞 I/O 的线程。我们甚至可以使用多线程编程中的经典模式来协调协程。没有必要改造。因此,协程对于富有多线程编程经验的程序员来说是一个受欢迎的语法。

But when we open our eyes and focus on the yield from statements, we see they mark points when the coroutine cedes control and allows others to run. Unlike threads, coroutines display where our code can be interrupted and where it cannot. In his illuminating essay “Unyielding”12, Glyph Lefkowitz writes, “Threads make local reasoning difficult, and local reasoning is perhaps the most important thing in software development.” Explicitly yielding, however, makes it possible to “understand the behavior (and thereby, the correctness) of a routine by examining the routine itself rather than examining the entire system.”

但是当我们打开我们的眼睛并专注于 yield from 语句时,我们看到它们在协程退出控制并允许其他人运行时标记了重点。与线程不同,协同程序显示我们的代码可以中断的地方,而线程不能。在他的论文“Unyielding“[^ 4]中,Glyph Lefkowitz写道,“线程使得局部推理变得困难,局部推理也许是软件开发中最重要的。“然而,显式产生(Explicitly yielding)使得“通过检查程序本身而不是检查整个系统来“理解程序的行为的(正确性)“变得可能。

This chapter was written during a renaissance in the history of Python and async. Generator-based coroutines, whose devising you have just learned, were released in the “asyncio” module with Python 3.4 in March 2014. In September 2015, Python 3.5 was released with coroutines built in to the language itself. These native coroutinesare declared with the new syntax “async def”, and instead of “yield from”, they use the new “await” keyword to delegate to a coroutine or wait for a Future.

这篇文章是在 Python 和 async 的历史上复兴期间写的。基于生成器的协程,它的设计你刚刚学会了,在2014年3月的 Python 3.4 的“asyncio”模块中发布。2015年9月,Python 3.5 发布了内置语言本身的协同程序。这些本地协程用新语法“async def”声明,而不是“yield from”,它们使用新的“await”关键字来委派协程或等待 Future 。

Despite these advances, the core ideas remain. Python’s new native coroutines will be syntactically distinct from generators but work very similarly; indeed, they will share an implementation within the Python interpreter. Task, Future, and the event loop will continue to play their roles in asyncio.

尽管有这些进展,核心思想仍然不变。Python 的新本地协同程序在语法上不同于生成器,但工作非常相似; 实际上,他们将在 Python 解释器中共享一个实现。Task, Future 和 event loop 将继续在 asyncio 中发挥他们的角色。

Now that you know how asyncio coroutines work, you can largely forget the details. The machinery is tucked behind a dapper interface. But your grasp of the fundamentals empowers you to code correctly and efficiently in modern async environments.

现在你知道 asyncio 协程如何工作,你可以在很大程度上忘记细节。机械被塞在一个整洁的接口后面。但是你对基础知识的掌握使你能够在现代异步环境中正确有效地编程。

[^11]: Jesse listed indications and contraindications for using async in “What Is Async, How Does It Work, And When Should I Use It?”, available at pyvideo.org. [^bayer]: Mike Bayer compared the throughput of asyncio and multithreading for different workloads in his “Asynchronous Python and Databases”: http://techspot.zzzeek.org/2015/02/15/asynchronous-python-and-databases/ [^11]: Jesse listed indications and contraindications for using async in “What Is Async, How Does It Work, And When Should I Use It?”:. Mike Bayer compared the throughput of asyncio and multithreading for different workloads in “Asynchronous Python and Databases”:[^16]: Guido introduced the standard asyncio library, called “Tulip” then, at PyCon 2013. [^16]: Guido introduced the standard asyncio library, called “Tulip” then, at PyCon 2013.

- Even calls to

sendcan block, if the recipient is slow to acknowledge outstanding messages and the system’s buffer of outgoing data is full. ↩ - http://www.kegel.com/c10k.html ↩

- Python’s global interpreter lock prohibits running Python code in parallel in one process anyway. Parallelizing CPU-bound algorithms in Python requires multiple processes, or writing the parallel portions of the code in C. But that is a topic for another day. ↩

- For a complex solution to this problem, see http://www.tornadoweb.org/en/stable/stack_context.html ↩

- The

@asyncio.coroutinedecorator is not magical. In fact, if it decorates a generator function and thePYTHONASYNCIODEBUGenvironment variable is not set, the decorator does practically nothing. It just sets an attribute,_is_coroutine, for the convenience of other parts of the framework. It is possible to use asyncio with bare generators not decorated with@asyncio.coroutineat all. ↩ - Python 3.5’s built-in coroutines are described in PEP 492, “Coroutines with async and await syntax.” ↩

- This future has many deficiencies. For example, once this future is resolved, a coroutine that yields it should resume immediately instead of pausing, but with our code it does not. See asyncio’s Future class for a complete implementation. ↩ ↩

- In fact, this is exactly how “yield from” works in CPython. A function increments its instruction pointer before executing each statement. But after the outer generator executes “yield from”, it subtracts 1 from its instruction pointer to keep itself pinned at the “yield from” statement. Then it yields to its caller. The cycle repeats until the inner generator throws

StopIteration, at which point the outer generator finally allows itself to advance to the next instruction. ↩ - https://docs.python.org/3/library/queue.html ↩ ↩

- https://docs.python.org/3/library/asyncio-sync.html ↩

- The actual

asyncio.Queueimplementation uses anasyncio.Eventin place of the Future shown here. The difference is an Event can be reset, whereas a Future cannot transition from resolved back to pending. ↩ - https://glyph.twistedmatrix.com/2014/02/unyielding.html ↩