- Chapter 10 Define Errors Out Of Existence

- 10.1 Why exceptions add complexity

- 10.2 Too many exceptions

- 10.3 Define errors out of existence

- 10.4 Example: file deletion in Windows

- 10.5 Example: Java substring method

- 10.6 Mask exceptions

- 10.7 Exception aggregation

- 10.8 Just crash?

- 10.9 Design special cases out of existence

- 10.10 Taking it too far

- 10.11 Conclusion

Chapter 10 Define Errors Out Of Existence

Exception handling is one of the worst sources of complexity in software systems. Code that deals with special conditions is inherently harder to write than code that deals with normal cases, and developers often define exceptions without considering how they will be handled. This chapter discusses why exceptions contribute disproportionately to complexity, then it shows how to simplify exception handling. The key overall lesson from this chapter is to reduce the number of places where exceptions must be handled; in many cases the semantics of operations can be modified so that the normal behavior handles all situations and there is no exceptional condition to report (hence the title of this chapter).

10.1 Why exceptions add complexity

I use the term exception to refer to any uncommon condition that alters the normal flow of control in a program. Many programming languages include a formal exception mechanism that allows exceptions to be thrown by lower-level code and caught by enclosing code. However, exceptions can occur even without using a formal exception reporting mechanism, such as when a method returns a special value indicating that it didn’t complete its normal behavior. All of these forms of exceptions contribute to complexity.

A particular piece of code may encounter exceptions in several different ways:

- A caller may provide bad arguments or configuration information.

- An invoked method may not be able to complete a requested operation. For example, an I/O operation may fail, or a required resource may not be available.

- In a distributed system, network packets may be lost or delayed, servers may not respond in a timely fashion, or peers may communicate in unexpected ways.

- The code may detect bugs, internal inconsistencies, or situations it is not prepared to handle.

Large systems have to deal with many exceptional conditions, particularly if they are distributed or need to be fault-tolerant. Exception handling can account for a significant fraction of all the code in a system.

Exception handling code is inherently more difficult to write than normal-case code. An exception disrupts the normal flow of the code; it usually means that something didn’t work as expected. When an exception occurs, the programmer can deal with it in two ways, each of which can be complicated. The first approach is to move forward and complete the work in progress in spite of the exception. For example, if a network packet is lost, it can be resent; if data is corrupted, perhaps it can be recovered from a redundant copy. The second approach is to abort the operation in progress and report the exception upwards. However, aborting can be complicated because the exception may have occurred at a point where system state is inconsistent (a data structure might have been partially initialized); the exception handling code must restore consistency, such as by unwinding any changes made before the exception occurred.

Furthermore, exception handling code creates opportunities for more exceptions. Consider the case of resending a lost network packet. Perhaps the packet wasn’t actually lost, but was simply delayed. In this case, resending the packet will result in duplicate packets arriving at the peer; this introduces a new exceptional condition that the peer must handle. Or, consider the case of recovering lost data from a redundant copy: what if the redundant copy has also been lost? Secondary exceptions occurring during recovery are often more subtle and complex than the primary exceptions. If an exception is handled by aborting the operation in progress, then this must be reported to the caller as another exception. To prevent an unending cascade of exceptions, the developer must eventually find a way to handle exceptions without introducing more exceptions.

Language support for exceptions tends to be verbose and clunky, which makes exception handling code hard to read. For example, consider the following code, which reads a collection of tweets from a file using Java’s support for object serialization and deserialization:

try (FileInputStream fileStream = new FileInputStream(fileName);BufferedInputStream bufferedStream = new BufferedInputStream(fileStream);ObjectInputStream objectStream = new ObjectInputStream(bufferedStream);) {for (int i = 0; i < tweetsPerFile; i++) {tweets.add((Tweet) objectStream.readObject());}}catch (FileNotFoundException e) {...}catch (ClassNotFoundException e) {...}catch (EOFException e) {// Not a problem: not all tweet files have full// set of tweets.}catch (IOException e) {...}catch (ClassCastException e) {...}

Just the basic try-catch boilerplate accounts for more lines of code than the code for normal-case operation, without even considering the code that actually handles the exceptions. It is hard to relate the exception handling code to the normal-case code: for example, it’s not obvious where each exception is generated. An alternative approach is to break up the code into many distinct try blocks; in the extreme case there could be a try for each line of code that can generate an exception. This would make it clear where exceptions occur, but the try blocks themselves break up the flow of the code and make it harder to read; in addition, some exception handling code might end up duplicated in multiple try blocks.

It’s difficult to ensure that exception handling code really works. Some exceptions, such as I/O errors, can’t easily be generated in a test environment, so it’s hard to test the code that handles them. Exceptions don’t occur very often in running systems, so exception handling code rarely executes. Bugs can go undetected for a long time, and when the exception handling code is finally needed, there’s a good chance that it won’t work (one of my favorite sayings: “code that hasn’t been executed doesn’t work”). A recent study found that more than 90% of catastrophic failures in distributed data-intensive systems were caused by incorrect error handling1. When exception handling code fails, it’s difficult to debug the problem, since it occurs so infrequently.

10.2 Too many exceptions

Programmers exacerbate the problems related to exception handling by defining unnecessary exceptions. Most programmers are taught that it’s important to detect and report errors; they often interpret this to mean “the more errors detected, the better.” This leads to an over-defensive style where anything that looks even a bit suspicious is rejected with an exception, which results in a proliferation of unnecessary exceptions that increase the complexity of the system.

I made this mistake myself in the design of the Tcl scripting language. Tcl contains an unset command that can be used to remove a variable. I defined unset so that it throws an error if the variable doesn’t exist. At the time I thought that it must be a bug if someone tries to delete a variable that doesn’t exist, so Tcl should report it. However, one of the most common uses of unset is to clean up temporary state created by some previous operation. It’s often hard to predict exactly what state was created, particularly if the operation aborted partway through. Thus, the simplest thing is to delete all of the variables that might possibly have been created. The definition of unset makes this awkward: developers end up enclosing calls to unset in catch statements to catch and ignore errors thrown by unset. In retrospect, the definition of the unset command is one of the biggest mistakes I made in the design of Tcl.

It’s tempting to use exceptions to avoid dealing with difficult situations: rather than figuring out a clean way to handle it, just throw an exception and punt the problem to the caller. Some might argue that this approach empowers callers, since it allows each caller to handle the exception in a different way. However, if you are having trouble figuring out what to do for the particular situation, there’s a good chance that the caller won’t know what to do either. Generating an exception in a situation like this just passes the problem to someone else and adds to the system’s complexity.

The exceptions thrown by a class are part of its interface; classes with lots of exceptions have complex interfaces, and they are shallower than classes with fewer exceptions. An exception is a particularly complex element of an interface. It can propagate up through several stack levels before being caught, so it affects not just the method’s caller, but potentially also higher-level callers (and their interfaces).

Throwing exceptions is easy; handling them is hard. Thus, the complexity of exceptions comes from the exception handling code. The best way to reduce the complexity damage caused by exception handling is to reduce the number of places where exceptions have to be handled. The rest of this chapter will discuss four techniques for reducing the number of exception handlers.

10.3 Define errors out of existence

The best way to eliminate exception handling complexity is to define your APIs so that there are no exceptions to handle: define errors out of existence. This may seem sacrilegious, but it is very effective in practice. Consider the Tcl unset command discussed above. Rather than throwing an error when unset is asked to delete an unknown variable, it should have simply returned without doing anything. I should have changed the definition of unset slightly: rather than deleting a variable, unset should ensure that a variable no longer exists. With the first definition, unset can’t do its job if the variable doesn’t exist, so generating an exception makes sense. With the second definition, it is perfectly natural for unset to be invoked with the name of a variable that doesn’t exist. In this case, its work is already done, so it can simply return. There is no longer an error case to report.

10.4 Example: file deletion in Windows

File deletion provides another example of how errors can be defined away. The Windows operating system does not permit a file to be deleted if it is open in a process. This is a continual source of frustration for developers and users. In order to delete a file that is in use, the user must search through the system to find the process that has the file open, and then kill that process. Sometimes users give up and reboot their system, just so they can delete a file.

The Unix operating system defines file deletion more elegantly. In Unix, if a file is open when it is deleted, Unix does not delete the file immediately. Instead, it marks the file for deletion, then the delete operation returns successfully. The file name has been removed from its directory, so no other processes can open the old file and a new file with the same name can be created, but the existing file data persists. Processes that already have the file open can continue to read it and write it normally. Once the file has been closed by all of the accessing processes, its data is freed.

The Unix approach defines away two different kinds of errors. First, the delete operation no longer returns an error if the file is currently in use; the delete succeeds, and the file will eventually be deleted. Second, deleting a file that’s in use does not create exceptions for the processes using the file. One possible approach to this problem would have been to delete the file immediately and mark all of the opens of the file to disable them; any attempts by other processes to read or write the deleted file would fail. However, this approach would create new errors for those processes to handle. Instead, Unix allows them to keep accessing the file normally; delaying the file deletion defines errors out of existence.

It may seem strange that Unix allows a process to continue to read and write a doomed file, but I have never encountered a situation where this caused significant problems. The Unix definition of file deletion is much simpler to work with, both for developers and users, than the Windows definition.

10.5 Example: Java substring method

As a final example, consider the Java String class and its substring method. Given two indexes into a string, substring returns the substring starting at the character given by the first index and ending with the character just before the second index. However, if either index is outside the range of the string, then substring throws IndexOutOfBoundsException. This exception is unnecessary and complicates the use of this method. I often find myself in a situation where one or both of the indices may be outside the range of the string, and I would like to extract all of the characters in the string that overlap the specified range. Unfortunately, this requires me to check each of the indices and round them up to zero or down to the end of the string; a one-line method call now becomes 5–10 lines of code.

The Java substring method would be easier to use if it performed this adjustment automatically, so that it implemented the following API: “returns the characters of the string (if any) with index greater than or equal to beginIndex and less than endIndex.” This is a simple and natural API, and it defines the IndexOutOfBoundsException exception out of existence. The method’s behavior is now well-defined even if one or both of the indexes are negative, or if beginIndex is greater than endIndex. This approach simplifies the API for the method while increasing its functionality, so it makes the method deeper. Many other languages have taken the error-free approach; for example, Python returns an empty result for out-of-range list slices.

When I argue for defining errors out of existence, people sometimes counter that throwing errors will catch bugs; if errors are defined out of existence, won’t that result in buggier software? Perhaps this is why the Java developers decided that substring should throw exceptions. The error-ful approach may catch some bugs, but it also increases complexity, which results in other bugs. In the error-ful approach, developers must write additional code to avoid or ignore the errors, and this increases the likelihood of bugs; or, they may forget to write the additional code, in which case unexpected errors may be thrown at runtime. In contrast, defining errors out of existence simplifies APIs and it reduces the amount of code that must be written.

Overall, the best way to reduce bugs is to make software simpler.

10.6 Mask exceptions

The second technique for reducing the number of places where exceptions must be handled is exception masking. With this approach, an exceptional condition is detected and handled at a low level in the system, so that higher levels of software need not be aware of the condition. Exception masking is particularly common in distributed systems. For instance, in a network transport protocol such as TCP, packets can be dropped for various reasons such as corruption and congestion. TCP masks packet loss by resending lost packets within its implementation, so all data eventually gets through and clients are unaware of the dropped packets.

A more controversial example of masking occurs in the NFS network file system. If an NFS file server crashes or fails to respond for any reason, clients reissue their requests to the server over and over again until the problem is eventually resolved. The low-level file system code on the client does not report any exceptions to the invoking application. The operation in progress (and hence the application) just hangs until the operation can complete successfully. If the hang lasts more than a short time, the NFS client prints messages on the user’s console of the form “NFS server xyzzy not responding still trying.”

NFS users often complain about the fact that their applications hang while waiting for an NFS server to resume normal operation. Many people have suggested that NFS should abort operations with an exception rather than hanging. However, reporting exceptions would make things worse, not better. There’s not much an application can do if it loses access to its files. One possibility would be for the application to retry the file operation, but this would still hang the application, and it’s easier to perform the retry in one place in the NFS layer, rather than at every file system call in every application (a compiler shouldn’t have to worry about this!). The other alternative is for applications to abort and return errors to their callers. It’s unlikely that the callers would know what to do either, so they would abort as well, resulting in a collapse of the user’s working environment. Users still wouldn’t be able to get any work done while the file server was down, and they would have to restart all of their applications once the file server came back to life.

Thus, the best alternative is for NFS to mask the errors and hang applications. With this approach, applications don’t need any code to deal with server problems, and they can resume seamlessly once the server comes back to life. If users get tired of waiting, they can always abort applications manually.

Exception masking doesn’t work in all situations, but it is a powerful tool in the situations where it works. It results in deeper classes, since it reduces the class’s interface (fewer exceptions for users to be aware of) and adds functionality in the form of the code that masks the exception. Exception masking is an example of pulling complexity downward.

10.7 Exception aggregation

The third technique for reducing complexity related to exceptions is exception aggregation. The idea behind exception aggregation is to handle many exceptions with a single piece of code; rather than writing distinct handlers for many individual exceptions, handle them all in one place with a single handler.

Consider how to handle missing parameters in a Web server. A Web server implements a collection of URLs. When the server receives an incoming URL, it dispatches to a URL-specific service method to process that URL and generate a response. The URL contains various parameters that are used to generate the response. Each service method will call a lower-level method (let’s call it getParameter) to extract the parameters that it needs from the URL. If the URL does not contain the desired parameter, getParameter throws an exception.

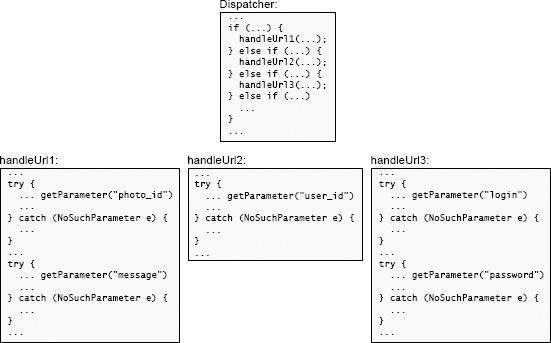

When students in a software design class implemented such a server, many of them wrapped each distinct call to getParameter in a separate exception handler to catch NoSuchParameter exceptions, as in Figure 10.1. This resulted in a large number of handlers, all of which did essentially the same thing (generate an error response).

Figure 10.1: The code at the top dispatches to one of several methods in a Web server, each of which handles a particular URL. Each of those methods (bottom) uses parameters from the incoming HTTP request. In this figure, there is a separate exception handler for each call to getParameter; this results in duplicated code.

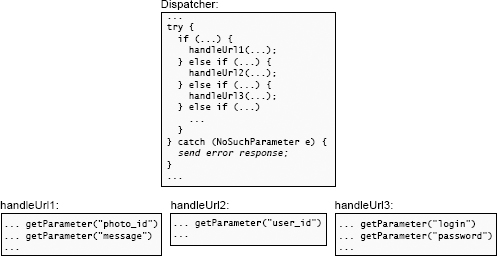

A better approach is to aggregate the exceptions. Instead of catching the exceptions in the individual service methods, let them propagate up to the top-level dispatch method for the Web server, as in Figure 10.2. A single handler in this method can catch all of the exceptions and generate an appropriate error response for missing parameters.

The aggregation approach can be taken even further in the Web example. There are many other errors besides missing parameters that can occur while processing a Web page; for example, a parameter might not have the right syntax (the service method expected an integer, but the value was “xyz”), or the user might not have permission for the requested operation. In each case, the error should result in an error response; the errors differ only in the error message to include in the response (“parameter ‘quantity’ not present in URL” or “bad value ‘xyz’ for ‘quantity’ parameter; must be positive integer”). Thus, all conditions resulting in an error response can be handled with a single top-level exception handler. The error message can be generated at the time the exception is thrown and included as a variable in the exception record; for example, getParameter will generate the “parameter ‘quantity’ not present in URL” message. The top-level handler extracts the message from the exception and incorporates it into the error response.

Figure 10.2: This code is functionally equivalent to Figure 10.1, but exception handling has been aggregated: a single exception handler in the dispatcher catches all of the NoSuchParameter exceptions from all of the URL-specific methods.

The aggregation described in the preceding paragraph has good properties from the standpoint of encapsulation and information hiding. The top-level exception handler encapsulates knowledge about how to generate error responses, but it knows nothing about specific errors; it just uses the error message provided in the exception. The getParameter method encapsulates knowledge about how to extract a parameter from a URL, and it also knows how to describe extraction errors in a human-readable form. These two pieces of information are closely related, so it makes sense for them to be in the same place. However, getParameter knows nothing about the syntax of an HTTP error response. As new functionality is added to the Web server, new methods like getParameter may be created with their own errors. If the new methods throw exceptions in the same way as getParameter (by generating exceptions that inherit from the same superclass and including an error message in each exception), they can plug into the existing system with no other changes: the top-level handler will automatically generate error responses for them.

This example illustrates a generally-useful design pattern for exception handling. If a system processes a series of requests, it’s useful to define an exception that aborts the current request, cleans up the system’s state, and continues with the next request. The exception is caught in a single place near the top of the system’s request-handling loop. This exception can be thrown at any point in the processing of a request to abort the request; different subclasses of the exception can be defined for different conditions. Exceptions of this type should be clearly distinguished from exceptions that are fatal to the entire system.

Exception aggregation works best if an exception propagates several levels up the stack before it is handled; this allows more exceptions from more methods to be handled in the same place. This is the opposite of exception masking: masking usually works best if an exception is handled in a low-level method. For masking, the low-level method is typically a library method used by many other methods, so allowing the exception to propagate would increase the number of places where it is handled. Masking and aggregation are similar in that both approaches position an exception handler where it can catch the most exceptions, eliminating many handlers that would otherwise need to be created.

Another example of exception aggregation occurs in the RAMCloud storage system for crash recovery. A RAMCloud system consists of a collection of storage servers that keep multiple copies of each object, so the system can recover from a variety of failures. For example, if a server crashes and loses all of its data, RAMCloud reconstructs the lost data using copies stored on other servers. Errors can also happen on a smaller scale; for example, a server may discover that an individual object is corrupted.

RAMCloud does not have separate recovery mechanisms for each different kind of error. Instead, RAMCloud “promotes” many smaller errors into larger ones. RAMCloud could, in principle, handle a corrupted object by restoring that one object from a backup copy. However, it doesn’t do this. Instead, if it discovers a corrupted object it crashes the server containing the object. RAMCloud uses this approach because crash recovery is quite complex and this approach minimized the number of different recovery mechanisms that had to be created. Creating a recovery mechanism for crashed servers was unavoidable, so RAMCloud uses the same mechanism for other kinds of recovery as well. This reduced the amount of code that had to be written, and it also meant that server crash recovery gets invoked more often. As a result, bugs in recovery are more likely to be discovered and fixed.

One disadvantage of promoting a corrupted object into a server crash is that it increases the cost of recovery considerably. This is not a problem in RAMCloud, since object corruption is quite rare. However, error promotion may not make sense for errors that happen frequently. As one example, it would not be practical to crash a server anytime one of its network packets is lost.

One way of thinking about exception aggregation is that it replaces several special-purpose mechanisms, each tailored for a particular situation, with a single general-purpose mechanism that can handle multiple situations. This provides another illustration of the benefits of general-purpose mechanisms.

10.8 Just crash?

The fourth technique for reducing complexity related to exception handling is to crash the application. In most applications there will be certain errors that it’s not worth trying to handle. Typically, these errors are difficult or impossible to handle and don’t occur very often. The simplest thing to do in response to these errors is to print diagnostic information and then abort the application.

One example is “out of memory” errors that occur during storage allocation. Consider the malloc function in C, which returns NULL if it cannot allocate the desired block of memory. This is an unfortunate behavior, because it assumes that every single caller of malloc will check the return value and take appropriate action if there is no memory. Applications contain numerous calls to malloc, so checking the result after each call would add significant complexity. If a programmer forgets the check (which is fairly likely), then the application will dereference a null pointer if memory runs out, resulting in a crash that camouflages the real problem.

Furthermore, there isn’t much an application can do when it discovers that memory is exhausted. In principle the application could look for unneeded memory to free, but if the application had unneeded memory it could already have freed it, which would have prevented the out-of-memory error in the first place. Today’s systems have so much memory that memory almost never runs out; if it does, it usually indicates a bug in the application. Thus, it rarely make sense to try to handle out-of-memory errors; this creates too much complexity for too little benefit.

A better approach is to define a new method ckalloc, which calls malloc, checks the result, and aborts the application with an error message if memory is exhausted. The application never invokes malloc directly; it always invokes ckalloc.

In newer languages such as C++ and Java, the new operator throws an exception if memory is exhausted. There’s not much point in catching this exception, since there’s a good chance that the exception handler will also try to allocate memory, which will also fail. Dynamically allocated memory is such a fundamental element of any modern application that it doesn’t make sense for the application to continue if memory is exhausted; it’s better to crash as soon as the error is detected.

There are many other examples of errors where crashing the application makes sense. For most programs, if an I/O error occurs while reading or writing an open file (such as a disk hard error), or if a network socket cannot be opened, there’s not much the application can do to recover, so aborting with a clear error message is a sensible approach. These errors are infrequent, so they are unlikely to affect the overall usability of the application. Aborting with an error message is also appropriate if an application encounters an internal error such as an inconsistent data structure. Conditions like this probably indicate bugs in the program.

Whether or not it is acceptable to crash on a particular error depends on the application. For a replicated storage system, it isn’t appropriate to abort on an I/O error. Instead, the system must use replicated data to recover any information that was lost. The recovery mechanisms will add considerable complexity to the program, but recovering lost data is an essential part of the value the system provides to its users.

10.9 Design special cases out of existence

For the same reason that it makes sense to define errors out of existence, it also makes sense to define other special cases out of existence. Special cases can result in code that is riddled with if statements, which make the code hard to understand and lead to bugs. Thus, special cases should be eliminated wherever possible. The best way to do this is by designing the normal case in a way that automatically handles the special cases without any extra code.

In the text editor project described in Chapter 6, students had to implement a mechanism for selecting text and copying or deleting the selection. Most students introduced a state variable in their selection implementation to indicate whether or not the selection exists. They probably chose this approach because there are times when no selection is visible on the screen, so it seemed natural to represent this notion in the implementation. However, this approach resulted in numerous checks to detect the “no selection” condition and handle it specially.

The selection handling code can be simplified by eliminating the “no selection” special case, so that the selection always exists. When there is no selection visible on the screen, it can be represented internally with an empty selection, whose starting and ending positions are the same. With this approach, the selection management code can be written without any checks for “no selection”. When copying the selection, if the selection is empty then 0 bytes will be inserted at the new location (if implemented correctly, there will be no need to check for 0 bytes as a special case). Similarly, it should be possible to design the code for deleting the selection so that the empty case is handled without any special-case checks. Consider a selection all on a single line. To delete the selection, extract the portion of the line preceding the selection and concatenate it with the portion of the line following the selection to form the new line. If the selection is empty, this approach will regenerate the original line.

This example also illustrates the “different layer, different abstraction” idea from Chapter 7. The notion of “no selection” makes sense in terms of how the user thinks about the application’s interface, but that doesn’t mean it has to be represented explicitly inside the application. Having a selection that always exists, but is sometimes empty and thus invisible, results in a simpler implementation.

10.10 Taking it too far

Defining away exceptions, or masking them inside a module, only makes sense if the exception information isn’t needed outside the module. This was true for the examples in this chapter, such the Tcl unset command and the Java substring method; in the rare situations where a caller cares about the special cases detected by the exceptions, there are other ways for it to get this information.

However, it is possible to take this idea too far. In a module for network communication, a student team masked all network exceptions: if a network error occurred, the module caught it, discarded it, and continued as if there were no problem. This meant that applications using the module had no way to find out if messages were lost or a peer server failed; without this information, it was impossible to build robust applications. In this case, it is essential for the module to expose the exceptions, even though they add complexity to the module’s interface.

With exceptions, as with many other areas in software design, you must determine what is important and what is not important. Things that are not important should be hidden, and the more of them the better. But when something is important, it must be exposed.

10.11 Conclusion

Special cases of any form make code harder to understand and increase the likelihood of bugs. This chapter focused on exceptions, which are one of the most significant sources of special-case code, and discussed how to reduce the number of places where exceptions must be handled. The best way to do this is by redefining semantics to eliminate error conditions. For exceptions that can’t be defined away, you should look for opportunities to mask them at a low level, so their impact is limited, or aggregate several special-case handlers into a single more generic handler. Together, these techniques can have a significant impact on overall system complexity.

1Ding Yuan et. al., “Simple Testing Can Prevent Most Critical Failures: An Analysis of Production Failures in Distributed Data-Intensive Systems,” 2014 USENIX Conference on Operating System Design and Implementation.