7. Transactions

Some authors have claimed that general two-phase commit is too expensive to support, because of the performance or availability problems that it brings. We believe it is better to have application programmers deal with performance problems due to overuse of transac‐ tions as bottlenecks arise, rather than always coding around the lack of transactions.

— James Corbett et al., Spanner: Google’s Globally-Distributed Database (2012)

In the harsh reality of data systems, many things can go wrong:

The database software or hardware may fail at any time (including in the middle of a write operation).

The application may crash at any time (including halfway through a series of operations).

Interruptions in the network can unexpectedly cut off the application from the database, or one database node from another.

Several clients may write to the database at the same time, overwriting each other’s changes.

A client may read data that doesn’t make sense because it has only partially been updated.

Race conditions between clients can cause surprising bugs.

In order to be reliable, a system has to deal with these faults and ensure that they don’t cause catastrophic failure of the entire system. However, implementing fault- tolerance mechanisms is a lot of work. It requires a lot of careful thinking about all the things that can go wrong, and a lot of testing to ensure that the solution actually works.

For decades, transactions have been the mechanism of choice for simplifying these issues. A transaction is a way for an application to group several reads and writes together into a logical unit. Conceptually, all the reads and writes in a transaction are executed as one operation: either the entire transaction succeeds (commit) or it fails (abort, rollback). If it fails, the application can safely retry. With transactions, error handling becomes much simpler for an application, because it doesn’t need to worry about partial failure—i.e., the case where some operations succeed and some fail (for whatever reason).

If you have spent years working with transactions, they may seem obvious, but we shouldn’t take them for granted. Transactions are not a law of nature; they were cre‐ ated with a purpose, namely to simplify the programming model for applications accessing a database. By using transactions, the application is free to ignore certain potential error scenarios and concurrency issues, because the database takes care of them instead (we call these safety guarantees).

Not every application needs transactions, and sometimes there are advantages to weakening transactional guarantees or abandoning them entirely (for example, to achieve higher performance or higher availability). Some safety properties can be achieved without transactions.

How do you figure out whether you need transactions? In order to answer that ques‐ tion, we first need to understand exactly what safety guarantees transactions can pro‐ vide, and what costs are associated with them. Although transactions seem straightforward at first glance, there are actually many subtle but important details that come into play.

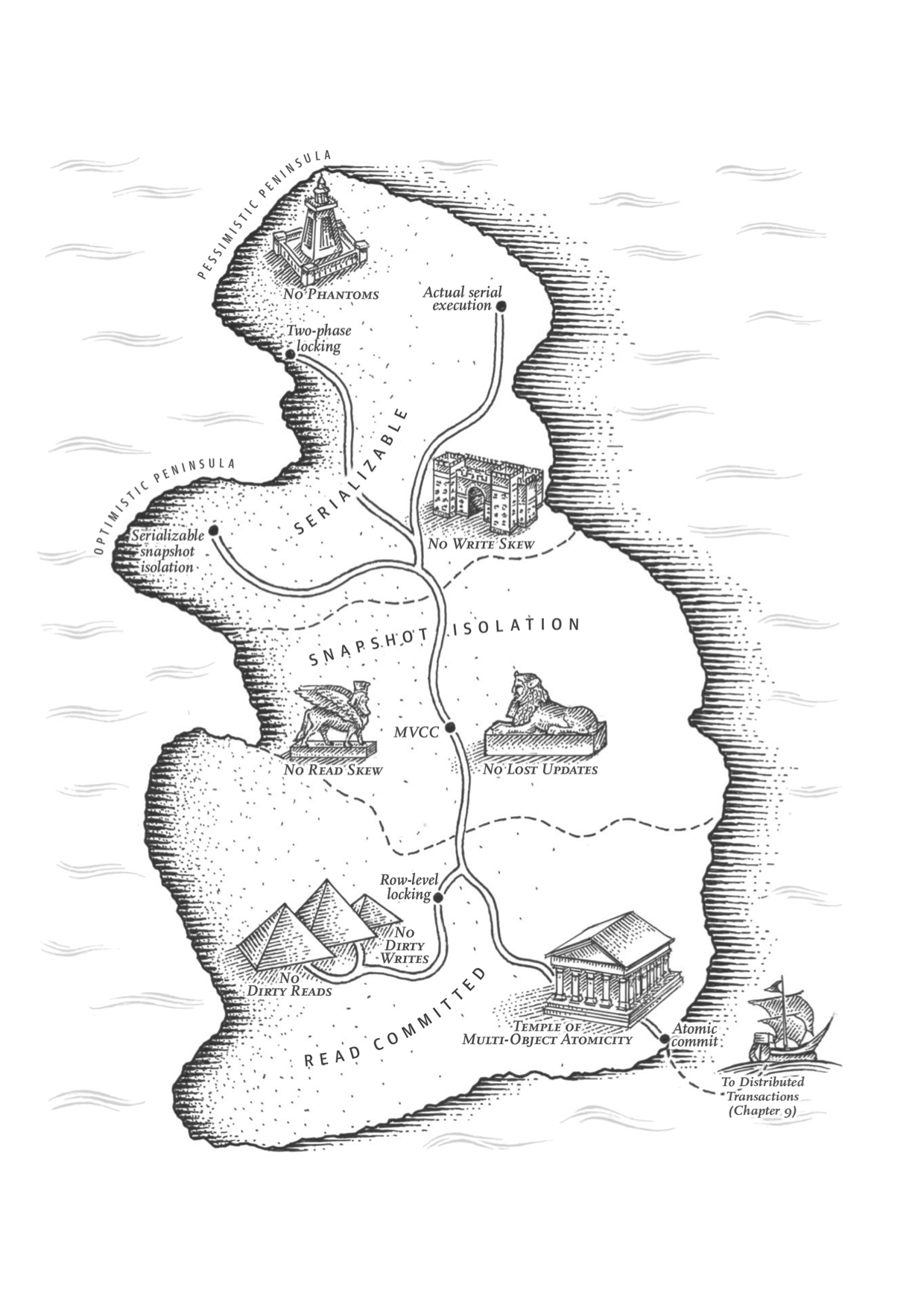

In this chapter, we will examine many examples of things that can go wrong, and explore the algorithms that databases use to guard against those issues. We will go especially deep in the area of concurrency control, discussing various kinds of race conditions that can occur and how databases implement isolation levels such as read committed, snapshot isolation, and serializability.

This chapter applies to both single-node and distributed databases; in Chapter 8 we will focus the discussion on the particular challenges that arise only in distributed systems.

……

Summary

Transactions are an abstraction layer that allows an application to pretend that cer‐ tain concurrency problems and certain kinds of hardware and software faults don’t exist. A large class of errors is reduced down to a simple transaction abort, and the application just needs to try again.

In this chapter we saw many examples of problems that transactions help prevent. Not all applications are susceptible to all those problems: an application with very simple access patterns, such as reading and writing only a single record, can probably manage without transactions. However, for more complex access patterns, transac‐ tions can hugely reduce the number of potential error cases you need to think about.

Without transactions, various error scenarios (processes crashing, network interrup‐ tions, power outages, disk full, unexpected concurrency, etc.) mean that data can become inconsistent in various ways. For example, denormalized data can easily go out of sync with the source data. Without transactions, it becomes very difficult to reason about the effects that complex interacting accesses can have on the database.

In this chapter, we went particularly deep into the topic of concurrency control. We discussed several widely used isolation levels, in particular read committed, snapshot isolation (sometimes called repeatable read), and serializable. We characterized those isolation levels by discussing various examples of race conditions:

Dirty reads

One client reads another client’s writes before they have been committed. The read committed isolation level and stronger levels prevent dirty reads.

Dirty writes

One client overwrites data that another client has written, but not yet committed. Almost all transaction implementations prevent dirty writes.

Read skew (nonrepeatable reads)

A client sees different parts of the database at different points in time. This issue is most commonly prevented with snapshot isolation, which allows a transaction to read from a consistent snapshot at one point in time. It is usually implemented with multi-version concurrency control (MVCC).

Lost updates

Two clients concurrently perform a read-modify-write cycle. One overwrites the other’s write without incorporating its changes, so data is lost. Some implemen‐ tations of snapshot isolation prevent this anomaly automatically, while others require a manual lock (SELECT FOR UPDATE).

Write skew

A transaction reads something, makes a decision based on the value it saw, and writes the decision to the database. However, by the time the write is made, the premise of the decision is no longer true. Only serializable isolation prevents this anomaly.

Phantom reads

A transaction reads objects that match some search condition. Another client makes a write that affects the results of that search. Snapshot isolation prevents straightforward phantom reads, but phantoms in the context of write skew require special treatment, such as index-range locks.

Weak isolation levels protect against some of those anomalies but leave you, the application developer, to handle others manually (e.g., using explicit locking). Only serializable isolation protects against all of these issues. We discussed three different approaches to implementing serializable transactions:

Literally executing transactions in a serial order

If you can make each transaction very fast to execute, and the transaction throughput is low enough to process on a single CPU core, this is a simple and effective option.

Two-phase locking

For decades this has been the standard way of implementing serializability, but many applications avoid using it because of its performance characteristics.

Serializable snapshot isolation (SSI)

A fairly new algorithm that avoids most of the downsides of the previous approaches. It uses an optimistic approach, allowing transactions to proceed without blocking. When a transaction wants to commit, it is checked, and it is aborted if the execution was not serializable.

The examples in this chapter used a relational data model. However, as discussed in “The need for multi-object transactions”, transactions are a valuable database feature, no matter which data model is used.

In this chapter, we explored ideas and algorithms mostly in the context of a database running on a single machine. Transactions in distributed databases open a new set of difficult challenges, which we’ll discuss in the next two chapters.

References

- Donald D. Chamberlin, Morton M. Astrahan, Michael W. Blasgen, et al.: “A History and Evaluation of System R,” Communications of the ACM, volume 24, number 10, pages 632–646, October 1981. doi:10.1145/358769.358784

- Jim N. Gray, Raymond A. Lorie, Gianfranco R. Putzolu, and Irving L. Traiger: “Granularity of Locks and Degrees of Consistency in a Shared Data Base,” in Modelling in Data Base Management Systems: Proceedings of the IFIP Working Conference on Modelling in Data Base Management Systems, edited by G. M. Nijssen, pages 364–394, Elsevier/North Holland Publishing, 1976. Also in Readings in Database Systems, 4th edition, edited by Joseph M. Hellerstein and Michael Stonebraker, MIT Press, 2005. ISBN: 978-0-262-69314-1

- Kapali P. Eswaran, Jim N. Gray, Raymond A. Lorie, and Irving L. Traiger: “The Notions of Consistency and Predicate Locks in a Database System,” Communications of the ACM, volume 19, number 11, pages 624–633, November 1976.

- “ACID Transactions Are Incredibly Helpful,” FoundationDB, LLC, 2013.

- John D. Cook: “ACID Versus BASE for Database Transactions,” johndcook.com, July 6, 2009.

- Gavin Clarke: “NoSQL’s CAP Theorem Busters: We Don’t Drop ACID,” theregister.co.uk, November 22, 2012.

- Theo Härder and Andreas Reuter: “Principles of Transaction-Oriented Database Recovery,” ACM Computing Surveys, volume 15, number 4, pages 287–317, December 1983. doi:10.1145/289.291

- Peter Bailis, Alan Fekete, Ali Ghodsi, et al.: “HAT, not CAP: Towards Highly Available Transactions,” at 14th USENIX Workshop on Hot Topics in Operating Systems (HotOS), May 2013.

- Armando Fox, Steven D. Gribble, Yatin Chawathe, et al.: “Cluster-Based Scalable Network Services,” at 16th ACM Symposium on Operating Systems Principles (SOSP), October 1997.

- Philip A. Bernstein, Vassos Hadzilacos, and Nathan Goodman: Concurrency Control and Recovery in Database Systems. Addison-Wesley, 1987. ISBN: 978-0-201-10715-9, available online at research.microsoft.com.

- Alan Fekete, Dimitrios Liarokapis, Elizabeth O’Neil, et al.: “Making Snapshot Isolation Serializable,” ACM Transactions on Database Systems, volume 30, number 2, pages 492–528, June 2005. doi:10.1145/1071610.1071615

- Mai Zheng, Joseph Tucek, Feng Qin, and Mark Lillibridge: “Understanding the Robustness of SSDs Under Power Fault,” at 11th USENIX Conference on File and Storage Technologies (FAST), February 2013.

- Laurie Denness: “SSDs: A Gift and a Curse,” laur.ie, June 2, 2015.

- Adam Surak: “When Solid State Drives Are Not That Solid,” blog.algolia.com, June 15, 2015.

- Thanumalayan Sankaranarayana Pillai, Vijay Chidambaram, Ramnatthan Alagappan, et al.: “All File Systems Are Not Created Equal: On the Complexity of Crafting Crash-Consistent Applications,” at 11th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI), October 2014.

- Chris Siebenmann: “Unix’s File Durability Problem,” utcc.utoronto.ca, April 14, 2016.

- Lakshmi N. Bairavasundaram, Garth R. Goodson, Bianca Schroeder, et al.: “An Analysis of Data Corruption in the Storage Stack,” at 6th USENIX Conference on File and Storage Technologies (FAST), February 2008.

- Bianca Schroeder, Raghav Lagisetty, and Arif Merchant: “Flash Reliability in Production: The Expected and the Unexpected,” at 14th USENIX Conference on File and Storage Technologies (FAST), February 2016.

- Don Allison: “SSD Storage – Ignorance of Technology Is No Excuse,” blog.korelogic.com, March 24, 2015.

- Dave Scherer: “Those Are Not Transactions (Cassandra 2.0),” blog.foundationdb.com, September 6, 2013.

- Kyle Kingsbury: “Call Me Maybe: Cassandra,” aphyr.com, September 24, 2013.

- “ACID Support in Aerospike,” Aerospike, Inc., June 2014.

- Martin Kleppmann: “Hermitage: Testing the ‘I’ in ACID,” martin.kleppmann.com, November 25, 2014.

- Tristan D’Agosta: “BTC Stolen from Poloniex,” bitcointalk.org, March 4, 2014.

- bitcointhief2: “How I Stole Roughly 100 BTC from an Exchange and How I Could Have Stolen More!,” reddit.com, February 2, 2014.

- Sudhir Jorwekar, Alan Fekete, Krithi Ramamritham, and S. Sudarshan: “Automating the Detection of Snapshot Isolation Anomalies,” at 33rd International Conference on Very Large Data Bases (VLDB), September 2007.

- Michael Melanson: “Transactions: The Limits of Isolation,” michaelmelanson.net, March 20, 2014.

- Hal Berenson, Philip A. Bernstein, Jim N. Gray, et al.: “A Critique of ANSI SQL Isolation Levels,” at ACM International Conference on Management of Data (SIGMOD), May 1995.

- Atul Adya: “Weak Consistency: A Generalized Theory and Optimistic Implementations for Distributed Transactions,” PhD Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, March 1999.

- Peter Bailis, Aaron Davidson, Alan Fekete, et al.: “Highly Available Transactions: Virtues and Limitations (Extended Version),” at 40th International Conference on Very Large Data Bases (VLDB), September 2014.

- Bruce Momjian: “MVCC Unmasked,” momjian.us, July 2014.

- Annamalai Gurusami: “Repeatable Read Isolation Level in InnoDB – How Consistent Read View Works,” blogs.oracle.com, January 15, 2013.

- Nikita Prokopov: “Unofficial Guide to Datomic Internals,” tonsky.me, May 6, 2014.

- Baron Schwartz: “Immutability, MVCC, and Garbage Collection,” xaprb.com, December 28, 2013.

- J. Chris Anderson, Jan Lehnardt, and Noah Slater: CouchDB: The Definitive Guide. O’Reilly Media, 2010. ISBN: 978-0-596-15589-6

- Rikdeb Mukherjee: “Isolation in DB2 (Repeatable Read, Read Stability, Cursor Stability, Uncommitted Read) with Examples,” mframes.blogspot.co.uk, July 4, 2013.

- Steve Hilker: “Cursor Stability (CS) – IBM DB2 Community,” toadworld.com, March 14, 2013.

- Nate Wiger: “An Atomic Rant,” nateware.com, February 18, 2010.

- Joel Jacobson: “Riak 2.0: Data Types,” blog.joeljacobson.com, March 23, 2014.

- Michael J. Cahill, Uwe Röhm, and Alan Fekete: “Serializable Isolation for Snapshot Databases,” at ACM International Conference on Management of Data (SIGMOD), June 2008. doi:10.1145/1376616.1376690

- Dan R. K. Ports and Kevin Grittner: “Serializable Snapshot Isolation in PostgreSQL,” at 38th International Conference on Very Large Databases (VLDB), August 2012.

- Tony Andrews: “Enforcing Complex Constraints in Oracle,” tonyandrews.blogspot.co.uk, October 15, 2004.

- Douglas B. Terry, Marvin M. Theimer, Karin Petersen, et al.: “Managing Update Conflicts in Bayou, a Weakly Connected Replicated Storage System,” at 15th ACM Symposium on Operating Systems Principles (SOSP), December 1995. doi:10.1145/224056.224070

- Gary Fredericks: “Postgres Serializability Bug,” github.com, September 2015.

- Michael Stonebraker, Samuel Madden, Daniel J. Abadi, et al.: “The End of an Architectural Era (It’s Time for a Complete Rewrite),” at 33rd International Conference on Very Large Data Bases (VLDB), September 2007.

- John Hugg: “H-Store/VoltDB Architecture vs. CEP Systems and Newer Streaming Architectures,” at Data @Scale Boston, November 2014.

- Robert Kallman, Hideaki Kimura, Jonathan Natkins, et al.: “H-Store: A High-Performance, Distributed Main Memory Transaction Processing System,” Proceedings of the VLDB Endowment, volume 1, number 2, pages 1496–1499, August 2008.

- Rich Hickey: “The Architecture of Datomic,” infoq.com, November 2, 2012.

- John Hugg: “Debunking Myths About the VoltDB In-Memory Database,” voltdb.com, May 12, 2014.

- Joseph M. Hellerstein, Michael Stonebraker, and James Hamilton: “Architecture of a Database System,” Foundations and Trends in Databases, volume 1, number 2, pages 141–259, November 2007. doi:10.1561/1900000002

- Michael J. Cahill: “Serializable Isolation for Snapshot Databases,” PhD Thesis, University of Sydney, July 2009.

- D. Z. Badal: “Correctness of Concurrency Control and Implications in Distributed Databases,” at 3rd International IEEE Computer Software and Applications Conference (COMPSAC), November 1979.

- Rakesh Agrawal, Michael J. Carey, and Miron Livny: “Concurrency Control Performance Modeling: Alternatives and Implications,” ACM Transactions on Database Systems (TODS), volume 12, number 4, pages 609–654, December 1987. doi:10.1145/32204.32220

- Dave Rosenthal: “Databases at 14.4MHz,” blog.foundationdb.com, December 10, 2014.