- Intro to Data Structures

- Series

- DataFrame

- From dict of Series or dicts

- From dict of ndarrays / lists

- From structured or record array

- From a list of dicts

- From a dict of tuples

- From a Series

- Alternate Constructors

- Column selection, addition, deletion

- Assigning New Columns in Method Chains

- Indexing / Selection

- Data alignment and arithmetic

- Transposing

- DataFrame interoperability with NumPy functions

- Console display

- DataFrame column attribute access and IPython completion

- Panel

- Deprecate Panel

Intro to Data Structures

We’ll start with a quick, non-comprehensive overview of the fundamental data structures in pandas to get you started. The fundamental behavior about data types, indexing, and axis labeling / alignment apply across all of the objects. To get started, import NumPy and load pandas into your namespace:

In [1]: import numpy as npIn [2]: import pandas as pd

Here is a basic tenet to keep in mind: data alignment is intrinsic. The link between labels and data will not be broken unless done so explicitly by you.

We’ll give a brief intro to the data structures, then consider all of the broad categories of functionality and methods in separate sections.

Series

Series is a one-dimensional labeled array capable of holding any data type (integers, strings, floating point numbers, Python objects, etc.). The axis labels are collectively referred to as the index. The basic method to create a Series is to call:

>>> s = pd.Series(data, index=index)

Here, data can be many different things:

- a Python dict

- an ndarray

- a scalar value (like 5)

The passed index is a list of axis labels. Thus, this separates into a few cases depending on what data is:

From ndarray

If data is an ndarray, index must be the same length as data. If no index is passed, one will be created having values [0, ..., len(data) - 1].

In [3]: s = pd.Series(np.random.randn(5), index=['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e'])In [4]: sOut[4]:a 0.469112b -0.282863c -1.509059d -1.135632e 1.212112dtype: float64In [5]: s.indexOut[5]: Index(['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e'], dtype='object')In [6]: pd.Series(np.random.randn(5))Out[6]:0 -0.1732151 0.1192092 -1.0442363 -0.8618494 -2.104569dtype: float64

::: tip Note pandas supports non-unique index values. If an operation that does not support duplicate index values is attempted, an exception will be raised at that time. The reason for being lazy is nearly all performance-based (there are many instances in computations, like parts of GroupBy, where the index is not used). :::

From dict

Series can be instantiated from dicts:

In [7]: d = {'b': 1, 'a': 0, 'c': 2}In [8]: pd.Series(d)Out[8]:b 1a 0c 2dtype: int64

::: tip Note

When the data is a dict, and an index is not passed, the Series index will be ordered by the dict’s insertion order, if you’re using Python version >= 3.6 and Pandas version >= 0.23.

If you’re using Python < 3.6 or Pandas < 0.23, and an index is not passed, the Series index will be the lexically ordered list of dict keys.

:::

In the example above, if you were on a Python version lower than 3.6 or a Pandas version lower than 0.23, the Series would be ordered by the lexical order of the dict keys (i.e. ['a', 'b', 'c'] rather than ['b', 'a', 'c']).

If an index is passed, the values in data corresponding to the labels in the index will be pulled out.

In [9]: d = {'a': 0., 'b': 1., 'c': 2.}In [10]: pd.Series(d)Out[10]:a 0.0b 1.0c 2.0dtype: float64In [11]: pd.Series(d, index=['b', 'c', 'd', 'a'])Out[11]:b 1.0c 2.0d NaNa 0.0dtype: float64

::: tip Note NaN (not a number) is the standard missing data marker used in pandas. :::

From scalar value

If data is a scalar value, an index must be provided. The value will be repeated to match the length of index.

In [12]: pd.Series(5., index=['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e'])Out[12]:a 5.0b 5.0c 5.0d 5.0e 5.0dtype: float64

Series is ndarray-like

Series acts very similarly to a ndarray, and is a valid argument to most NumPy functions. However, operations such as slicing will also slice the index.

In [13]: s[0]Out[13]: 0.46911229990718628In [14]: s[:3]Out[14]:a 0.469112b -0.282863c -1.509059dtype: float64In [15]: s[s > s.median()]Out[15]:a 0.469112e 1.212112dtype: float64In [16]: s[[4, 3, 1]]Out[16]:e 1.212112d -1.135632b -0.282863dtype: float64In [17]: np.exp(s)Out[17]:a 1.598575b 0.753623c 0.221118d 0.321219e 3.360575dtype: float64

Note We will address array-based indexing like s[[4, 3, 1]] in section.

Like a NumPy array, a pandas Series has a dtype.

In [18]: s.dtypeOut[18]: dtype('float64')

This is often a NumPy dtype. However, pandas and 3rd-party libraries extend NumPy’s type system in a few places, in which case the dtype would be a ExtensionDtype. Some examples within pandas are Categorical Data and Nullable Integer Data Type. See dtypes for more.

If you need the actual array backing a Series, use Series.array.

In [19]: s.arrayOut[19]:<PandasArray>[ 0.46911229990718628, -0.28286334432866328, -1.5090585031735124,-1.1356323710171934, 1.2121120250208506]Length: 5, dtype: float64

Accessing the array can be useful when you need to do some operation without the index (to disable automatic alignment, for example).

Series.array will always be an ExtensionArray. Briefly, an ExtensionArray is a thin wrapper around one or more concrete arrays like a numpy.ndarray. Pandas knows how to take an ExtensionArray and store it in a Series or a column of a DataFrame. See dtypes for more.

While Series is ndarray-like, if you need an actual ndarray, then use Series.to_numpy().

In [20]: s.to_numpy()Out[20]: array([ 0.4691, -0.2829, -1.5091, -1.1356, 1.2121])

Even if the Series is backed by a ExtensionArray, Series.to_numpy() will return a NumPy ndarray.

Series is dict-like

A Series is like a fixed-size dict in that you can get and set values by index label:

In [21]: s['a']Out[21]: 0.46911229990718628In [22]: s['e'] = 12.In [23]: sOut[23]:a 0.469112b -0.282863c -1.509059d -1.135632e 12.000000dtype: float64In [24]: 'e' in sOut[24]: TrueIn [25]: 'f' in sOut[25]: False

If a label is not contained, an exception is raised:

>>> s['f']KeyError: 'f'

Using the get method, a missing label will return None or specified default:

In [26]: s.get('f')In [27]: s.get('f', np.nan)Out[27]: nan

See also the section on attribute access.

Vectorized operations and label alignment with Series

When working with raw NumPy arrays, looping through value-by-value is usually not necessary. The same is true when working with Series in pandas. Series can also be passed into most NumPy methods expecting an ndarray.

In [28]: s + sOut[28]:a 0.938225b -0.565727c -3.018117d -2.271265e 24.000000dtype: float64In [29]: s * 2Out[29]:a 0.938225b -0.565727c -3.018117d -2.271265e 24.000000dtype: float64In [30]: np.exp(s)Out[30]:a 1.598575b 0.753623c 0.221118d 0.321219e 162754.791419dtype: float64

A key difference between Series and ndarray is that operations between Series automatically align the data based on label. Thus, you can write computations without giving consideration to whether the Series involved have the same labels.

In [31]: s[1:] + s[:-1]Out[31]:a NaNb -0.565727c -3.018117d -2.271265e NaNdtype: float64

The result of an operation between unaligned Series will have the union of the indexes involved. If a label is not found in one Series or the other, the result will be marked as missing NaN. Being able to write code without doing any explicit data alignment grants immense freedom and flexibility in interactive data analysis and research. The integrated data alignment features of the pandas data structures set pandas apart from the majority of related tools for working with labeled data.

::: tip Note In general, we chose to make the default result of operations between differently indexed objects yield the union of the indexes in order to avoid loss of information. Having an index label, though the data is missing, is typically important information as part of a computation. You of course have the option of dropping labels with missing data via the dropna function. :::

Name attribute

Series can also have a name attribute:

In [32]: s = pd.Series(np.random.randn(5), name='something')In [33]: sOut[33]:0 -0.4949291 1.0718042 0.7215553 -0.7067714 -1.039575Name: something, dtype: float64In [34]: s.nameOut[34]: 'something'

The Series name will be assigned automatically in many cases, in particular when taking 1D slices of DataFrame as you will see below.

New in version 0.18.0.

You can rename a Series with the pandas.Series.rename() method.

In [35]: s2 = s.rename("different")In [36]: s2.nameOut[36]: 'different'

Note that s and s2 refer to different objects.

DataFrame

DataFrame is a 2-dimensional labeled data structure with columns of potentially different types. You can think of it like a spreadsheet or SQL table, or a dict of Series objects. It is generally the most commonly used pandas object. Like Series, DataFrame accepts many different kinds of input:

- Dict of 1D ndarrays, lists, dicts, or Series

- 2-D numpy.ndarray

- Structured or record ndarray

- A Series

- Another DataFrame

Along with the data, you can optionally pass index (row labels) and columns (column labels) arguments. If you pass an index and / or columns, you are guaranteeing the index and / or columns of the resulting DataFrame. Thus, a dict of Series plus a specific index will discard all data not matching up to the passed index.

If axis labels are not passed, they will be constructed from the input data based on common sense rules.

::: tip Note

When the data is a dict, and columns is not specified, the DataFrame columns will be ordered by the dict’s insertion order, if you are using Python version >= 3.6 and Pandas >= 0.23.

If you are using Python < 3.6 or Pandas < 0.23, and columns is not specified, the DataFrame columns will be the lexically ordered list of dict keys. :::

From dict of Series or dicts

The resulting index will be the union of the indexes of the various Series. If there are any nested dicts, these will first be converted to Series. If no columns are passed, the columns will be the ordered list of dict keys.

In [37]: d = {'one': pd.Series([1., 2., 3.], index=['a', 'b', 'c']),....: 'two': pd.Series([1., 2., 3., 4.], index=['a', 'b', 'c', 'd'])}....:In [38]: df = pd.DataFrame(d)In [39]: dfOut[39]:one twoa 1.0 1.0b 2.0 2.0c 3.0 3.0d NaN 4.0In [40]: pd.DataFrame(d, index=['d', 'b', 'a'])Out[40]:one twod NaN 4.0b 2.0 2.0a 1.0 1.0In [41]: pd.DataFrame(d, index=['d', 'b', 'a'], columns=['two', 'three'])Out[41]:two threed 4.0 NaNb 2.0 NaNa 1.0 NaN

The row and column labels can be accessed respectively by accessing the index and columns attributes:

::: tip Note When a particular set of columns is passed along with a dict of data, the passed columns override the keys in the dict. :::

In [42]: df.indexOut[42]: Index(['a', 'b', 'c', 'd'], dtype='object')In [43]: df.columnsOut[43]: Index(['one', 'two'], dtype='object')

From dict of ndarrays / lists

The ndarrays must all be the same length. If an index is passed, it must clearly also be the same length as the arrays. If no index is passed, the result will be range(n), where n is the array length.

In [44]: d = {'one': [1., 2., 3., 4.],....: 'two': [4., 3., 2., 1.]}....:In [45]: pd.DataFrame(d)Out[45]:one two0 1.0 4.01 2.0 3.02 3.0 2.03 4.0 1.0In [46]: pd.DataFrame(d, index=['a', 'b', 'c', 'd'])Out[46]:one twoa 1.0 4.0b 2.0 3.0c 3.0 2.0d 4.0 1.0

From structured or record array

This case is handled identically to a dict of arrays.

In [47]: data = np.zeros((2, ), dtype=[('A', 'i4'), ('B', 'f4'), ('C', 'a10')])In [48]: data[:] = [(1, 2., 'Hello'), (2, 3., "World")]In [49]: pd.DataFrame(data)Out[49]:A B C0 1 2.0 b'Hello'1 2 3.0 b'World'In [50]: pd.DataFrame(data, index=['first', 'second'])Out[50]:A B Cfirst 1 2.0 b'Hello'second 2 3.0 b'World'In [51]: pd.DataFrame(data, columns=['C', 'A', 'B'])Out[51]:C A B0 b'Hello' 1 2.01 b'World' 2 3.0

::: tip Note DataFrame is not intended to work exactly like a 2-dimensional NumPy ndarray. :::

From a list of dicts

In [52]: data2 = [{'a': 1, 'b': 2}, {'a': 5, 'b': 10, 'c': 20}]In [53]: pd.DataFrame(data2)Out[53]:a b c0 1 2 NaN1 5 10 20.0In [54]: pd.DataFrame(data2, index=['first', 'second'])Out[54]:a b cfirst 1 2 NaNsecond 5 10 20.0In [55]: pd.DataFrame(data2, columns=['a', 'b'])Out[55]:a b0 1 21 5 10

From a dict of tuples

You can automatically create a MultiIndexed frame by passing a tuples dictionary.

In [56]: pd.DataFrame({('a', 'b'): {('A', 'B'): 1, ('A', 'C'): 2},....: ('a', 'a'): {('A', 'C'): 3, ('A', 'B'): 4},....: ('a', 'c'): {('A', 'B'): 5, ('A', 'C'): 6},....: ('b', 'a'): {('A', 'C'): 7, ('A', 'B'): 8},....: ('b', 'b'): {('A', 'D'): 9, ('A', 'B'): 10}})....:Out[56]:a bb a c a bA B 1.0 4.0 5.0 8.0 10.0C 2.0 3.0 6.0 7.0 NaND NaN NaN NaN NaN 9.0

From a Series

The result will be a DataFrame with the same index as the input Series, and with one column whose name is the original name of the Series (only if no other column name provided).

Missing Data

Much more will be said on this topic in the Missing data section. To construct a DataFrame with missing data, we use np.nan to represent missing values. Alternatively, you may pass a numpy.MaskedArray as the data argument to the DataFrame constructor, and its masked entries will be considered missing.

Alternate Constructors

DataFrame.from_dict

DataFrame.from_dict takes a dict of dicts or a dict of array-like sequences and returns a DataFrame. It operates like the DataFrame constructor except for the orient parameter which is 'columns' by default, but which can be set to 'index' in order to use the dict keys as row labels.

In [57]: pd.DataFrame.from_dict(dict([('A', [1, 2, 3]), ('B', [4, 5, 6])]))Out[57]:A B0 1 41 2 52 3 6

If you pass orient='index', the keys will be the row labels. In this case, you can also pass the desired column names:

In [58]: pd.DataFrame.from_dict(dict([('A', [1, 2, 3]), ('B', [4, 5, 6])]),....: orient='index', columns=['one', 'two', 'three'])....:Out[58]:one two threeA 1 2 3B 4 5 6

DataFrame.from_records

DataFrame.from_records takes a list of tuples or an ndarray with structured dtype. It works analogously to the normal DataFrame constructor, except that the resulting DataFrame index may be a specific field of the structured dtype. For example:

In [59]: dataOut[59]:array([(1, 2., b'Hello'), (2, 3., b'World')],dtype=[('A', '<i4'), ('B', '<f4'), ('C', 'S10')])In [60]: pd.DataFrame.from_records(data, index='C')Out[60]:A BCb'Hello' 1 2.0b'World' 2 3.0

Column selection, addition, deletion

You can treat a DataFrame semantically like a dict of like-indexed Series objects. Getting, setting, and deleting columns works with the same syntax as the analogous dict operations:

In [61]: df['one']Out[61]:a 1.0b 2.0c 3.0d NaNName: one, dtype: float64In [62]: df['three'] = df['one'] * df['two']In [63]: df['flag'] = df['one'] > 2In [64]: dfOut[64]:one two three flaga 1.0 1.0 1.0 Falseb 2.0 2.0 4.0 Falsec 3.0 3.0 9.0 Trued NaN 4.0 NaN False

Columns can be deleted or popped like with a dict:

In [65]: del df['two']In [66]: three = df.pop('three')In [67]: dfOut[67]:one flaga 1.0 Falseb 2.0 Falsec 3.0 Trued NaN False

When inserting a scalar value, it will naturally be propagated to fill the column:

In [68]: df['foo'] = 'bar'In [69]: dfOut[69]:one flag fooa 1.0 False barb 2.0 False barc 3.0 True bard NaN False bar

When inserting a Series that does not have the same index as the DataFrame, it will be conformed to the DataFrame’s index:

In [70]: df['one_trunc'] = df['one'][:2]In [71]: dfOut[71]:one flag foo one_trunca 1.0 False bar 1.0b 2.0 False bar 2.0c 3.0 True bar NaNd NaN False bar NaN

You can insert raw ndarrays but their length must match the length of the DataFrame’s index.

By default, columns get inserted at the end. The insert function is available to insert at a particular location in the columns:

In [72]: df.insert(1, 'bar', df['one'])In [73]: dfOut[73]:one bar flag foo one_trunca 1.0 1.0 False bar 1.0b 2.0 2.0 False bar 2.0c 3.0 3.0 True bar NaNd NaN NaN False bar NaN

Assigning New Columns in Method Chains

Inspired by dplyr’s mutate verb, DataFrame has an assign() method that allows you to easily create new columns that are potentially derived from existing columns.

In [74]: iris = pd.read_csv('data/iris.data')In [75]: iris.head()Out[75]:SepalLength SepalWidth PetalLength PetalWidth Name0 5.1 3.5 1.4 0.2 Iris-setosa1 4.9 3.0 1.4 0.2 Iris-setosa2 4.7 3.2 1.3 0.2 Iris-setosa3 4.6 3.1 1.5 0.2 Iris-setosa4 5.0 3.6 1.4 0.2 Iris-setosaIn [76]: (iris.assign(sepal_ratio=iris['SepalWidth'] / iris['SepalLength'])....: .head())....:Out[76]:SepalLength SepalWidth PetalLength PetalWidth Name sepal_ratio0 5.1 3.5 1.4 0.2 Iris-setosa 0.6862751 4.9 3.0 1.4 0.2 Iris-setosa 0.6122452 4.7 3.2 1.3 0.2 Iris-setosa 0.6808513 4.6 3.1 1.5 0.2 Iris-setosa 0.6739134 5.0 3.6 1.4 0.2 Iris-setosa 0.720000

In the example above, we inserted a precomputed value. We can also pass in a function of one argument to be evaluated on the DataFrame being assigned to.

In [77]: iris.assign(sepal_ratio=lambda x: (x['SepalWidth'] / x['SepalLength'])).head()Out[77]:SepalLength SepalWidth PetalLength PetalWidth Name sepal_ratio0 5.1 3.5 1.4 0.2 Iris-setosa 0.6862751 4.9 3.0 1.4 0.2 Iris-setosa 0.6122452 4.7 3.2 1.3 0.2 Iris-setosa 0.6808513 4.6 3.1 1.5 0.2 Iris-setosa 0.6739134 5.0 3.6 1.4 0.2 Iris-setosa 0.720000

assign always returns a copy of the data, leaving the original DataFrame untouched.

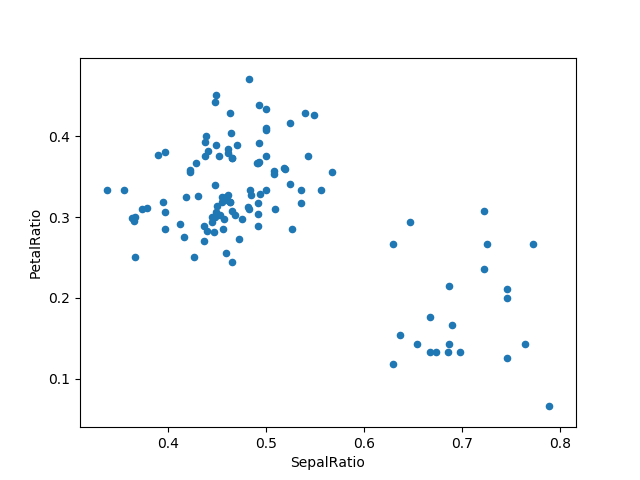

Passing a callable, as opposed to an actual value to be inserted, is useful when you don’t have a reference to the DataFrame at hand. This is common when using assign in a chain of operations. For example, we can limit the DataFrame to just those observations with a Sepal Length greater than 5, calculate the ratio, and plot:

In [78]: (iris.query('SepalLength > 5')....: .assign(SepalRatio=lambda x: x.SepalWidth / x.SepalLength,....: PetalRatio=lambda x: x.PetalWidth / x.PetalLength)....: .plot(kind='scatter', x='SepalRatio', y='PetalRatio'))....:Out[78]: <matplotlib.axes._subplots.AxesSubplot at 0x7f2b527b1a58>

Since a function is passed in, the function is computed on the DataFrame being assigned to. Importantly, this is the DataFrame that’s been filtered to those rows with sepal length greater than 5. The filtering happens first, and then the ratio calculations. This is an example where we didn’t have a reference to the filtered DataFrame available.

The function signature for assign is simply **kwargs. The keys are the column names for the new fields, and the values are either a value to be inserted (for example, a Series or NumPy array), or a function of one argument to be called on the DataFrame. A copy of the original DataFrame is returned, with the new values inserted.

Changed in version 0.23.0.

Starting with Python 3.6 the order of **kwargs is preserved. This allows for dependent assignment, where an expression later in **kwargs can refer to a column created earlier in the same assign().

In [79]: dfa = pd.DataFrame({"A": [1, 2, 3],....: "B": [4, 5, 6]})....:In [80]: dfa.assign(C=lambda x: x['A'] + x['B'],....: D=lambda x: x['A'] + x['C'])....:Out[80]:A B C D0 1 4 5 61 2 5 7 92 3 6 9 12

In the second expression, x['C'] will refer to the newly created column, that’s equal to dfa['A'] + dfa['B'].

To write code compatible with all versions of Python, split the assignment in two.

In [81]: dependent = pd.DataFrame({"A": [1, 1, 1]})In [82]: (dependent.assign(A=lambda x: x['A'] + 1)....: .assign(B=lambda x: x['A'] + 2))....:Out[82]:A B0 2 41 2 42 2 4

::: danger Warning

Dependent assignment maybe subtly change the behavior of your code between Python 3.6 and older versions of Python.

If you wish write code that supports versions of python before and after 3.6, you’ll need to take care when passing assign expressions that

- Updating an existing column

- Referring to the newly updated column in the same

assign

For example, we’ll update column “A” and then refer to it when creating “B”.

>>> dependent = pd.DataFrame({"A": [1, 1, 1]})>>> dependent.assign(A=lambda x: x["A"] + 1, B=lambda x: x["A"] + 2)

For Python 3.5 and earlier the expression creating B refers to the “old” value of A, [1, 1, 1]. The output is then

A B0 2 31 2 32 2 3

For Python 3.6 and later, the expression creating A refers to the “new” value of A, [2, 2, 2], which results in

A B0 2 41 2 42 2 4

:::

Indexing / Selection

The basics of indexing are as follows:

| Operation | Syntax | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Select column | df[col] | Series |

| Select row by label | df.loc[label] | Series |

| Select row by integer location | df.iloc[loc] | Series |

| Slice rows | df[5:10] | DataFrame |

| Select rows by boolean vector | df[bool_vec] | DataFrame |

Row selection, for example, returns a Series whose index is the columns of the DataFrame:

In [83]: df.loc['b']Out[83]:one 2bar 2flag Falsefoo barone_trunc 2Name: b, dtype: objectIn [84]: df.iloc[2]Out[84]:one 3bar 3flag Truefoo barone_trunc NaNName: c, dtype: object

For a more exhaustive treatment of sophisticated label-based indexing and slicing, see the section on indexing. We will address the fundamentals of reindexing / conforming to new sets of labels in the section on reindexing.

Data alignment and arithmetic

Data alignment between DataFrame objects automatically align on both the columns and the index (row labels). Again, the resulting object will have the union of the column and row labels.

In [85]: df = pd.DataFrame(np.random.randn(10, 4), columns=['A', 'B', 'C', 'D'])In [86]: df2 = pd.DataFrame(np.random.randn(7, 3), columns=['A', 'B', 'C'])In [87]: df + df2Out[87]:A B C D0 0.045691 -0.014138 1.380871 NaN1 -0.955398 -1.501007 0.037181 NaN2 -0.662690 1.534833 -0.859691 NaN3 -2.452949 1.237274 -0.133712 NaN4 1.414490 1.951676 -2.320422 NaN5 -0.494922 -1.649727 -1.084601 NaN6 -1.047551 -0.748572 -0.805479 NaN7 NaN NaN NaN NaN8 NaN NaN NaN NaN9 NaN NaN NaN NaN

When doing an operation between DataFrame and Series, the default behavior is to align the Series index on the DataFrame columns, thus broadcasting row-wise. For example:

In [88]: df - df.iloc[0]Out[88]:A B C D0 0.000000 0.000000 0.000000 0.0000001 -1.359261 -0.248717 -0.453372 -1.7546592 0.253128 0.829678 0.010026 -1.9912343 -1.311128 0.054325 -1.724913 -1.6205444 0.573025 1.500742 -0.676070 1.3673315 -1.741248 0.781993 -1.241620 -2.0531366 -1.240774 -0.869551 -0.153282 0.0004307 -0.743894 0.411013 -0.929563 -0.2823868 -1.194921 1.320690 0.238224 -1.4826449 2.293786 1.856228 0.773289 -1.446531

In the special case of working with time series data, and the DataFrame index also contains dates, the broadcasting will be column-wise:

In [89]: index = pd.date_range('1/1/2000', periods=8)In [90]: df = pd.DataFrame(np.random.randn(8, 3), index=index, columns=list('ABC'))In [91]: dfOut[91]:A B C2000-01-01 -1.226825 0.769804 -1.2812472000-01-02 -0.727707 -0.121306 -0.0978832000-01-03 0.695775 0.341734 0.9597262000-01-04 -1.110336 -0.619976 0.1497482000-01-05 -0.732339 0.687738 0.1764442000-01-06 0.403310 -0.154951 0.3016242000-01-07 -2.179861 -1.369849 -0.9542082000-01-08 1.462696 -1.743161 -0.826591In [92]: type(df['A'])Out[92]: pandas.core.series.SeriesIn [93]: df - df['A']Out[93]:2000-01-01 00:00:00 2000-01-02 00:00:00 2000-01-03 00:00:00 2000-01-04 00:00:00 2000-01-05 00:00:00 ... 2000-01-07 00:00:00 2000-01-08 00:00:00 A B C2000-01-01 NaN NaN NaN NaN NaN ... NaN NaN NaN NaN NaN2000-01-02 NaN NaN NaN NaN NaN ... NaN NaN NaN NaN NaN2000-01-03 NaN NaN NaN NaN NaN ... NaN NaN NaN NaN NaN2000-01-04 NaN NaN NaN NaN NaN ... NaN NaN NaN NaN NaN2000-01-05 NaN NaN NaN NaN NaN ... NaN NaN NaN NaN NaN2000-01-06 NaN NaN NaN NaN NaN ... NaN NaN NaN NaN NaN2000-01-07 NaN NaN NaN NaN NaN ... NaN NaN NaN NaN NaN2000-01-08 NaN NaN NaN NaN NaN ... NaN NaN NaN NaN NaN[8 rows x 11 columns]

::: danger Warning

df - df['A']

is now deprecated and will be removed in a future release. The preferred way to replicate this behavior is

df.sub(df['A'], axis=0)

:::

For explicit control over the matching and broadcasting behavior, see the section on flexible binary operations.

Operations with scalars are just as you would expect:

In [94]: df * 5 + 2Out[94]:A B C2000-01-01 -4.134126 5.849018 -4.4062372000-01-02 -1.638535 1.393469 1.5105872000-01-03 5.478873 3.708672 6.7986282000-01-04 -3.551681 -1.099880 2.7487422000-01-05 -1.661697 5.438692 2.8822222000-01-06 4.016548 1.225246 3.5081222000-01-07 -8.899303 -4.849247 -2.7710392000-01-08 9.313480 -6.715805 -2.132955In [95]: 1 / dfOut[95]:A B C2000-01-01 -0.815112 1.299033 -0.7804892000-01-02 -1.374179 -8.243600 -10.2163132000-01-03 1.437247 2.926250 1.0419652000-01-04 -0.900628 -1.612966 6.6778712000-01-05 -1.365487 1.454041 5.6675102000-01-06 2.479485 -6.453662 3.3153812000-01-07 -0.458745 -0.730007 -1.0479902000-01-08 0.683669 -0.573671 -1.209788In [96]: df ** 4Out[96]:A B C2000-01-01 2.265327 0.351172 2.6948332000-01-02 0.280431 0.000217 0.0000922000-01-03 0.234355 0.013638 0.8483762000-01-04 1.519910 0.147740 0.0005032000-01-05 0.287640 0.223714 0.0009692000-01-06 0.026458 0.000576 0.0082772000-01-07 22.579530 3.521204 0.8290332000-01-08 4.577374 9.233151 0.466834

Boolean operators work as well:

In [97]: df1 = pd.DataFrame({'a': [1, 0, 1], 'b': [0, 1, 1]}, dtype=bool)In [98]: df2 = pd.DataFrame({'a': [0, 1, 1], 'b': [1, 1, 0]}, dtype=bool)In [99]: df1 & df2Out[99]:a b0 False False1 False True2 True FalseIn [100]: df1 | df2Out[100]:a b0 True True1 True True2 True TrueIn [101]: df1 ^ df2Out[101]:a b0 True True1 True False2 False TrueIn [102]: -df1Out[102]:a b0 False True1 True False2 False False

Transposing

To transpose, access the T attribute (also the transpose function), similar to an ndarray:

# only show the first 5 rowsIn [103]: df[:5].TOut[103]:2000-01-01 2000-01-02 2000-01-03 2000-01-04 2000-01-05A -1.226825 -0.727707 0.695775 -1.110336 -0.732339B 0.769804 -0.121306 0.341734 -0.619976 0.687738C -1.281247 -0.097883 0.959726 0.149748 0.176444

DataFrame interoperability with NumPy functions

Elementwise NumPy ufuncs (log, exp, sqrt, …) and various other NumPy functions can be used with no issues on DataFrame, assuming the data within are numeric:

In [104]: np.exp(df)Out[104]:A B C2000-01-01 0.293222 2.159342 0.2776912000-01-02 0.483015 0.885763 0.9067552000-01-03 2.005262 1.407386 2.6109802000-01-04 0.329448 0.537957 1.1615422000-01-05 0.480783 1.989212 1.1929682000-01-06 1.496770 0.856457 1.3520532000-01-07 0.113057 0.254145 0.3851172000-01-08 4.317584 0.174966 0.437538In [105]: np.asarray(df)Out[105]:array([[-1.2268, 0.7698, -1.2812],[-0.7277, -0.1213, -0.0979],[ 0.6958, 0.3417, 0.9597],[-1.1103, -0.62 , 0.1497],[-0.7323, 0.6877, 0.1764],[ 0.4033, -0.155 , 0.3016],[-2.1799, -1.3698, -0.9542],[ 1.4627, -1.7432, -0.8266]])

The dot method on DataFrame implements matrix multiplication:

In [106]: df.T.dot(df)Out[106]:A B CA 11.341858 -0.059772 3.007998B -0.059772 6.520556 2.083308C 3.007998 2.083308 4.310549

Similarly, the dot method on Series implements dot product:

In [107]: s1 = pd.Series(np.arange(5, 10))In [108]: s1.dot(s1)Out[108]: 255

DataFrame is not intended to be a drop-in replacement for ndarray as its indexing semantics are quite different in places from a matrix.

Console display

Very large DataFrames will be truncated to display them in the console. You can also get a summary using info(). (Here I am reading a CSV version of the baseball dataset from the plyr R package):

In [109]: baseball = pd.read_csv('data/baseball.csv')In [110]: print(baseball)id player year stint team lg g ab r h X2b X3b hr rbi sb cs bb so ibb hbp sh sf gidp0 88641 womacto01 2006 2 CHN NL 19 50 6 14 1 0 1 2.0 1.0 1.0 4 4.0 0.0 0.0 3.0 0.0 0.01 88643 schilcu01 2006 1 BOS AL 31 2 0 1 0 0 0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0 1.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0.. ... ... ... ... ... .. .. ... .. ... ... ... .. ... ... ... .. ... ... ... ... ... ...98 89533 aloumo01 2007 1 NYN NL 87 328 51 112 19 1 13 49.0 3.0 0.0 27 30.0 5.0 2.0 0.0 3.0 13.099 89534 alomasa02 2007 1 NYN NL 8 22 1 3 1 0 0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0 3.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0[100 rows x 23 columns]In [111]: baseball.info()<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>RangeIndex: 100 entries, 0 to 99Data columns (total 23 columns):id 100 non-null int64player 100 non-null objectyear 100 non-null int64stint 100 non-null int64team 100 non-null objectlg 100 non-null objectg 100 non-null int64ab 100 non-null int64r 100 non-null int64h 100 non-null int64X2b 100 non-null int64X3b 100 non-null int64hr 100 non-null int64rbi 100 non-null float64sb 100 non-null float64cs 100 non-null float64bb 100 non-null int64so 100 non-null float64ibb 100 non-null float64hbp 100 non-null float64sh 100 non-null float64sf 100 non-null float64gidp 100 non-null float64dtypes: float64(9), int64(11), object(3)memory usage: 18.0+ KB

However, using to_string will return a string representation of the DataFrame in tabular form, though it won’t always fit the console width:

In [112]: print(baseball.iloc[-20:, :12].to_string())id player year stint team lg g ab r h X2b X3b80 89474 finlest01 2007 1 COL NL 43 94 9 17 3 081 89480 embreal01 2007 1 OAK AL 4 0 0 0 0 082 89481 edmonji01 2007 1 SLN NL 117 365 39 92 15 283 89482 easleda01 2007 1 NYN NL 76 193 24 54 6 084 89489 delgaca01 2007 1 NYN NL 139 538 71 139 30 085 89493 cormirh01 2007 1 CIN NL 6 0 0 0 0 086 89494 coninje01 2007 2 NYN NL 21 41 2 8 2 087 89495 coninje01 2007 1 CIN NL 80 215 23 57 11 188 89497 clemero02 2007 1 NYA AL 2 2 0 1 0 089 89498 claytro01 2007 2 BOS AL 8 6 1 0 0 090 89499 claytro01 2007 1 TOR AL 69 189 23 48 14 091 89501 cirilje01 2007 2 ARI NL 28 40 6 8 4 092 89502 cirilje01 2007 1 MIN AL 50 153 18 40 9 293 89521 bondsba01 2007 1 SFN NL 126 340 75 94 14 094 89523 biggicr01 2007 1 HOU NL 141 517 68 130 31 395 89525 benitar01 2007 2 FLO NL 34 0 0 0 0 096 89526 benitar01 2007 1 SFN NL 19 0 0 0 0 097 89530 ausmubr01 2007 1 HOU NL 117 349 38 82 16 398 89533 aloumo01 2007 1 NYN NL 87 328 51 112 19 199 89534 alomasa02 2007 1 NYN NL 8 22 1 3 1 0

Wide DataFrames will be printed across multiple rows by default:

In [113]: pd.DataFrame(np.random.randn(3, 12))Out[113]:0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 110 -0.345352 1.314232 0.690579 0.995761 2.396780 0.014871 3.357427 -0.317441 -1.236269 0.896171 -0.487602 -0.0822401 -2.182937 0.380396 0.084844 0.432390 1.519970 -0.493662 0.600178 0.274230 0.132885 -0.023688 2.410179 1.4505202 0.206053 -0.251905 -2.213588 1.063327 1.266143 0.299368 -0.863838 0.408204 -1.048089 -0.025747 -0.988387 0.094055

You can change how much to print on a single row by setting the display.width option:

In [114]: pd.set_option('display.width', 40) # default is 80In [115]: pd.DataFrame(np.random.randn(3, 12))Out[115]:0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 110 1.262731 1.289997 0.082423 -0.055758 0.536580 -0.489682 0.369374 -0.034571 -2.484478 -0.281461 0.030711 0.1091211 1.126203 -0.977349 1.474071 -0.064034 -1.282782 0.781836 -1.071357 0.441153 2.353925 0.583787 0.221471 -0.7444712 0.758527 1.729689 -0.964980 -0.845696 -1.340896 1.846883 -1.328865 1.682706 -1.717693 0.888782 0.228440 0.901805

You can adjust the max width of the individual columns by setting display.max_colwidth

In [116]: datafile = {'filename': ['filename_01', 'filename_02'],.....: 'path': ["media/user_name/storage/folder_01/filename_01",.....: "media/user_name/storage/folder_02/filename_02"]}.....:In [117]: pd.set_option('display.max_colwidth', 30)In [118]: pd.DataFrame(datafile)Out[118]:filename path0 filename_01 media/user_name/storage/fo...1 filename_02 media/user_name/storage/fo...In [119]: pd.set_option('display.max_colwidth', 100)In [120]: pd.DataFrame(datafile)Out[120]:filename path0 filename_01 media/user_name/storage/folder_01/filename_011 filename_02 media/user_name/storage/folder_02/filename_02

You can also disable this feature via the expand_frame_repr option. This will print the table in one block.

DataFrame column attribute access and IPython completion

If a DataFrame column label is a valid Python variable name, the column can be accessed like an attribute:

In [121]: df = pd.DataFrame({'foo1': np.random.randn(5),.....: 'foo2': np.random.randn(5)}).....:In [122]: dfOut[122]:foo1 foo20 1.171216 -0.8584471 0.520260 0.3069962 -1.197071 -0.0286653 -1.066969 0.3843164 -0.303421 1.574159In [123]: df.foo1Out[123]:0 1.1712161 0.5202602 -1.1970713 -1.0669694 -0.303421Name: foo1, dtype: float64

The columns are also connected to the IPython completion mechanism so they can be tab-completed:

In [5]: df.fo<TAB> # noqa: E225, E999df.foo1 df.foo2

Panel

::: danger Warning

In 0.20.0, Panel is deprecated and will be removed in a future version. See the section Deprecate Panel.

:::

Panel is a somewhat less-used, but still important container for 3-dimensional data. The term panel data is derived from econometrics and is partially responsible for the name pandas: pan(el)-da(ta)-s. The names for the 3 axes are intended to give some semantic meaning to describing operations involving panel data and, in particular, econometric analysis of panel data. However, for the strict purposes of slicing and dicing a collection of DataFrame objects, you may find the axis names slightly arbitrary:

- items: axis 0, each item corresponds to a DataFrame contained inside

- major_axis: axis 1, it is the index (rows) of each of the DataFrames

- minor_axis: axis 2, it is the columns of each of the DataFrames

Construction of Panels works about like you would expect:

From 3D ndarray with optional axis labels

In [124]: wp = pd.Panel(np.random.randn(2, 5, 4), items=['Item1', 'Item2'],.....: major_axis=pd.date_range('1/1/2000', periods=5),.....: minor_axis=['A', 'B', 'C', 'D']).....:In [125]: wpOut[125]:<class 'pandas.core.panel.Panel'>Dimensions: 2 (items) x 5 (major_axis) x 4 (minor_axis)Items axis: Item1 to Item2Major_axis axis: 2000-01-01 00:00:00 to 2000-01-05 00:00:00Minor_axis axis: A to D

From dict of DataFrame objects

In [126]: data = {'Item1': pd.DataFrame(np.random.randn(4, 3)),.....: 'Item2': pd.DataFrame(np.random.randn(4, 2))}.....:In [127]: pd.Panel(data)Out[127]:<class 'pandas.core.panel.Panel'>Dimensions: 2 (items) x 4 (major_axis) x 3 (minor_axis)Items axis: Item1 to Item2Major_axis axis: 0 to 3Minor_axis axis: 0 to 2

Note that the values in the dict need only be convertible to DataFrame. Thus, they can be any of the other valid inputs to DataFrame as per above.

One helpful factory method is Panel.from_dict, which takes a dictionary of DataFrames as above, and the following named parameters:

| Parameter | Default | Description |

|---|---|---|

| intersect | False | drops elements whose indices do not align |

| orient | items | use minor to use DataFrames’ columns as panel items |

For example, compare to the construction above:

In [128]: pd.Panel.from_dict(data, orient='minor')Out[128]:<class 'pandas.core.panel.Panel'>Dimensions: 3 (items) x 4 (major_axis) x 2 (minor_axis)Items axis: 0 to 2Major_axis axis: 0 to 3Minor_axis axis: Item1 to Item2

Orient is especially useful for mixed-type DataFrames. If you pass a dict of DataFrame objects with mixed-type columns, all of the data will get upcasted to dtype=object unless you pass orient='minor':

In [129]: df = pd.DataFrame({'a': ['foo', 'bar', 'baz'],.....: 'b': np.random.randn(3)}).....:In [130]: dfOut[130]:a b0 foo -0.3088531 bar -0.6810872 baz 0.377953In [131]: data = {'item1': df, 'item2': df}In [132]: panel = pd.Panel.from_dict(data, orient='minor')In [133]: panel['a']Out[133]:item1 item20 foo foo1 bar bar2 baz bazIn [134]: panel['b']Out[134]:item1 item20 -0.308853 -0.3088531 -0.681087 -0.6810872 0.377953 0.377953In [135]: panel['b'].dtypesOut[135]:item1 float64item2 float64dtype: object

::: tip Note Panel, being less commonly used than Series and DataFrame, has been slightly neglected feature-wise. A number of methods and options available in DataFrame are not available in Panel. :::

From DataFrame using to_panel method

to_panel converts a DataFrame with a two-level index to a Panel.

In [136]: midx = pd.MultiIndex(levels=[['one', 'two'], ['x', 'y']],.....: codes=[[1, 1, 0, 0], [1, 0, 1, 0]]).....:In [137]: df = pd.DataFrame({'A': [1, 2, 3, 4], 'B': [5, 6, 7, 8]}, index=midx)In [138]: df.to_panel()Out[138]:<class 'pandas.core.panel.Panel'>Dimensions: 2 (items) x 2 (major_axis) x 2 (minor_axis)Items axis: A to BMajor_axis axis: one to twoMinor_axis axis: x to y

Item selection / addition / deletion

Similar to DataFrame functioning as a dict of Series, Panel is like a dict of DataFrames:

In [139]: wp['Item1']Out[139]:A B C D2000-01-01 1.588931 0.476720 0.473424 -0.2428612000-01-02 -0.014805 -0.284319 0.650776 -1.4616652000-01-03 -1.137707 -0.891060 -0.693921 1.6136162000-01-04 0.464000 0.227371 -0.496922 0.3063892000-01-05 -2.290613 -1.134623 -1.561819 -0.260838In [140]: wp['Item3'] = wp['Item1'] / wp['Item2']

The API for insertion and deletion is the same as for DataFrame. And as with DataFrame, if the item is a valid Python identifier, you can access it as an attribute and tab-complete it in IPython.

Transposing

A Panel can be rearranged using its transpose method (which does not make a copy by default unless the data are heterogeneous):

In [141]: wp.transpose(2, 0, 1)Out[141]:<class 'pandas.core.panel.Panel'>Dimensions: 4 (items) x 3 (major_axis) x 5 (minor_axis)Items axis: A to DMajor_axis axis: Item1 to Item3Minor_axis axis: 2000-01-01 00:00:00 to 2000-01-05 00:00:00

Indexing / Selection

| Operation | Syntax | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Select item | wp[item] | DataFrame |

| Get slice at major_axis label | wp.major_xs(val) | DataFrame |

| Get slice at minor_axis label | wp.minor_xs(val) | DataFrame |

For example, using the earlier example data, we could do:

In [142]: wp['Item1']Out[142]:A B C D2000-01-01 1.588931 0.476720 0.473424 -0.2428612000-01-02 -0.014805 -0.284319 0.650776 -1.4616652000-01-03 -1.137707 -0.891060 -0.693921 1.6136162000-01-04 0.464000 0.227371 -0.496922 0.3063892000-01-05 -2.290613 -1.134623 -1.561819 -0.260838In [143]: wp.major_xs(wp.major_axis[2])Out[143]:Item1 Item2 Item3A -1.137707 0.800193 -1.421791B -0.891060 0.782098 -1.139320C -0.693921 -1.069094 0.649074D 1.613616 -1.099248 -1.467927In [144]: wp.minor_axisOut[144]: Index(['A', 'B', 'C', 'D'], dtype='object')In [145]: wp.minor_xs('C')Out[145]:Item1 Item2 Item32000-01-01 0.473424 -0.902937 -0.5243162000-01-02 0.650776 -1.144073 -0.5688242000-01-03 -0.693921 -1.069094 0.6490742000-01-04 -0.496922 0.661084 -0.7516782000-01-05 -1.561819 -1.056652 1.478083

Squeezing

Another way to change the dimensionality of an object is to squeeze a 1-len object, similar to wp['Item1'].

In [146]: wp.reindex(items=['Item1']).squeeze()Out[146]:A B C D2000-01-01 1.588931 0.476720 0.473424 -0.2428612000-01-02 -0.014805 -0.284319 0.650776 -1.4616652000-01-03 -1.137707 -0.891060 -0.693921 1.6136162000-01-04 0.464000 0.227371 -0.496922 0.3063892000-01-05 -2.290613 -1.134623 -1.561819 -0.260838In [147]: wp.reindex(items=['Item1'], minor=['B']).squeeze()Out[147]:2000-01-01 0.4767202000-01-02 -0.2843192000-01-03 -0.8910602000-01-04 0.2273712000-01-05 -1.134623Freq: D, Name: B, dtype: float64

Conversion to DataFrame

A Panel can be represented in 2D form as a hierarchically indexed DataFrame. See the section hierarchical indexing for more on this. To convert a Panel to a DataFrame, use the to_frame method:

In [148]: panel = pd.Panel(np.random.randn(3, 5, 4), items=['one', 'two', 'three'],.....: major_axis=pd.date_range('1/1/2000', periods=5),.....: minor_axis=['a', 'b', 'c', 'd']).....:In [149]: panel.to_frame()Out[149]:one two threemajor minor2000-01-01 a 0.493672 1.219492 -1.290493b -2.461467 0.062297 0.787872c -1.553902 -0.110388 1.515707d 2.015523 -1.184357 -0.2764872000-01-02 a -1.833722 -0.558081 -0.223762b 1.771740 0.077849 1.397431c -0.670027 0.629498 1.503874d 0.049307 -1.035260 -0.4789052000-01-03 a -0.521493 -0.438229 -0.135950b -3.201750 0.503703 -0.730327c 0.792716 0.413086 -0.033277d 0.146111 -1.139050 0.2811512000-01-04 a 1.903247 0.660342 -1.298915b -0.747169 0.464794 -2.819487c -0.309038 -0.309337 -0.851985d 0.393876 -0.649593 -1.1069522000-01-05 a 1.861468 0.683758 -0.937731b 0.936527 -0.643834 -1.537770c 1.255746 0.421287 0.555759d -2.655452 1.032814 -2.277282

Deprecate Panel

Over the last few years, pandas has increased in both breadth and depth, with new features, datatype support, and manipulation routines. As a result, supporting efficient indexing and functional routines for Series, DataFrame and Panel has contributed to an increasingly fragmented and difficult-to-understand code base.

The 3-D structure of a Panel is much less common for many types of data analysis, than the 1-D of the Series or the 2-D of the DataFrame. Going forward it makes sense for pandas to focus on these areas exclusively.

Oftentimes, one can simply use a MultiIndex DataFrame for easily working with higher dimensional data.

In addition, the xarray package was built from the ground up, specifically in order to support the multi-dimensional analysis that is one of Panel s main use cases. Here is a link to the xarray panel-transition documentation.

In [150]: import pandas.util.testing as tmIn [151]: p = tm.makePanel()In [152]: pOut[152]:<class 'pandas.core.panel.Panel'>Dimensions: 3 (items) x 30 (major_axis) x 4 (minor_axis)Items axis: ItemA to ItemCMajor_axis axis: 2000-01-03 00:00:00 to 2000-02-11 00:00:00Minor_axis axis: A to D

Convert to a MultiIndex DataFrame.

In [153]: p.to_frame()Out[153]:ItemA ItemB ItemCmajor minor2000-01-03 A -0.390201 -1.624062 -0.605044B 1.562443 0.483103 0.583129C -1.085663 0.768159 -0.273458D 0.136235 -0.021763 -0.7006482000-01-04 A 1.207122 -0.758514 0.878404B 0.763264 0.061495 -0.876690C -1.114738 0.225441 -0.335117D 0.886313 -0.047152 -1.1666072000-01-05 A 0.178690 -0.560859 -0.921485B 0.162027 0.240767 -1.919354C -0.058216 0.543294 -0.476268D -1.350722 0.088472 -0.3672362000-01-06 A -1.004168 -0.589005 -0.200312B -0.902704 0.782413 -0.572707C -0.486768 0.771931 -1.765602D -0.886348 -0.857435 1.2966742000-01-07 A -1.377627 -1.070678 0.522423B 1.106010 0.628462 -1.736484C 1.685148 -0.968145 0.578223D -1.013316 -2.503786 0.6413852000-01-10 A 0.499281 -1.681101 0.722511B -0.199234 -0.880627 -1.335113C 0.112572 -1.176383 0.242697D 1.920906 -1.058041 -0.7794322000-01-11 A -1.405256 0.403776 -1.702486B 0.458265 0.777575 -1.244471C -1.495309 -3.192716 0.208129D -0.388231 -0.657981 0.6024562000-01-12 A 0.162565 0.609862 -0.709535B 0.491048 -0.779367 0.347339... ... ... ...2000-02-02 C -0.303961 -0.463752 -0.288962D 0.104050 1.116086 0.5064452000-02-03 A -2.338595 -0.581967 -0.801820B -0.557697 -0.033731 -0.176382C 0.625555 -0.055289 0.875359D 0.174068 -0.443915 1.6263692000-02-04 A -0.374279 -1.233862 -0.915751B 0.381353 -1.108761 -1.970108C -0.059268 -0.360853 -0.614618D -0.439461 -0.200491 0.4295182000-02-07 A -2.359958 -3.520876 -0.288156B 1.337122 -0.314399 -1.044208C 0.249698 0.728197 0.565375D -0.741343 1.092633 0.0139102000-02-08 A -1.157886 0.516870 -1.199945B -1.531095 -0.860626 -0.821179C 1.103949 1.326768 0.068184D -0.079673 -1.675194 -0.4582722000-02-09 A -0.551865 0.343125 -0.072869B 1.331458 0.370397 -1.914267C -1.087532 0.208927 0.788871D -0.922875 0.437234 -1.5310042000-02-10 A 1.592673 2.137827 -1.828740B -0.571329 -1.761442 -0.826439C 1.998044 0.292058 -0.280343D 0.303638 0.388254 -0.5005692000-02-11 A 1.559318 0.452429 -1.716981B -0.026671 -0.899454 0.124808C -0.244548 -2.019610 0.931536D -0.917368 0.479630 0.870690[120 rows x 3 columns]

Alternatively, one can convert to an xarray DataArray.

In [154]: p.to_xarray()Out[154]:<xarray.DataArray (items: 3, major_axis: 30, minor_axis: 4)>array([[[-0.390201, 1.562443, -1.085663, 0.136235],[ 1.207122, 0.763264, -1.114738, 0.886313],...,[ 1.592673, -0.571329, 1.998044, 0.303638],[ 1.559318, -0.026671, -0.244548, -0.917368]],[[-1.624062, 0.483103, 0.768159, -0.021763],[-0.758514, 0.061495, 0.225441, -0.047152],...,[ 2.137827, -1.761442, 0.292058, 0.388254],[ 0.452429, -0.899454, -2.01961 , 0.47963 ]],[[-0.605044, 0.583129, -0.273458, -0.700648],[ 0.878404, -0.87669 , -0.335117, -1.166607],...,[-1.82874 , -0.826439, -0.280343, -0.500569],[-1.716981, 0.124808, 0.931536, 0.87069 ]]])Coordinates:* items (items) object 'ItemA' 'ItemB' 'ItemC'* major_axis (major_axis) datetime64[ns] 2000-01-03 2000-01-04 ... 2000-02-11* minor_axis (minor_axis) object 'A' 'B' 'C' 'D'

You can see the full-documentation for the xarray package.