JavaScript is cool (don’t @ me), but how can a machine actually understand the code you’ve written? As JavaScript devs, we usually don’t have to deal with compilers ourselves. However, it’s definitely good to know the basics of the JavaScript engine and see how it handles our human-friendly JS code, and turns it into something machines understand! 🥳

| Note: This post is mainly based on the V8 engine used by Node.js and Chromium-based browsers.

The HTML parser encounters a script tag with a source. Code from this source gets loaded from either the network, cache, or an installed service worker. The response is the requested script as a stream of bytes, which the byte stream decoder takes care of! The byte stream decoder decodes the stream of bytes as it’s being downloaded.

The byte stream decoder creates tokens from the decoded stream of bytes. For example, 0066 decodes to f, 0075 to u, 006e to n, 0063 to c, 0074 to t, 0069 to i, 006f to o, and 006e to n followed by a white space. Seems like you wrote function! This is a reserved keyword in JavaScript, a token gets created, and sent to the parser (and pre-parser, which I didn’t cover in the gifs but will explain later). The same happens for the rest of the byte stream.

The engine uses two parsers: the pre-parser, and the parser. The pre-parser only checks the tokens early to see if there are any syntactical errors ❌. This can reduce the amount it takes to spot errors in the code, which otherwise would’ve been discovered later by the parser!

If there are no errors, the parser creates nodes based on the tokens it receives from the byte stream decoder. With these nodes, it creates an Abstract Syntax Tree, or AST. 🌳

Next, it’s time for the interpreter! The interpreter which walks through the AST, and generates byte code based on the information that the AST contains. Once the byte code has been generated fully, the AST is deleted, clearing up memory space. Finally, we have something that a machine can work with! 🎉

Although byte code is fast, it can be faster. As this bytecode runs, information is being generated. It can detect whether certain behavior happens often, and the types of the data that’s been used. Maybe you’ve been invoking a function dozens of times: it’s time to optimize this so it’ll run even faster! 🏃🏽♀️

The byte code, together with the generated type feedback, is sent to an optimizing compiler. The optimizing compiler takes the byte code and type feedback, and generates highly optimized machine code from these. 🚀

JavaScript is a dynamically typed language, meaning that the types of data can change constantly. It would be extremely slow if the JavaScript engine had to check each time which data type a certain value has.

Instead, the engine uses a technique called inline caching. It caches the code in memory, in the hope that it will return the same value with the same behavior in the future! Say a certain function is invoked a 100 times and has always returned the same value so far. It will assume that it will also return this value the 101st time you invoke it.

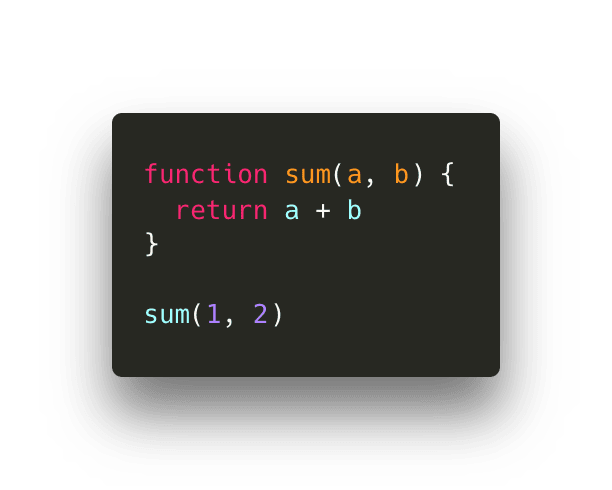

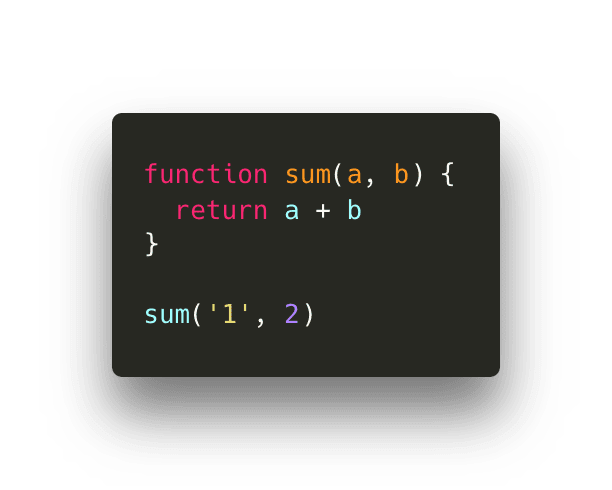

Let’s say that we have the following function sum, that’s (so far) always been called with numerical values as arguments each time:

This returns the number 3! The next time we invoke it, it will assume that we’re invoking it again with two numerical values.

If that’s true, no dynamic lookup is required, and it can just use the result stored in the specific memory slot it already had a reference to. Else, if the assumption was incorrect, it will de-optimize the code and revert back to the original byte code instead of the optimized machine code.

For example, the next time we invoke it, we pass a string instead of a number. Since JavaScript is dynamically typed, we can do this without any errors!

This means that the number 2 will get coerced into a string, and the function will return the string "12" instead. It goes back to executing the interpreted bytecode and updates the type feedback.

I hope this post was useful to you! 😊 Of course, there are many parts to the engine that I haven’t covered in this post (JS heap, call stack, etc.) which I might cover later! I definitely encourage you to start to doing some research yourself if you’re interested in the internals of JavaScript, V8 is open source and has some great documentation on how it works under the hood! 🤖

V8 Docs || V8 Github || Chrome University 2018: Life Of A Script

原文链接:https://dev.to/lydiahallie/javascript-visualized-the-javascript-engine-4cdf