9. Consistency and Consensus

Is it better to be alive and wrong or right and dead?

— Jay Kreps, A Few Notes on Kafka and Jepsen (2013)

Lots of things can go wrong in distributed systems, as discussed in Chapter 8. The simplest way of handling such faults is to simply let the entire service fail, and show the user an error message. If that solution is unacceptable, we need to find ways of tolerating faults—that is, of keeping the service functioning correctly, even if some internal component is faulty.

In this chapter, we will talk about some examples of algorithms and protocols for building fault-tolerant distributed systems. We will assume that all the problems from Chapter 8 can occur: packets can be lost, reordered, duplicated, or arbitrarily delayed in the network; clocks are approximate at best; and nodes can pause (e.g., due to garbage collection) or crash at any time.

The best way of building fault-tolerant systems is to find some general-purpose abstractions with useful guarantees, implement them once, and then let applications rely on those guarantees. This is the same approach as we used with transactions in Chapter 7: by using a transaction, the application can pretend that there are no crashes (atomicity), that nobody else is concurrently accessing the database (isola‐ tion), and that storage devices are perfectly reliable (durability). Even though crashes, race conditions, and disk failures do occur, the transaction abstraction hides those problems so that the application doesn’t need to worry about them.

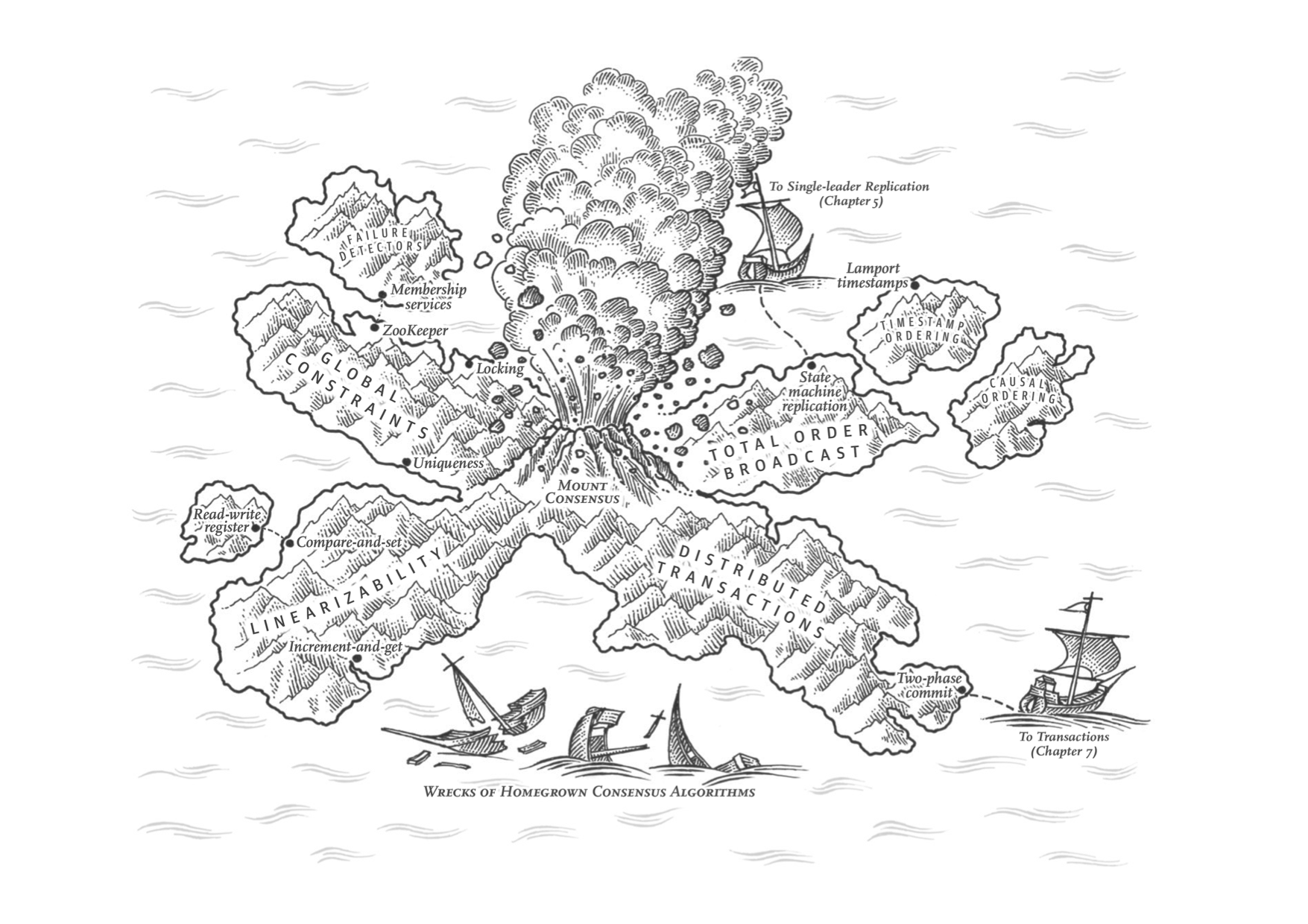

We will now continue along the same lines, and seek abstractions that can allow an application to ignore some of the problems with distributed systems. For example, one of the most important abstractions for distributed systems is consensus: that is, getting all of the nodes to agree on something. As we shall see in this chapter, reliably reaching consensus in spite of network faults and process failures is a surprisingly tricky problem.

Once you have an implementation of consensus, applications can use it for various purposes. For example, say you have a database with single-leader replication. If the leader dies and you need to fail over to another node, the remaining database nodes can use consensus to elect a new leader. As discussed in “Handling Node Outages” on page 156, it’s important that there is only one leader, and that all nodes agree who the leader is. If two nodes both believe that they are the leader, that situation is called split brain, and it often leads to data loss. Correct implementations of consensus help avoid such problems.

Later in this chapter, in “Distributed Transactions and Consensus”, we will look into algorithms to solve consensus and related problems. But first we first need to explore the range of guarantees and abstractions that can be provided in a distributed system.

We need to understand the scope of what can and cannot be done: in some situa‐ tions, it’s possible for the system to tolerate faults and continue working; in other sit‐ uations, that is not possible. The limits of what is and isn’t possible have been explored in depth, both in theoretical proofs and in practical implementations. We will get an overview of those fundamental limits in this chapter.

Researchers in the field of distributed systems have been studying these topics for decades, so there is a lot of material—we’ll only be able to scratch the surface. In this book we don’t have space to go into details of the formal models and proofs, so we will stick with informal intuitions. The literature references offer plenty of additional depth if you’re interested.

……

Summary

In this chapter we examined the topics of consistency and consensus from several different angles. We looked in depth at linearizability, a popular consistency model: its goal is to make replicated data appear as though there were only a single copy, and to make all operations act on it atomically. Although linearizability is appealing because it is easy to understand—it makes a database behave like a variable in a single-threaded program — it has the downside of being slow, especially in environments with large network delays.

We also explored causality, which imposes an ordering on events in a system (what happened before what, based on cause and effect). Unlike linearizability, which puts all operations in a single, totally ordered timeline, causality provides us with a weaker consistency model: some things can be concurrent, so the version history is like a timeline with branching and merging. Causal consistency does not have the coordi‐ nation overhead of linearizability and is much less sensitive to network problems.

However, even if we capture the causal ordering (for example using Lamport timestamps), we saw that some things cannot be implemented this way: in “Timestamp ordering is not sufficient” on page 347 we considered the example of ensuring that a username is unique and rejecting concurrent registrations for the same username. If one node is going to accept a registration, it needs to somehow know that another node isn’t concurrently in the process of registering the same name. This problem led us toward consensus.

We saw that achieving consensus means deciding something in such a way that all nodes agree on what was decided, and such that the decision is irrevocable. With some digging, it turns out that a wide range of problems are actually reducible to consensus and are equivalent to each other (in the sense that if you have a solution for one of them, you can easily transform it into a solution for one of the others). Such equivalent problems include:

Linearizable compare-and-set registers

The register needs to atomically decide whether to set its value, based on whether its current value equals the parameter given in the operation.

Atomic transaction commit

A database must decide whether to commit or abort a distributed transaction.

Total order broadcast

The messaging system must decide on the order in which to deliver messages.

Locks and leases

When several clients are racing to grab a lock or lease, the lock decides which one successfully acquired it.

Membership/coordination service

Given a failure detector (e.g., timeouts), the system must decide which nodes are alive, and which should be considered dead because their sessions timed out.

Uniqueness constraint

When several transactions concurrently try to create conflicting records with the same key, the constraint must decide which one to allow and which should fail with a constraint violation.

All of these are straightforward if you only have a single node, or if you are willing to assign the decision-making capability to a single node. This is what happens in a single-leader database: all the power to make decisions is vested in the leader, which is why such databases are able to provide linearizable operations, uniqueness con‐ straints, a totally ordered replication log, and more.

However, if that single leader fails, or if a network interruption makes the leader unreachable, such a system becomes unable to make any progress. There are three ways of handling that situation:

Wait for the leader to recover, and accept that the system will be blocked in the meantime. Many XA/JTA transaction coordinators choose this option. This approach does not fully solve consensus because it does not satisfy the termina‐ tion property: if the leader does not recover, the system can be blocked forever.

Manually fail over by getting humans to choose a new leader node and reconfig‐ ure the system to use it. Many relational databases take this approach. It is a kind of consensus by “act of God”—the human operator, outside of the computer sys‐ tem, makes the decision. The speed of failover is limited by the speed at which humans can act, which is generally slower than computers.

Use an algorithm to automatically choose a new leader. This approach requires a consensus algorithm, and it is advisable to use a proven algorithm that correctly handles adverse network conditions [107].

Although a single-leader database can provide linearizability without executing a consensus algorithm on every write, it still requires consensus to maintain its leader‐ ship and for leadership changes. Thus, in some sense, having a leader only “kicks the can down the road”: consensus is still required, only in a different place, and less fre‐ quently. The good news is that fault-tolerant algorithms and systems for consensus exist, and we briefly discussed them in this chapter.

Tools like ZooKeeper play an important role in providing an “outsourced” consen‐ sus, failure detection, and membership service that applications can use. It’s not easy to use, but it is much better than trying to develop your own algorithms that can withstand all the problems discussed in Chapter 8. If you find yourself wanting to do one of those things that is reducible to consensus, and you want it to be fault-tolerant, then it is advisable to use something like ZooKeeper.

Nevertheless, not every system necessarily requires consensus: for example, leaderless and multi-leader replication systems typically do not use global consensus. The con‐ flicts that occur in these systems (see “Handling Write Conflicts”) are a consequence of not having consensus across different leaders, but maybe that’s okay: maybe we simply need to cope without linearizability and learn to work better with data that has branching and merging version histories.

This chapter referenced a large body of research on the theory of distributed systems. Although the theoretical papers and proofs are not always easy to understand, and sometimes make unrealistic assumptions, they are incredibly valuable for informing practical work in this field: they help us reason about what can and cannot be done, and help us find the counterintuitive ways in which distributed systems are often flawed. If you have the time, the references are well worth exploring.

This brings us to the end of Part II of this book, in which we covered replication (Chapter 5), partitioning (Chapter 6), transactions (Chapter 7), distributed system failure models (Chapter 8), and finally consistency and consensus (Chapter 9). Now that we have laid a firm foundation of theory, in Part III we will turn once again to more practical systems, and discuss how to build powerful applications from heterogeneous building blocks.

References

Peter Bailis and Ali Ghodsi: “Eventual Consistency Today: Limitations, Extensions, and Beyond,” ACM Queue, volume 11, number 3, pages 55-63, March 2013. doi:10.1145/2460276.2462076

Prince Mahajan, Lorenzo Alvisi, and Mike Dahlin: “Consistency, Availability, and Convergence,” University of Texas at Austin, Department of Computer Science, Tech Report UTCS TR-11-22, May 2011.

Alex Scotti: “Adventures in Building Your Own Database,” at All Your Base, November 2015.

Peter Bailis, Aaron Davidson, Alan Fekete, et al.: “Highly Available Transactions: Virtues and Limitations,” at 40th International Conference on Very Large Data Bases (VLDB), September 2014. Extended version published as pre-print arXiv:1302.0309 [cs.DB].

Paolo Viotti and Marko Vukolić: “Consistency in Non-Transactional Distributed Storage Systems,” arXiv:1512.00168, 12 April 2016.

Maurice P. Herlihy and Jeannette M. Wing: “Linearizability: A Correctness Condition for Concurrent Objects,” ACM Transactions on Programming Languages and Systems (TOPLAS), volume 12, number 3, pages 463–492, July 1990. doi:10.1145/78969.78972

Leslie Lamport: “On interprocess communication,” Distributed Computing, volume 1, number 2, pages 77–101, June 1986. doi:10.1007/BF01786228

David K. Gifford: “Information Storage in a Decentralized Computer System,” Xerox Palo Alto Research Centers, CSL-81-8, June 1981.

Martin Kleppmann: “Please Stop Calling Databases CP or AP,” martin.kleppmann.com, May 11, 2015.

Kyle Kingsbury: “Call Me Maybe: MongoDB Stale Reads,” aphyr.com, April 20, 2015.

Kyle Kingsbury: “Computational Techniques in Knossos,” aphyr.com, May 17, 2014.

Peter Bailis: “Linearizability Versus Serializability,” bailis.org, September 24, 2014.

Philip A. Bernstein, Vassos Hadzilacos, and Nathan Goodman: Concurrency Control and Recovery in Database Systems. Addison-Wesley, 1987. ISBN: 978-0-201-10715-9, available online at research.microsoft.com.

Mike Burrows: “The Chubby Lock Service for Loosely-Coupled Distributed Systems,” at 7th USENIX Symposium on Operating System Design and Implementation (OSDI), November 2006.

Flavio P. Junqueira and Benjamin Reed: ZooKeeper: Distributed Process Coordination. O’Reilly Media, 2013. ISBN: 978-1-449-36130-3

“etcd 2.0.12 Documentation,” CoreOS, Inc., 2015.

“Apache Curator,” Apache Software Foundation, curator.apache.org, 2015.

Morali Vallath: Oracle 10g RAC Grid, Services & Clustering. Elsevier Digital Press, 2006. ISBN: 978-1-555-58321-7

Peter Bailis, Alan Fekete, Michael J Franklin, et al.: “Coordination-Avoiding Database Systems,” Proceedings of the VLDB Endowment, volume 8, number 3, pages 185–196, November 2014.

Kyle Kingsbury: “Call Me Maybe: etcd and Consul,” aphyr.com, June 9, 2014.

Flavio P. Junqueira, Benjamin C. Reed, and Marco Serafini: “Zab: High-Performance Broadcast for Primary-Backup Systems,” at 41st IEEE International Conference on Dependable Systems and Networks (DSN), June 2011. doi:10.1109/DSN.2011.5958223

Diego Ongaro and John K. Ousterhout: “In Search of an Understandable Consensus Algorithm (Extended Version),” at USENIX Annual Technical Conference (ATC), June 2014.

Hagit Attiya, Amotz Bar-Noy, and Danny Dolev: “Sharing Memory Robustly in Message-Passing Systems,” Journal of the ACM, volume 42, number 1, pages 124–142, January 1995. doi:10.1145/200836.200869

Nancy Lynch and Alex Shvartsman: “Robust Emulation of Shared Memory Using Dynamic Quorum-Acknowledged Broadcasts,” at 27th Annual International Symposium on Fault-Tolerant Computing (FTCS), June 1997. doi:10.1109/FTCS.1997.614100

Christian Cachin, Rachid Guerraoui, and Luís Rodrigues: Introduction to Reliable and Secure Distributed Programming, 2nd edition. Springer, 2011. ISBN: 978-3-642-15259-7, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-15260-3

Sam Elliott, Mark Allen, and Martin Kleppmann: personal communication, thread on twitter.com, October 15, 2015.

Niklas Ekström, Mikhail Panchenko, and Jonathan Ellis: “Possible Issue with Read Repair?,” email thread on cassandra-dev mailing list, October 2012.

Maurice P. Herlihy: “Wait-Free Synchronization,” ACM Transactions on Programming Languages and Systems (TOPLAS), volume 13, number 1, pages 124–149, January 1991. doi:10.1145/114005.102808

Armando Fox and Eric A. Brewer: “Harvest, Yield, and Scalable Tolerant Systems,” at 7th Workshop on Hot Topics in Operating Systems (HotOS), March 1999. doi:10.1109/HOTOS.1999.798396

Seth Gilbert and Nancy Lynch: “Brewer’s Conjecture and the Feasibility of Consistent, Available, Partition-Tolerant Web Services,” ACM SIGACT News, volume 33, number 2, pages 51–59, June 2002. doi:10.1145/564585.564601

Seth Gilbert and Nancy Lynch: “Perspectives on the CAP Theorem,” IEEE Computer Magazine, volume 45, number 2, pages 30–36, February 2012. doi:10.1109/MC.2011.389

Eric A. Brewer: “CAP Twelve Years Later: How the ‘Rules’ Have Changed,” IEEE Computer Magazine, volume 45, number 2, pages 23–29, February 2012. doi:10.1109/MC.2012.37

Susan B. Davidson, Hector Garcia-Molina, and Dale Skeen: “Consistency in Partitioned Networks,” ACM Computing Surveys, volume 17, number 3, pages 341–370, September 1985. doi:10.1145/5505.5508

Paul R. Johnson and Robert H. Thomas: “RFC 677: The Maintenance of Duplicate Databases,” Network Working Group, January 27, 1975.

Bruce G. Lindsay, Patricia Griffiths Selinger, C. Galtieri, et al.: “Notes on Distributed Databases,” IBM Research, Research Report RJ2571(33471), July 1979.

Michael J. Fischer and Alan Michael: “Sacrificing Serializability to Attain High Availability of Data in an Unreliable Network,” at 1st ACM Symposium on Principles of Database Systems (PODS), March 1982. doi:10.1145/588111.588124

Eric A. Brewer: “NoSQL: Past, Present, Future,” at QCon San Francisco, November 2012.

Henry Robinson: “CAP Confusion: Problems with ‘Partition Tolerance,’” blog.cloudera.com, April 26, 2010.

Adrian Cockcroft: “Migrating to Microservices,” at QCon London, March 2014.

Martin Kleppmann: “A Critique of the CAP Theorem,” arXiv:1509.05393, September 17, 2015.

Nancy A. Lynch: “A Hundred Impossibility Proofs for Distributed Computing,” at 8th ACM Symposium on Principles of Distributed Computing (PODC), August 1989. doi:10.1145/72981.72982

Hagit Attiya, Faith Ellen, and Adam Morrison: “Limitations of Highly-Available Eventually-Consistent Data Stores](http://www.cs.technion.ac.il/people/mad/online-publications/podc2015-replds.pdf),” at ACM Symposium on Principles of Distributed Computing (PODC), July 2015. doi:10.1145/2767386.2767419

Peter Sewell, Susmit Sarkar, Scott Owens, et al.: “x86-TSO: A Rigorous and Usable Programmer’s Model for x86 Multiprocessors,” Communications of the ACM, volume 53, number 7, pages 89–97, July 2010. doi:10.1145/1785414.1785443

Martin Thompson: “Memory Barriers/Fences,” mechanical-sympathy.blogspot.co.uk, July 24, 2011.

Ulrich Drepper: “What Every Programmer Should Know About Memory,” akkadia.org, November 21, 2007.

Daniel J. Abadi: “Consistency Tradeoffs in Modern Distributed Database System Design,” IEEE Computer Magazine, volume 45, number 2, pages 37–42, February 2012. doi:10.1109/MC.2012.33

Hagit Attiya and Jennifer L. Welch: “Sequential Consistency Versus Linearizability,” ACM Transactions on Computer Systems (TOCS), volume 12, number 2, pages 91–122, May 1994. doi:10.1145/176575.176576

Mustaque Ahamad, Gil Neiger, James E. Burns, et al.: “Causal Memory: Definitions, Implementation, and Programming,” Distributed Computing, volume 9, number 1, pages 37–49, March 1995. doi:10.1007/BF01784241

Wyatt Lloyd, Michael J. Freedman, Michael Kaminsky, and David G. Andersen: “Stronger Semantics for Low-Latency Geo-Replicated Storage,” at 10th USENIX Symposium on Networked Systems Design and Implementation (NSDI), April 2013.

Marek Zawirski, Annette Bieniusa, Valter Balegas, et al.: “SwiftCloud: Fault-Tolerant Geo-Replication Integrated All the Way to the Client Machine,” INRIA Research Report 8347, August 2013.

Peter Bailis, Ali Ghodsi, Joseph M Hellerstein, and Ion Stoica: “Bolt-on Causal Consistency,” at ACM International Conference on Management of Data (SIGMOD), June 2013.

Philippe Ajoux, Nathan Bronson, Sanjeev Kumar, et al.: “Challenges to Adopting Stronger Consistency at Scale,” at 15th USENIX Workshop on Hot Topics in Operating Systems (HotOS), May 2015.

Peter Bailis: “Causality Is Expensive (and What to Do About It),” bailis.org, February 5, 2014.

Ricardo Gonçalves, Paulo Sérgio Almeida, Carlos Baquero, and Victor Fonte: “Concise Server-Wide Causality Management for Eventually Consistent Data Stores,” at 15th IFIP International Conference on Distributed Applications and Interoperable Systems (DAIS), June 2015. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-19129-4_6

Rob Conery: “A Better ID Generator for PostgreSQL,” rob.conery.io, May 29, 2014.

Leslie Lamport: “Time, Clocks, and the Ordering of Events in a Distributed System,” Communications of the ACM, volume 21, number 7, pages 558–565, July 1978. doi:10.1145/359545.359563

Xavier Défago, André Schiper, and Péter Urbán: “Total Order Broadcast and Multicast Algorithms: Taxonomy and Survey,” ACM Computing Surveys, volume 36, number 4, pages 372–421, December 2004. doi:10.1145/1041680.1041682

Hagit Attiya and Jennifer Welch: Distributed Computing: Fundamentals, Simulations and Advanced Topics, 2nd edition. John Wiley & Sons, 2004. ISBN: 978-0-471-45324-6, doi:10.1002/0471478210

Mahesh Balakrishnan, Dahlia Malkhi, Vijayan Prabhakaran, et al.: “CORFU: A Shared Log Design for Flash Clusters,” at 9th USENIX Symposium on Networked Systems Design and Implementation (NSDI), April 2012.

Fred B. Schneider: “Implementing Fault-Tolerant Services Using the State Machine Approach: A Tutorial,” ACM Computing Surveys, volume 22, number 4, pages 299–319, December 1990.

Alexander Thomson, Thaddeus Diamond, Shu-Chun Weng, et al.: “Calvin: Fast Distributed Transactions for Partitioned Database Systems,” at ACM International Conference on Management of Data (SIGMOD), May 2012.

Mahesh Balakrishnan, Dahlia Malkhi, Ted Wobber, et al.: “Tango: Distributed Data Structures over a Shared Log,” at 24th ACM Symposium on Operating Systems Principles (SOSP), November 2013. doi:10.1145/2517349.2522732

Robbert van Renesse and Fred B. Schneider: “Chain Replication for Supporting High Throughput and Availability,” at 6th USENIX Symposium on Operating System Design and Implementation (OSDI), December 2004.

Leslie Lamport: “How to Make a Multiprocessor Computer That Correctly Executes Multiprocess Programs,” IEEE Transactions on Computers, volume 28, number 9, pages 690–691, September 1979. doi:10.1109/TC.1979.1675439

Enis Söztutar, Devaraj Das, and Carter Shanklin: “Apache HBase High Availability at the Next Level,” hortonworks.com, January 22, 2015.

Brian F Cooper, Raghu Ramakrishnan, Utkarsh Srivastava, et al.: “PNUTS: Yahoo!’s Hosted Data Serving Platform,” at 34th International Conference on Very Large Data Bases (VLDB), August 2008. doi:10.14778/1454159.1454167

Tushar Deepak Chandra and Sam Toueg: “Unreliable Failure Detectors for Reliable Distributed Systems,” Journal of the ACM, volume 43, number 2, pages 225–267, March 1996. doi:10.1145/226643.226647

Michael J. Fischer, Nancy Lynch, and Michael S. Paterson: “Impossibility of Distributed Consensus with One Faulty Process,” Journal of the ACM, volume 32, number 2, pages 374–382, April 1985. doi:10.1145/3149.214121

Michael Ben-Or: “Another Advantage of Free Choice: Completely Asynchronous Agreement Protocols,” at 2nd ACM Symposium on Principles of Distributed Computing (PODC), August 1983. doi:10.1145/800221.806707

Jim N. Gray and Leslie Lamport: “Consensus on Transaction Commit,” ACM Transactions on Database Systems (TODS), volume 31, number 1, pages 133–160, March 2006. doi:10.1145/1132863.1132867

Rachid Guerraoui: “Revisiting the Relationship Between Non-Blocking Atomic Commitment and Consensus,” at 9th International Workshop on Distributed Algorithms (WDAG), September 1995. doi:10.1007/BFb0022140

Thanumalayan Sankaranarayana Pillai, Vijay Chidambaram, Ramnatthan Alagappan, et al.: “All File Systems Are Not Created Equal: On the Complexity of Crafting Crash-Consistent Applications,” at 11th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI), October 2014.

Jim Gray: “The Transaction Concept: Virtues and Limitations,” at 7th International Conference on Very Large Data Bases (VLDB), September 1981.

Hector Garcia-Molina and Kenneth Salem: “Sagas,” at ACM International Conference on Management of Data (SIGMOD), May 1987. doi:10.1145/38713.38742

C. Mohan, Bruce G. Lindsay, and Ron Obermarck: “Transaction Management in the R* Distributed Database Management System,” ACM Transactions on Database Systems, volume 11, number 4, pages 378–396, December 1986. doi:10.1145/7239.7266

“Distributed Transaction Processing: The XA Specification,” X/Open Company Ltd., Technical Standard XO/CAE/91/300, December 1991. ISBN: 978-1-872-63024-3

Mike Spille: “XA Exposed, Part II,” jroller.com, April 3, 2004.

Ivan Silva Neto and Francisco Reverbel: “Lessons Learned from Implementing WS-Coordination and WS-AtomicTransaction,” at 7th IEEE/ACIS International Conference on Computer and Information Science (ICIS), May 2008. doi:10.1109/ICIS.2008.75

James E. Johnson, David E. Langworthy, Leslie Lamport, and Friedrich H. Vogt: “Formal Specification of a Web Services Protocol,” at 1st International Workshop on Web Services and Formal Methods (WS-FM), February 2004. doi:10.1016/j.entcs.2004.02.022

Dale Skeen: “Nonblocking Commit Protocols,” at ACM International Conference on Management of Data (SIGMOD), April 1981. doi:10.1145/582318.582339

Gregor Hohpe: “Your Coffee Shop Doesn’t Use Two-Phase Commit,” IEEE Software, volume 22, number 2, pages 64–66, March 2005. doi:10.1109/MS.2005.52

Pat Helland: “Life Beyond Distributed Transactions: An Apostate’s Opinion,” at 3rd Biennial Conference on Innovative Data Systems Research (CIDR), January 2007.

Jonathan Oliver: “My Beef with MSDTC and Two-Phase Commits,” blog.jonathanoliver.com, April 4, 2011.

Oren Eini (Ahende Rahien): “The Fallacy of Distributed Transactions,” ayende.com, July 17, 2014.

Clemens Vasters: “Transactions in Windows Azure (with Service Bus) – An Email Discussion,” vasters.com, July 30, 2012.

“Understanding Transactionality in Azure,” NServiceBus Documentation, Particular Software, 2015.

Randy Wigginton, Ryan Lowe, Marcos Albe, and Fernando Ipar: “Distributed Transactions in MySQL,” at MySQL Conference and Expo, April 2013.

Mike Spille: “XA Exposed, Part I,” jroller.com, April 3, 2004.

Ajmer Dhariwal: “Orphaned MSDTC Transactions (-2 spids),” eraofdata.com, December 12, 2008.

Paul Randal: “Real World Story of DBCC PAGE Saving the Day,” sqlskills.com, June 19, 2013.

“in-doubt xact resolution Server Configuration Option,” SQL Server 2016 documentation, Microsoft, Inc., 2016.

Cynthia Dwork, Nancy Lynch, and Larry Stockmeyer: “Consensus in the Presence of Partial Synchrony,” Journal of the ACM, volume 35, number 2, pages 288–323, April 1988. doi:10.1145/42282.42283

Miguel Castro and Barbara H. Liskov: “Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance and Proactive Recovery,” ACM Transactions on Computer Systems, volume 20, number 4, pages 396–461, November 2002. doi:10.1145/571637.571640

Brian M. Oki and Barbara H. Liskov: “Viewstamped Replication: A New Primary Copy Method to Support Highly-Available Distributed Systems,” at 7th ACM Symposium on Principles of Distributed Computing (PODC), August 1988. doi:10.1145/62546.62549

Barbara H. Liskov and James Cowling: “Viewstamped Replication Revisited,” Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Tech Report MIT-CSAIL-TR-2012-021, July 2012.

Leslie Lamport: “The Part-Time Parliament,” ACM Transactions on Computer Systems, volume 16, number 2, pages 133–169, May 1998. doi:10.1145/279227.279229

Leslie Lamport: “Paxos Made Simple,” ACM SIGACT News, volume 32, number 4, pages 51–58, December 2001.

Tushar Deepak Chandra, Robert Griesemer, and Joshua Redstone: “Paxos Made Live – An Engineering Perspective,” at 26th ACM Symposium on Principles of Distributed Computing (PODC), June 2007.

Robbert van Renesse: “Paxos Made Moderately Complex,” cs.cornell.edu, March 2011.

Diego Ongaro: “Consensus: Bridging Theory and Practice,” PhD Thesis, Stanford University, August 2014.

Heidi Howard, Malte Schwarzkopf, Anil Madhavapeddy, and Jon Crowcroft: “Raft Refloated: Do We Have Consensus?,” ACM SIGOPS Operating Systems Review, volume 49, number 1, pages 12–21, January 2015. doi:10.1145/2723872.2723876

André Medeiros: “ZooKeeper’s Atomic Broadcast Protocol: Theory and Practice,” Aalto University School of Science, March 20, 2012.

Robbert van Renesse, Nicolas Schiper, and Fred B. Schneider: “Vive La Différence: Paxos vs. Viewstamped Replication vs. Zab,” IEEE Transactions on Dependable and Secure Computing, volume 12, number 4, pages 472–484, September 2014. doi:10.1109/TDSC.2014.2355848

Will Portnoy: “Lessons Learned from Implementing Paxos,” blog.willportnoy.com, June 14, 2012.

Heidi Howard, Dahlia Malkhi, and Alexander Spiegelman: “Flexible Paxos: Quorum Intersection Revisited,” arXiv:1608.06696, August 24, 2016.

Heidi Howard and Jon Crowcroft: “Coracle: Evaluating Consensus at the Internet Edge,” at Annual Conference of the ACM Special Interest Group on Data Communication (SIGCOMM), August 2015. doi:10.1145/2829988.2790010

Kyle Kingsbury: “Call Me Maybe: Elasticsearch 1.5.0,” aphyr.com, April 27, 2015.

Ivan Kelly: “BookKeeper Tutorial,” github.com, October 2014.

Camille Fournier: “Consensus Systems for the Skeptical Architect,” at Craft Conference, Budapest, Hungary, April 2015.

Kenneth P. Birman: “A History of the Virtual Synchrony Replication Model,” in Replication: Theory and Practice, Springer LNCS volume 5959, chapter 6, pages 91–120, 2010. ISBN: 978-3-642-11293-5, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-11294-2_6