This document describes Chromium’s high-level architecture.

Problem

It’s nearly impossible to build a rendering engine that never crashes or hangs. It’s also nearly impossible to build a rendering engine that is perfectly secure.

In some ways, the state of web browsers around 2006 was like that of the single-user, co-operatively multi-tasked operating systems of the past. As a misbehaving application in such an operating system could take down the entire system, so could a misbehaving web page in a web browser. All it took is one browser or plug-in bug to bring down the entire browser and all of the currently running tabs.

Modern operating systems are more robust because they put applications into separate processes that are walled off from one another. A crash in one application generally does not impair other applications or the integrity of the operating system, and each user’s access to other users’ data is restricted.

Architectural overview

We use separate processes for browser tabs to protect the overall application from bugs and glitches in the rendering engine. We also restrict access from each rendering engine process to others and to the rest of the system. In some ways, this brings to web browsing the benefits that memory protection and access control brought to operating systems.

We refer to the main process that runs the UI and manages tab and plugin processes as the “browser process” or “browser.” Likewise, the tab-specific processes are called “render processes” or “renderers.” The renderers use the Blink open-source layout engine for interpreting and laying out HTML.

Managing render processes

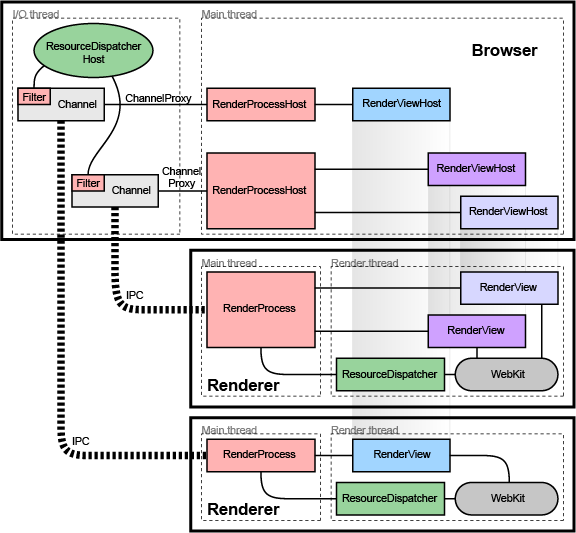

Each render process has a global RenderProcess object that manages communication with the parent browser process and maintains global state. The browser maintains a corresponding RenderProcessHost for each render process, which manages browser state and communication for the renderer. The browser and the renderers communicate using Chromium’s IPC system.

Managing views

Each render process has one or more RenderView objects, managed by the RenderProcess, which correspond to tabs of content. The corresponding RenderProcessHost maintains a RenderViewHost corresponding to each view in the renderer. Each view is given a view ID that is used to differentiate multiple views in the same renderer. These IDs are unique inside one renderer but not within the browser, so identifying a view requires a RenderProcessHost and a view ID. Communication from the browser to a specific tab of content is done through these RenderViewHost objects, which know how to send messages through their RenderProcessHost to the RenderProcess and on to the RenderView.

Components and interfaces

In the render process:

- The

RenderProcesshandles IPC with the correspondingRenderProcessHostin the browser. There is exactly oneRenderProcessobject per render process. This is how all browser ↔ renderer communication happens. - The

RenderViewobject communicates with its correspondingRenderViewHostin the browser process (via the RenderProcess), and our WebKit embedding layer. This object represents the contents of one web page in a tab or popup window

In the browser process:

- The

Browserobject represents a top-level browser window. - The

RenderProcessHostobject represents the browser side of a single browser ↔ renderer IPC connection. There is oneRenderProcessHostin the browser process for each render process. - The

RenderViewHostobject encapsulates communication with the remoteRenderView, and RenderWidgetHosthandles the input and painting for RenderWidget in the browser.

For more detailed information on how this embedding works, see the How Chromium displays web pages design document.

Sharing the render process

In general, each new window or tab opens in a new process. The browser will spawn a new process and instruct it to create a single RenderView.

Sometimes it is necessary or desirable to share the render process between tabs or windows. A web application opens a new window that it expects to communicate with synchronously, for example, using window.open in JavaScript. In this case, when we create a new window or tab, we need to reuse the process that the window was opened with. We also have strategies to assign new tabs to existing processes if the total number of processes is too large, or if the user already has a process open navigated to that domain. These strategies are described in Process Models.

Detecting crashed or misbehaving renderers

Each IPC connection to a browser process watches the process handles. If these handles are signaled, the render process has crashed and the tabs are notified of the crash. For now, we show a “sad tab” screen that notifies the user that the renderer has crashed. The page can be reloaded by pressing the reload button or by starting a new navigation. When this happens, we notice that there is no process and create a new one.

Sandboxing the renderer

Given the renderer is running in a separate process, we have the opportunity to restrict its access to system resources via sandboxing. For example, we can ensure that the renderer’s only access to the network is via its parent browser process. Likewise, we can restrict its access to the filesystem using the host operating system’s built-in permissions.

In addition to restricting the renderer’s access to the filesystem and network, we can also place limitations on its access to the user’s display and related objects. We run each render process on a separate Windows “Desktop.aspx)” which is not visible to the user. This prevents a compromised renderer from opening new windows or capturing keystrokes.

Giving back memory

Given renderers running in separate processes, it becomes straightforward to treat hidden tabs as lower priority. Normally, minimized processes on Windows have their memory automatically put into a pool of “available memory.” In low-memory situations, Windows will swap this memory to disk before it swaps out higher-priority memory, helping to keep the user-visible programs more responsive. We can apply this same principle to hidden tabs. When a render process has no top-level tabs, we can release that process’s “working set” size as a hint to the system to swap that memory out to disk first if necessary. Because we found that reducing the working set size also reduces tab switching performance when the user is switching between two tabs, we release this memory gradually. This means that if the user switches back to a recently used tab, that tab’s memory is more likely to be paged in than less recently used tabs. Users with enough memory to run all their programs will not notice this process at all: Windows will only actually reclaim such data if it needs it, so there is no performance hit when there is ample memory.

This helps us get a more optimal memory footprint in low-memory situations. The memory associated with seldom-used background tabs can get entirely swapped out while foreground tabs’ data can be entirely loaded into memory. In contrast, a single-process browser will have all tabs’ data randomly distributed in its memory, and it is impossible to separate the used and unused data so cleanly, wasting both memory and performance.

Plug-ins and Extensions

Firefox-style NPAPI plug-ins ran in their own process, separate from renderers. This is described in detail in Plugin Architecture.

The Site Isolation project aims to provide more isolation between renderers, an early deliverable for this project includes running Chrome’s HTML/JavaScript content extensions in isolated processes.