Chapter 4 Modules Should Be Deep

One of the most important techniques for managing software complexity is to design systems so that developers only need to face a small fraction of the overall complexity at any given time. This approach is called modular design, and this chapter presents its basic principles.

4.1 Modular design

In modular design, a software system is decomposed into a collection of modules that are relatively independent. Modules can take many forms, such as classes, subsystems, or services. In an ideal world, each module would be completely independent of the others: a developer could work in any of the modules without knowing anything about any of the other modules. In this world, the complexity of a system would be the complexity of its worst module.

Unfortunately, this ideal is not achievable. Modules must work together by calling each others’s functions or methods. As a result, modules must know something about each other. There will be dependencies between the modules: if one module changes, other modules may need to change to match. For example, the arguments for a method create a dependency between the method and any code that invokes the method. If the required arguments change, all invocations of the method must be modified to conform to the new signature. Dependencies can take many other forms, and they can be quite subtle. The goal of modular design is to minimize the dependencies between modules.

In order to manage dependencies, we think of each module in two parts: an interface and an implementation. The interface consists of everything that a developer working in a different module must know in order to use the given module. Typically, the interface describes what the module does but not how it does it. The implementation consists of the code that carries out the promises made by the interface. A developer working in a particular module must understand the interface and implementation of that module, plus the interfaces of any other modules invoked by the given module. A developer should not need to understand the implementations of modules other than the one he or she is working in.

Consider a module that implements balanced trees. The module probably contains sophisticated code for ensuring that the tree remains balanced. However, this complexity is not visible to users of the module. Users see a relatively simple interface for invoking operations to insert, remove, and fetch nodes in the tree. To invoke an insert operation, the caller need only provide the key and value for the new node; the mechanisms for traversing the tree and splitting nodes are not visible in the interface.

For the purposes of this book, a module is any unit of code that has an interface and an implementation. Each class in an object-oriented programming language is a module. Methods within a class, or functions in a language that isn’t object-oriented, can also be thought of as modules: each of these has an interface and an implementation, and modular design techniques can be applied to them. Higher-level subsystems and services are also modules; their interfaces may take different forms, such as kernel calls or HTTP requests. Much of the discussion about modular design in this book focuses on designing classes, but the techniques and concepts apply to other kinds of modules as well.

The best modules are those whose interfaces are much simpler than their implementations. Such modules have two advantages. First, a simple interface minimizes the complexity that a module imposes on the rest of the system. Second, if a module is modified in a way that does not change its interface, then no other module will be affected by the modification. If a module’s interface is much simpler than its implementation, there will be many aspects of the module that can be changed without affecting other modules.

4.2 What’s in an interface??

The interface to a module contains two kinds of information: formal and informal. The formal parts of an interface are specified explicitly in the code, and some of these can be checked for correctness by the programming language. For example, the formal interface for a method is its signature, which includes the names and types of its parameters, the type of its return value, and information about exceptions thrown by the method. Most programming languages ensure that each invocation of a method provides the right number and types of arguments to match its signature. The formal interface for a class consists of the signatures for all of its public methods, plus the names and types of any public variables.

Each interface also includes informal elements. These are not specified in a way that can be understood or enforced by the programming language. The informal parts of an interface include its high-level behavior, such as the fact that a function deletes the file named by one of its arguments. If there are constraints on the usage of a class (perhaps one method must be called before another), these are also part of the class’s interface. In general, if a developer needs to know a particular piece of information in order to use a module, then that information is part of the module’s interface. The informal aspects of an interface can only be described using comments, and the programming language cannot ensure that the description is complete or accurate1. For most interfaces the informal aspects are larger and more complex than the formal aspects.

One of the benefits of a clearly specified interface is that it indicates exactly what developers need to know in order to use the associated module. This helps to eliminate the “unknown unknowns” problem described in Section 2.2.

4.3 Abstractions

The term abstraction is closely related to the idea of modular design. An abstraction is a simplified view of an entity, which omits unimportant details. Abstractions are useful because they make it easier for us to think about and manipulate complex things.

In modular programming, each module provides an abstraction in form of its interface. The interface presents a simplified view of the module’s functionality; the details of the implementation are unimportant from the standpoint of the module’s abstraction, so they are omitted from the interface.

In the definition of abstraction, the word “unimportant” is crucial. The more unimportant details that are omitted from an abstraction, the better. However, a detail can only be omitted from an abstraction if it is unimportant. An abstraction can go wrong in two ways. First, it can include details that are not really important; when this happens, it makes the abstraction more complicated than necessary, which increases the cognitive load on developers using the abstraction. The second error is when an abstraction omits details that really are important. This results in obscurity: developers looking only at the abstraction will not have all the information they need to use the abstraction correctly. An abstraction that omits important details is a false abstraction: it might appear simple, but in reality it isn’t. The key to designing abstractions is to understand what is important, and to look for designs that minimize the amount of information that is important.

As an example, consider a file system. The abstraction provided by a file system omits many details, such as the mechanism for choosing which blocks on a storage device to use for the data in a given file. These details are unimportant to users of the file system (as long as the system provides adequate performance). However, some of the details of a file system’s implementation are important to users. Most file systems cache data in main memory, and they may delay writing new data to the storage device in order to improve performance. Some applications, such as databases, need to know exactly when data is written through to storage, so they can ensure that data will be preserved after system crashes. Thus, the rules for flushing data to secondary storage must be visible in the file system’s interface.

We depend on abstractions to manage complexity not just in programming, but pervasively in our everyday lives. A microwave oven contains complex electronics to convert alternating current into microwave radiation and distribute that radiation throughout the cooking cavity. Fortunately, users see a much simpler abstraction, consisting of a few buttons to control the timing and intensity of the microwaves. Cars provide a simple abstraction that allows us to drive them without understanding the mechanisms for electrical motors, battery power management, anti-lock brakes, cruise control, and so on.

4.4 Deep modules

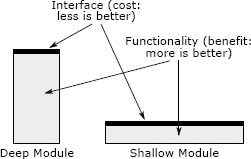

The best modules are those that provide powerful functionality yet have simple interfaces. I use the term deep to describe such modules. To visualize the notion of depth, imagine that each module is represented by a rectangle, as shown in Figure 4.1. The area of each rectangle is proportional to the functionality implemented by the module. The top edge of a rectangle represents the module’s interface; the length of that edge indicates the complexity of the interface. The best modules are deep: they have a lot of functionality hidden behind a simple interface. A deep module is a good abstraction because only a small fraction of its internal complexity is visible to its users.

Figure 4.1: Deep and shallow modules. The best modules are deep: they allow a lot of functionality to be accessed through a simple interface. A shallow module is one with a relatively complex interface, but not much functionality: it doesn’t hide much complexity.

Module depth is a way of thinking about cost versus benefit. The benefit provided by a module is its functionality. The cost of a module (in terms of system complexity) is its interface. A module’s interface represents the complexity that the module imposes on the rest of the system: the smaller and simpler the interface, the less complexity that it introduces. The best modules are those with the greatest benefit and the least cost. Interfaces are good, but more, or larger, interfaces are not necessarily better!

The mechanism for file I/O provided by the Unix operating system and its descendants, such as Linux, is a beautiful example of a deep interface. There are only five basic system calls for I/O, with simple signatures:

int open(const char* path, int flags, mode_t permissions);ssize_t read(int fd, void* buffer, size_t count);ssize_t write(int fd, const void* buffer, size_t count);off_t lseek(int fd, off_t offset, int referencePosition);int close(int fd);

The open system call takes a hierarchical file name such as /a/b/c and returns an integer file descriptor, which is used to reference the open file. The other arguments for open provide optional information such as whether the file is being opened for reading or writing, whether a new file should be created if there is no existing file, and access permissions for the file, if a new file is created. The read and write system calls transfer information between buffer areas in the application’s memory and the file; close ends the access to the file. Most files are accessed sequentially, so that is the default; however, random access can be achieved by invoking the lseek system call to change the current access position.

A modern implementation of the Unix I/O interface requires hundreds of thousands of lines of code, which address complex issues such as:

- How are files represented on disk in order to allow efficient access?

- How are directories stored, and how are hierarchical path names processed to find the files they refer to?

- How are permissions enforced, so that one user cannot modify or delete another user’s files?

- How are file accesses implemented? For example, how is functionality divided between interrupt handlers and background code, and how do these two elements communicate safely?

- What scheduling policies are used when there are concurrent accesses to multiple files?

- How can recently accessed file data be cached in memory in order to reduce the number of disk accesses?

- How can a variety of different secondary storage devices, such as disks and flash drives, be incorporated into a single file system?

All of these issues, and many more, are handled by the Unix file system implementation; they are invisible to programmers who invoke the system calls. Implementations of the Unix I/O interface have evolved radically over the years, but the five basic kernel calls have not changed.

Another example of a deep module is the garbage collector in a language such as Go or Java. This module has no interface at all; it works invisibly behind the scenes to reclaim unused memory. Adding garbage collection to a system actually shrinks its overall interface, since it eliminates the interface for freeing objects. The implementation of a garbage collector is quite complex, but that complexity is hidden from programmers using the language.

Deep modules such as Unix I/O and garbage collectors provide powerful abstractions because they are easy to use, yet they hide significant implementation complexity.

4.5 Shallow modules

On the other hand, a shallow module is one whose interface is relatively complex in comparison to the functionality that it provides. For example, a class that implements linked lists is shallow. It doesn’t take much code to manipulate a linked list (inserting or deleting an element takes only a few lines), so the linked list abstraction doesn’t hide very many details. The complexity of a linked list interface is nearly as great as the complexity of its implementation. Shallow classes are sometimes unavoidable, but they don’t provide help much in managing complexity.

Here is an extreme example of a shallow method, taken from a project in a software design class:

private void addNullValueForAttribute(String attribute) {data.put(attribute, null);}

From the standpoint of managing complexity, this method makes things worse, not better. The method offers no abstraction, since all of its functionality is visible through its interface. For example, callers probably need to know that the attribute will be stored in the data variable. It is no simpler to think about the interface than to think about the full implementation. If the method is documented properly, the documentation will be longer than the method’s code. It even takes more keystrokes to invoke the method than it would take for a caller to manipulate the data variable directly. The method adds complexity (in the form of a new interface for developers to learn) but provides no compensating benefit.

img Red Flag: Shallow Module img

A shallow module is one whose interface is complicated relative to the functionality it provides. Shallow modules don’t help much in the battle against complexity, because the benefit they provide (not having to learn about how they work internally) is negated by the cost of learning and using their interfaces. Small modules tend to be shallow.

4.6 Classitis

Unfortunately, the value of deep classes is not widely appreciated today. The conventional wisdom in programming is that classes should be small, not deep. Students are often taught that the most important thing in class design is to break up larger classes into smaller ones. The same advice is often given about methods: “Any method longer than N lines should be divided into multiple methods” (N can be as low as 10). This approach results in large numbers of shallow classes and methods, which add to overall system complexity.

The extreme of the “classes should be small” approach is a syndrome I call classitis, which stems from the mistaken view that “classes are good, so more classes are better.” In systems suffering from classitis, developers are encouraged to minimize the amount of functionality in each new class: if you want more functionality, introduce more classes. Classitis may result in classes that are individually simple, but it increases the complexity of the overall system. Small classes don’t contribute much functionality, so there have to be a lot of them, each with its own interface. These interfaces accumulate to create tremendous complexity at the system level. Small classes also result in a verbose programming style, due to the boilerplate required for each class.

4.7 Examples: Java and Unix I/O

One of the most visible examples of classitis today is the Java class library. The Java language doesn’t require lots of small classes, but a culture of classitis seems to have taken root in the Java programming community. For example, to open a file in order to read serialized objects from it, you must create three different objects:

FileInputStream fileStream = new FileInputStream(fileName);BufferedInputStream bufferedStream = new BufferedInputStream(fileStream);ObjectInputStream objectStream = new ObjectInputStream(bufferedStream);

A FileInputStream object provides only rudimentary I/O: it is not capable of performing buffered I/O, nor can it read or write serialized objects. The BufferedInputStream object adds buffering to a FileInputStream, and the ObjectInputStream adds the ability to read and write serialized objects. The first two objects in the code above, fileStream and bufferedStream, are never used once the file has been opened; all future operations use objectStream.

It is particularly annoying (and error-prone) that buffering must be requested explicitly by creating a separate BufferedInputStream object; if a developer forgets to create this object, there will be no buffering and I/O will be slow. Perhaps the Java developers would argue that not everyone wants to use buffering for file I/O, so it shouldn’t be built into the base mechanism. They might argue that it’s better to keep buffering separate, so people can choose whether or not to use it. Providing choice is good, but interfaces should be designed to make the common case as simple as possible (see the formula on page 6). Almost every user of file I/O will want buffering, so it should be provided by default. For those few situations where buffering is not desirable, the library can provide a mechanism to disable it. Any mechanism for disabling buffering should be cleanly separated in the interface (for example, by providing a different constructor for FileInputStream, or through a method that disables or replaces the buffering mechanism), so that most developers do not even need to be aware of its existence.

In contrast, the designers of the Unix system calls made the common case simple. For example, they recognized that sequential I/O is most common, so they made that the default behavior. Random access is still relatively easy to do, using the lseek system call, but a developer doing only sequential access need not be aware of that mechanism. If an interface has many features, but most developers only need to be aware of a few of them, the effective complexity of that interface is just the complexity of the commonly used features.

4.8 Conclusion

By separating the interface of a module from its implementation, we can hide the complexity of the implementation from the rest of the system. Users of a module need only understand the abstraction provided by its interface. The most important issue in designing classes and other modules is to make them deep, so that they have simple interfaces for the common use cases, yet still provide significant functionality. This maximizes the amount of complexity that is concealed.

1There exist languages, mostly in the research community, where the overall behavior of a method or function can be described formally using a specification language. The specification can be checked automatically to ensure that it matches the implementation. An interesting question is whether such a formal specification could replace the informal parts of an interface. My current opinion is that an interface described in English is likely to be more intuitive and understandable for developers than one written in a formal specification language.