- Summary

- Introduction: Why Hardware Compositing?

- Part 1: Blink Rendering Basics

- Part 2: The Compositor

- Introducing the Compositor

- Whither the GPU?

- Architectural Interlude: The GPU Process

- The Command Buffer

- Resource Sharing & Synchronization

- Command Buffer Multiplexing

- Summary

- Recording: Painting from Blink’s Perspective

- The Commit: Handoff to the Compositor Thread

- Tree Activation

- Tiling

- Rasterization: Painting from cc/Skia’s perspective

- Drawing on the GPU, Tiling, and Quads

- Varied Scale Factors

- From WebKit to the Screen

This code is changing due to Slimming Paint (现在合并到Rendering Core了)and thus there may be large changes in the future. Note also that some class names may have changed (e.g. RenderObject to LayoutObject, RenderLayer to PaintLayer).

Summary

This document provides background and details on the implementation of hardware-accelerated compositing in Chrome.

Introduction: Why Hardware Compositing?

Traditionally, web browsers relied entirely on the CPU to render web page content. With capable GPUs now an integral part of even the smallest of devices, attention has turned on finding ways to more effectively use this underlying hardware to achieve better performance and power savings. Using the GPU to composite the contents of a web page can result in very significant speedups.

The benefits of hardware compositing come in three flavors:

Compositing page layers on the GPU can achieve far better efficiency than the CPU (both in terms of speed and power draw) in drawing and compositing operations that involve large numbers of pixels. The hardware is designed specifically for these types of workloads.

Expensive readbacks aren’t necessary for content already on the GPU (such as accelerated video, Canvas2D, or WebGL).

Parallelism between the CPU and GPU, which can operate at the same time to create an efficient graphics pipeline.

Lastly, before we begin, a big disclaimer: the Chrome graphics stack has evolved substantially over the last several years. This document will focus on the most advanced architecture at the time of writing, which is not the shipping configuration on all platforms. For a breakdown of what’s enabled where, see the GPU architecture roadmap. Code paths that aren’t under active development will be covered here only minimally.

Part 1: Blink Rendering Basics

The source code for the Blink rendering engine is vast, complex, and somewhat scarcely documented. In order to understand how GPU acceleration works in Chrome it’s important to first understand the basic building blocks of how Blink renders pages.

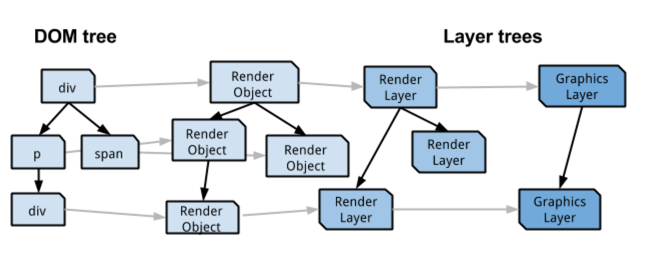

Nodes and the DOM tree

In Blink, the contents of a web page are internally stored as a tree of Node objects called the DOM tree. Each HTML element on a page as well as text that occurs between elements is associated with a Node. The top level Node of the DOM tree is always a Document Node.

From Nodes to RenderObjects

Each node in the DOM tree that produces visual output has a corresponding _RenderObject. _RenderObjects are stored in a parallel tree structure, called the _Render Tree. _A RenderObject knows how to paint the contents of the Node on a display surface. It does so by issuing the necessary draw calls to a _GraphicsContext. _A GraphicsContext is responsible for writing the pixels into a bitmap that eventually get displayed to the screen. In Chrome, the GraphicsContext wraps Skia, our 2D drawing library.

Traditionally most GraphicsContext calls became calls to an SkCanvas or SkPlatformCanvas, i.e. immediately painted into a software bitmap (see this document for more detail on this older model of how Chrome uses Skia). But to move painting off the main thread (covered in greater detail later in this document), these commands are now instead recorded into an SkPicture. The SkPicture is a serializable data structure that can capture and then later replay commands, similar to a display list.

From RenderObjects to RenderLayers

Each RenderObject is associated with a _RenderLayer _either directly or indirectly via an ancestor RenderObject.

Each RenderObject is associated with a RenderLayer either directly or indirectly via an ancestor RenderObject.

RenderObjects that share the same coordinate space (e.g. are affected by the same CSS transform) typically belong to the same RenderLayer. RenderLayers exist so that the elements of the page are composited in the correct order to properly display overlapping content, semi-transparent elements, etc. There’s a number of conditions that will trigger the creation of a new RenderLayer for a particular RenderObject, as defined in RenderBoxModelObject::requiresLayer() and overwritten for some derived classes. Common cases of RenderObject that warrant the creation of a RenderLayer:

- It’s the root object for the page

- It has explicit CSS position properties (relative, absolute or a transform)

- It is transparent

- Has overflow, an alpha mask or reflection

- Has a CSS filter

- Corresponds to element that has a 3D (WebGL) context or an accelerated 2D context

- Corresponds to a video element

Notice that there isn’t a one-to-one correspondence between RenderObjects and RenderLayers. A particular RenderObject is associated either with the RenderLayer that was created for it, if there is one, or with the RenderLayer of the first ancestor that has one.

RenderLayers form a tree hierarchy as well. The root node is the RenderLayer corresponding to the root element in the page and the descendants of every node are layers visually contained within the parent layer. The children of each RenderLayer are kept into two sorted lists both sorted in ascending order, the negZOrderList containing child layers with negative z-indices (and hence layers that go below the current layer) and the posZOrderList contain child layers with positive z-indices (layers that go above the current layer).

From RenderLayers to GraphicsLayers

To make use of the compositor, some (but not all) of the RenderLayers get their own backing surface (layers with their own backing surfaces are broadly referred to as compositing layers). Each RenderLayer either has its own GraphicsLayer (if it is a compositing layer) or uses the GraphicsLayer of its first ancestor that has one. This is similar to RenderObject’s relationship with RenderLayers.

Each GraphicsLayer has a GraphicsContext for the associated RenderLayers to paint into. The compositor is ultimately responsible for combining the bitmap output of GraphicsContexts together into a final screen image in a subsequent compositing pass.

While in theory every single RenderLayer could paint itself into a separate backing surface, in practice this could be quite wasteful in terms of memory (VRAM especially). In the current Blink implementation, one of the following conditions must to be met for a RenderLayer to get its own compositing layer (see CompositingReasons.h):

- Layer has 3D or perspective transform CSS properties

- Layer is used by element using accelerated video decoding

- Layer is used by a

- Layer is used for a composited plugin

- Layer uses a CSS animation for its opacity or uses an animated webkit transform

- Layer uses accelerated CSS filters

- Layer has a descendant that is a compositing layer

- Layer has a sibling with a lower z-index which has a compositing layer (in other words the layer overlaps a composited layer and should be rendered on top of it)

Layer Squashing

Never a rule without an exception. As mentioned above, GraphicsLayers can be costly in terms of memory and other resources (e.g. some critical operations have CPU time complexity proportional to the size of the GraphicsLayer tree). Many additional layers can be created for RenderLayers that overlap a RenderLayer with its own backing surface, which can be expensive.

We call intrinsic compositing reasons (e.g. a layer that has a 3D transform on it) “direct” compositing reasons. To prevent a “layer explosion” when many elements are on top of a layer with a direct compositing reason, Blink takes multiple RenderLayers overlapping a direct-compositing-reason RenderLayer and “squashes” them into a single backing store. This prevents the layer explosion caused by overlap. More detail motivating layer squashing can be found in this presentation, and more detail on the code in between RenderLayers and compositing layers can be found in this presentation; both are current as of approximately Jan 2014 although this code is undergoing significant change in 2014.

From GraphicsLayers to WebLayers to CC Layers

Only a couple more layers of abstraction to go before we get to Chrome’s compositor implementation! GraphicsLayers can represent their content via one or more WebLayers. These are interfaces that WebKit ports needed to implement; see Blink’s public/platform directory for interfaces such as WebContentsLayer.h or WebScrollbarLayer.h. Chrome’s implementations are in src/webkit/renderer/compositor_bindings which implement the abstract WebLayer interfaces using Chrome compositor layer types.

Putting it Together: The Compositing Forest

In summary, there are conceptually four parallel tree structures in place that serve slightly different purposes for rendering:

- The DOM tree, which is our fundamental retained model

- The RenderObject tree, which has a 1:1 mapping to the DOM tree’s visible nodes. RenderObjects know how to paint their corresponding DOM nodes.

- The RenderLayer tree, made up of RenderLayers that map to a RenderObject on the RenderObject tree. The mapping is many-to-one, as each RenderObject is either associated with its own RenderLayer or the RenderLayer of its first ancestor that has one. The RenderLayer tree preserves z-ordering amongst layers.

- The GraphicsLayer tree, mapping GraphicsLayers one-to-many RenderLayers.

Each GraphicsLayer has Web*Layers implemented in Chrome with Chrome compositor layers. It is these final “cc layers” (cc = Chrome compositor) that the compositor knows how to operate on.

From here on in this document “layer” is going to refer to a generic cc layer, since for hardware compositing these are the most interesting — but don’t be fooled, elsewhere when someone says “layer” they might be referring to any of the above constructs!

Now that we’ve (briefly) covered the data structures in Blink that link the DOM to the compositor, we’re ready to explore the compositor itself in earnest.

Part 2: The Compositor

Chrome’s compositor is a software library for managing GraphicsLayer trees and coordinating frame lifecycles. Code for it lives in the src/cc directory, outside of Blink.

Introducing the Compositor

Recall that rendering occurs in two phases: first paint, then composite. This allows the compositor to perform additional work on a per-compositing-layer basis. For instance, the compositor is responsible for applying the necessary transformations (as specified by the layer’s CSS transform properties) to each compositing layer’s bitmap before compositing it. Further, since painting of the layers is decoupled from compositing, invalidating one of these layers only results in repainting the contents of that layer alone and recompositing.

Every time the browser needs to make a new frame, the compositor draws. Note this (confusing) terminology distinction: drawing is the compositor combining layers into the final screen image; while painting is the population of layers’ backings (bitmaps with software rasterization; textures in hardware rasterization).

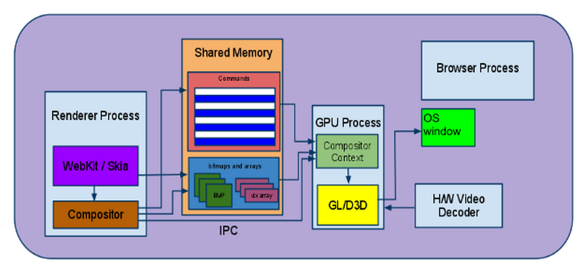

Whither the GPU?

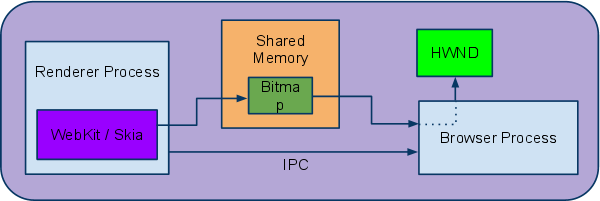

So how does the GPU come into play? The compositor can use the GPU to perform its drawing step. This is a significant departure from the old software rendering model in which the Renderer process passes (via IPC and shared memory) a bitmap with the page’s contents over to the Browser process for display (see “The Legacy Software Rendering Path” appendix for more on how that works).

In the hardware accelerated architecture, compositing happens on the GPU via calls to the platform specific 3D APIs (D3D on Windows; GL everywhere else). The Renderer’s compositor is essentially using the GPU to draw rectangular areas of the page (i.e. all those compositing layers, positioned relative to the viewport according to the layer tree’s transform hierarchy) into a single bitmap, which is the final page image.

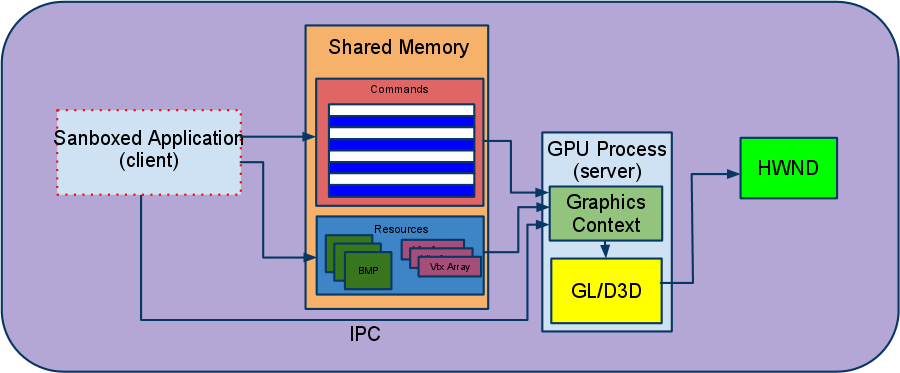

Architectural Interlude: The GPU Process

Before we go any further exploring the GPU commands the compositor generates, its important to understand how the renderer process issues any commands to the GPU at all. In Chrome’s multi-process model, we have a dedicated process for this task: the GPU process. The GPU process exists primarily for security reasons. Note that Android is an exception, where Chrome uses an in-process GPU implementation that runs as a thread in the Browser process. The GPU thread on Android otherwise behaves the same way as the GPU process on other platforms.

Restricted by its sandbox, the Renderer process (which contains an instance of Blink and of cc) cannot directly issue calls to the 3D APIs provided by the OS (GL / D3D). For that reason we use a separate process to access the device. We call this process the GPU Process. The GPU process is specifically designed to provide access to the system’s 3D APIs from within the Renderer sandbox or the even more restrictive Native Client “jail”. It works via a client-server model as follows:

- The client (code running in the Renderer or within a NaCl module), instead of issuing calls directly to the system APIs, serializes them and puts them in a ring buffer (the command buffer) residing in memory shared between itself and the server process.

- The server (GPU process running in a less restrictive sandbox that allows access to the platform’s 3D APIs) picks up the serialized commands from shared memory, parses them and executes the appropriate graphics calls.

The Command Buffer

The commands accepted by the GPU process are patterned closely after the GL ES 2.0 API (for example there’s a command corresponding to glClear, one to glDrawArrays, etc). Since most GL calls don’t have return values, the client and server can work mostly asynchronously which keeps the performance overhead fairly low. Any necessary synchronization between the client and the server, such as the client notifying the server that there’s additional work to be done, is handled via an IPC mechanism.

From the client’s perspective, an application has the option to either write commands directly into the command buffer or use the GL ES 2.0 API via a client side library that we provide which handles the serialization behind the scenes. Both the compositor and WebGL currently use the GL ES client side library for convenience. On the server side, commands received via the command buffer are converted to calls into either desktop OpenGL or Direct3D via ANGLE.

Resource Sharing & Synchronization

In addition to providing storage for the command buffer, Chrome uses shared memory for passing larger resources such as bitmaps for textures, vertex arrays, etc between the client and the server. See the command buffer documentation for more about the command format and data transfer.

Another construct, referred to as a mailbox, provides a means to share textures between command buffers and manage their lifetimes. The mailbox is a simple string identifier, which can be attached (consumed) to a local texture id for any command buffer, and then accessed through that texture id alias. Each texture id attached in this way holds a reference on the underlying real texture, and once all references are released by deleting the local texture ids, the real texture is also destroyed.

Sync points are used to provide non-blocking synchronization between command buffers that want to share textures via mailboxes. Inserting a sync point on command buffer A and then “waiting” on the sync point on command buffer B ensures that commands you then insert on B will not run before the commands that were inserted on A before the sync point.

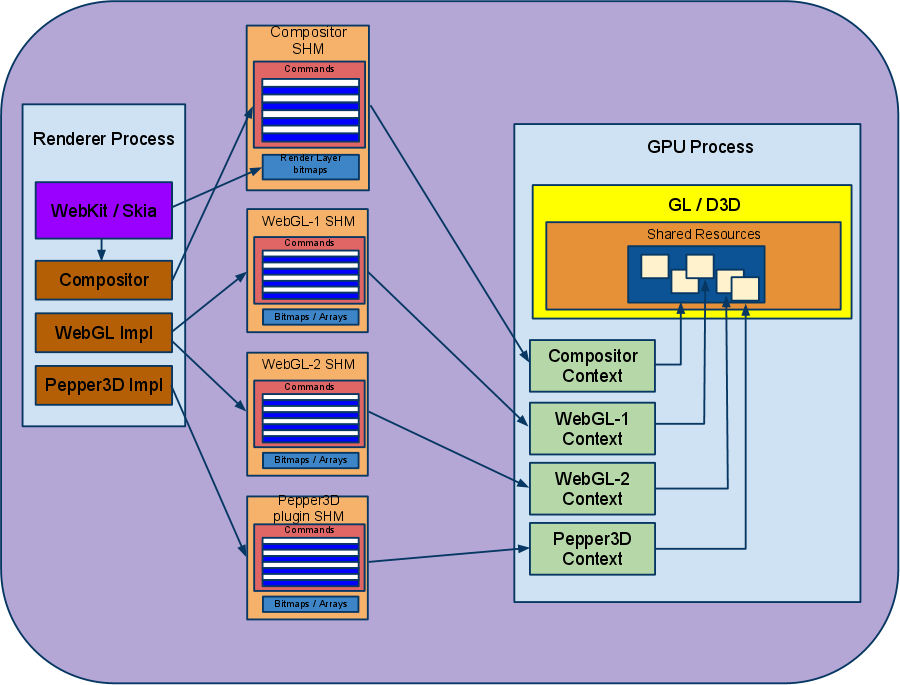

Command Buffer Multiplexing

Currently Chrome uses a single GPU process per browser instance, serving requests from all the renderer processes and any plugin processes. The GPU process can multiplex between multiple command buffers, each one of which is associated with its own rendering context.

Each Renderer can have multiple sources of GL, e.g. WebGL Canvas elements create GL command streams directly. Composition of layers whose contents are created directly on GPU works as follows: instead of rendering straight into the backbuffer, they render into a texture (using a Frame Buffer Object) that the compositor context grabs and uses when rendering that GraphicsLayer. It’s important to note that in order for the compositor’s GL context to have access to a texture generated by an offscreen GL context (i.e. the GL contexts used for the other GraphicsLayers’ FBOs), all GL contexts used by the GPU process are created such that they share resources.

The resulting architecture looks like this:

Summary

The GPU process architecture offers several benefits including:

- Security: The bulk of the rendering logic remains in the sandboxed Renderer process, and access to platform 3D APIs is limited to only the GPU process.

- Robustness: A GPU process crash (e.g. due to faulty drivers) doesn’t bring down the browser.

- Uniformity: Standardizing on OpenGL ES 2.0 as the rendering API for the browser regardless of the platform allows for a single, easier to maintain codebase across all OS ports of Chrome.

- Parallelism: The Renderer can quickly issue commands into the command buffer and go back to CPU-intensive rendering activities, leaving the GPU process to process them. We can make good use of both processes on multi-core machines as well as the GPU and CPU simultaneously thanks to this pipeline.

With that explanation out of the way, we can go back to explaining how the GL commands and resources are generated by the Renderer’s compositor.

Part 3: The Threaded Compositor

The compositor is implemented on top of the GL ES 2.0 client library which proxies the graphics calls to the GPU process (using the method explained above). When a page renders via the compositor, all of its pixels are drawn (remember, drawing != painting) directly into the window’s backbuffer via the GPU process.

The compositor’s architecture has evolved over time: initially it lived in the Renderer’s main thread, was then moved to its own thread (the so-called compositor thread), then took on additional responsibility orchestrating when paints occur (so-called impl-side painting). This document will focus on the latest version; see the GPU architecture roadmap for where older versions may still be in use.

In theory, the threaded compositor is fundamentally tasked with taking enough information from the main thread to produce frames independently in response to future user input, even if the main thread is busy and can’t be asked for additional data. In practice this currently means it makes a copy of the cc layer tree and SkPicture recordings for layer regions within in an area around the viewport’s current location.

Recording: Painting from Blink’s Perspective

The interest area is the region around the viewport for which SkPictures are recorded. When the DOM has changed, e.g. because the style of some elements are now different from the previous main-thread frame and have been invalidated, Blink paints the regions of invalidated layers within the interest area into an SkPicture-backed GraphicsContext. This doesn’t actually produce new pixels, rather it produces a display list of the Skia commands necessary to produce those new pixels. This display list will be used later to generate new pixels at the compositor’s discretion.

The Commit: Handoff to the Compositor Thread

The threaded compositor’s key property is operation on a copy of main thread state so it can produce frames without needing to ask the main thread for anything. There are accordingly two sides to the threaded compositor: the main-thread side, and the (poorly named) “impl” side, which is the compositor thread’s half. The main thread has a LayerTreeHost, which is its copy of the layer tree, and the impl thread has a LayerTreeHostImpl, which is its copy of the layer tree. Similar naming conventions are followed throughout.

Conceptually these two layer trees are completely separate, and the compositor (impl) thread’s copy can be used to produce frames without any interaction with the main thread. This means the main thread can be busy running JavaScript and the compositor can still be redraw previously-committed content on the GPU without interruption.

In order to produce interesting new frames, the compositor thread needs to know how it should modify its state (e.g. updating layer transforms in response to an event like a scroll). Hence, some input events (like scrolls) are forwarded from the Browser process to the compositor first and from there to the Renderer main thread. With input and output under its control, the threaded compositor can guarantee visual responsiveness to user input. In addition to scrolls, the compositor can perform any other page updates that don’t require asking Blink to repaint anything. Thus far CSS animations and CSS filters are the only other major compositor-driven page updates.

The two layer trees are kept synchronized by a series of messages known as the commit, mediated by the compositor’s scheduler (in cc/trees/thread_proxy.cc). The commit transfers the main thread’s state of the world to the compositor thread (including an updated layer tree, any new SkPicture recordings, etc), blocking the main thread so this synchronization can occur. It’s the final step during which the main thread is involved in production of a particular frame.

Running the compositor in its own thread allows the compositor’s copy of the layer tree to update the layer transform hierarchy without involving the main thread, but the main thread eventually needs e.g. the scroll offset information as well (so JavaScript can know where the viewport scrolled to, for example). Hence the commit is also responsible for applying any compositor-thread layer tree updates to the main thread’s tree and a few other tasks.

As an interesting aside, this architecture is the reason JavaScript touch event handlers prevent composited scrolls but scroll event handlers do not. JavaScript can call preventDefault() on a touch event, but not on a scroll event. So the compositor cannot scroll the page without first asking JavaScript (which runs on the main thread) if it would like to cancel an incoming touch event. Scroll events, on the other hand, can’t be prevented and are asynchronously delivered to JavaScript; hence the compositor thread can begin scrolling immediately regardless of whether or not the main thread processes the scroll event immediately.

Tree Activation

When the compositor thread gets a new layer tree from the main thread it examines the new tree to see what areas are invalid and re-rasterizes those layers. During this time the active tree remains the old layer tree the compositor thread had previously, and the pending tree is the new layer tree whose content is being rasterized.

To maintain consistency of the displayed content, the pending tree is only activated when its visible (i.e. within the viewport) high-resolution content is fully rasterized. Swapping from the current active tree to a now-ready pending tree is called activation. The net effect of waiting for the rastered content to be ready means the user can usually see at least some content, but that content might be stale. If no content is available Chrome displays a blank or checkerboard pattern with a GL shader instead.

It’s important to note that it’s possible to scroll past the rastered area of even the active tree, since Chrome only records SkPictures for layer regions within the interest area. If the user is scrolling toward an unrecorded area the compositor will ask the main thread to record and commit additional content, but if that new content can’t be recorded, committed, and rasterized to activate in time the user will scroll into a checkerboard zone.

To mitigate checkerboarding, Chrome can also quickly raster low-resolution content for the pending tree before high-resolution. Pending trees with only low-resolution content available for the viewport are activated if its better than what’s currently on screen (e.g. the outgoing active tree had no content at all rasterized for the current viewport). The tile manager (explained in the next section) decides what content to raster when.

This architecture isolates rasterization from the rest of the frame production flow. It enables a variety of technologies that improve the responsiveness of the graphics system. Image decode and resize operations are performed asynchronously, which were previously expensive main-thread operations performed during painting. The asynchronous texture upload system mentioned earlier in this document was introduced with impl-side painting as well.

Tiling

Rasterizing the entirety of every layer on the page is a waste of CPU time (for the paint operations) and memory (RAM for any software bitmaps the layer needs; VRAM for the texture storage). Instead of rasterizing the entire page, the compositor breaks up most web content layers into tiles and rasterizes layers on a per-tile basis.

Web content layer tiles are prioritized heuristically by a number of factors including the tile’s proximity to the viewport and its estimated time to being on-screen. GPU memory is then allocated to tiles based on their priority, and tiles are rastered from the SkPicture recordings to fill the available memory budget in priority order. Currently (May 2014) the specific approach to tile prioritization being reworked; see the Tile Prioritization Design Doc for more info.

Note that tiling isn’t necessary for layer types whose contents are already resident on the GPU, such as accelerated video or WebGL (for the curious, layer types are implemented in the cc/layers directory).

Rasterization: Painting from cc/Skia’s perspective

SkPicture records on the compositor thread get turned into bitmaps on the GPU in one of two ways: either painted by Skia’s software rasterizer into a bitmap and uploaded to the GPU as a texture, or painted by Skia’s OpenGL backend (Ganesh) directly into textures on the GPU.

For Ganesh-rasterized layers the SkPicture is played back with Ganesh and the resulting GL command stream gets handed to the GPU process via the command buffer. The GL command generation happens immediately when the compositor decides to rasterize any tiles, and tiles are bundled together to avoid prohibitive overhead of tiled rasterization on the GPU. See the GPU accelerated rasterization design doc for more information on the approach.

For software-rasterized layers the paint targets a bitmap in memory shared between the Renderer process and the GPU process. Bitmaps are handed to the GPU process via the resource transfer machinery described above. Because software rasterization can be very expensive, this rasterization doesn’t happen in the compositor thread itself (where it could block drawing a new frame for the active tree), but rather in a compositor raster worker thread. Multiple raster worker threads can be used to speed up software rasterization; each worker pulls from the front of the prioritized tile queue. Completed tiles are uploaded to the GPU as textures.

Texture uploads of bitmaps are a non-trivial bottleneck on memory-bandwidth-constrained platforms. This has handicapped the performance of software-rasterized layers, and continues to handicap uploads of bitmaps necessary for the hardware rasterizer (e.g. for image data or CPU-rendered masks). Chrome has had various different texture upload mechanisms in the past, but the most successful has been an asynchronous uploader that performs the upload in a worker thread in the GPU process (or an additional thread in the Browser process, in the case of Android. This prevents other operations from having to block on potentially-lengthy texture uploads.

One approach to removing the texture upload problem entirely would be to use zero-copy buffers shared between the the CPU and GPU on unified memory architecture devices exposing such primitives. Chrome does not currently use this construct, but could in the future; for more information see the GpuMemoryBuffer design doc.

Also note it’s possible to take third approach to how content is painted when using the GPU to rasterize: rasterize the content of each layer directly into the backbuffer at draw time, rather than into a texture beforehand. This has the advantage of memory savings (no intermediate texture) and some performance improvements (save a copy of the texture to the backbuffer when drawing), but has the downside of performance loss when the texture is effectively caching layer content (since now it needs to be re-painted every frame). This “direct to backbuffer” or “direct Ganesh” mode is not implemented as of May 2014, but see the GPU rasterization design doc for additional relevant considerations.

Compositing with the GPU process

**

Drawing on the GPU, Tiling, and Quads

Once all the textures are populated, rendering the contents of a page is simply a matter of doing a depth first traversal of the layer hierarchy and issuing a GL command to draw a texture for each layer into the frame buffer.

Drawing a layer on screen is really a matter of drawing each of its tiles. Tiles are represented as quads (simple 4-gons i.e. rectangles; see cc/quads) drawn filled with a subregion of the given layer’s content. The compositor generates quads and a set of render passes (render passes are simple data structures that hold a list of quads). The actual GL commands for drawing are generated separately from the quads (see cc/output/gl_renderer.cc). This is abstracted away from the quad implementation so it is possible to write non-GL backends for the compositor (the only significant non-GL implementation is the software compositor, covered later). Drawing the quads more or less amounts to setting up the viewport for each render pass, then setting up the transform for and drawing each quad in the render pass’s quad list.

Note that doing the traversal depth-first ensures proper z-ordering of cc layers, and the z-ordering of the potentially-multiple RenderLayers associated with that cc layer is guaranteed earlier by the ordering of the RenderObject tree traversal when the RenderObjects for a layer are painted.

Varied Scale Factors

One significant advantage of impl-side painting is that the compositor can reraster existing SkPictures at arbitrary scale factors. This comes in useful in two main contexts: pinch-to-zoom and producing low-resolution tiles during fast flings.

The compositor will intercept input events for pinch/zoom and scale the already-rastered tiles appropriately on the GPU, but it also rerasters at more suitable target resolutions while this is happening. Whenever the new tiles are ready (rastered and uploaded) they can be swapped in by activating the pending tree, improving the resolution of the pinch/zoom’d screen (even if the pinch isn’t yet complete).

When rasterizing in software the compositor also attempts to quickly produce low-resolution tiles (which are typically much cheaper to paint) and display them during a scroll if the high-res tiles aren’t yet ready. This is why some pages can look blurry during a fast scroll — the compositor displays the low-res tiles on screen while the high-res tiles raster.

From WebKit to the Screen

Software Rendering Architecture

Once all the RenderLayers are done painting into the shared bitmap the bitmap still needs to make it onto the screen. In Chrome, the bitmap resides in shared memory and control of it is passed to the Browser process via IPC. The Browser process is then responsible for drawing that bitmap in the appropriate tab / window via the OS’s windowing APIs (using e.g. the relevant HWND on Windows).