6. Partitioning

Clearly, we must break away from the sequential and not limit the computers. We must state definitions and provide for priorities and descriptions of data. We must state relation‐ ships, not procedures.

— Grace Murray Hopper, Management and the Computer of the Future (1962)

In Chapter 5 we discussed replication—that is, having multiple copies of the same data on different nodes. For very large datasets, or very high query throughput, that is not sufficient: we need to break the data up into partitions, also known as sharding.[^i]

[^i]: Partitioning, as discussed in this chapter, is a way of intentionally breaking a large database down into smaller ones. It has nothing to do with network partitions (netsplits), a type of fault in the network between nodes. We will discuss such faults in Chapter 8.

Terminological confusion

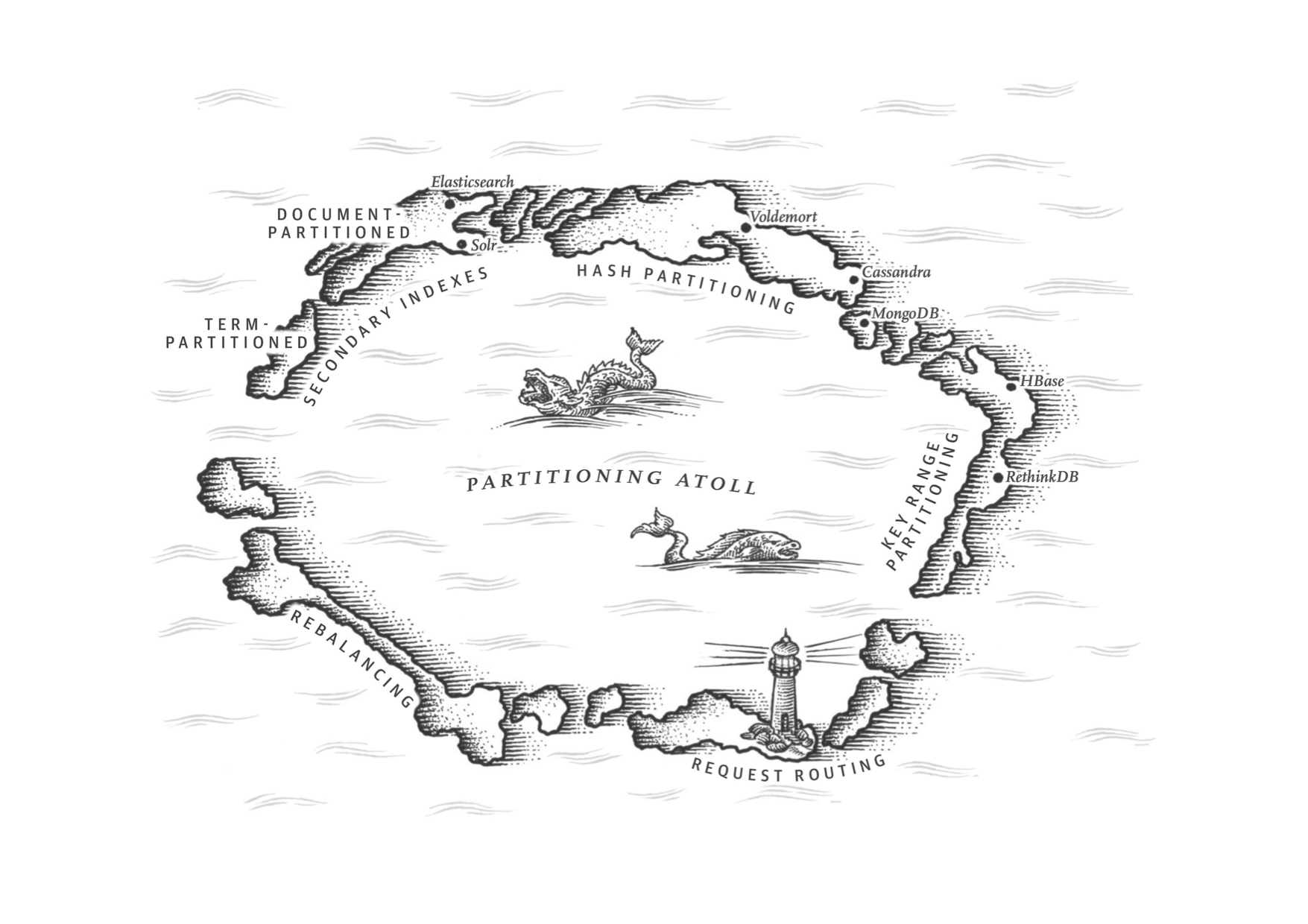

What we call a partition here is called a shard in MongoDB, Elasticsearch, and SolrCloud; it’s known as a region in HBase, a tablet in Bigtable, a vnode in Cassandra and Riak, and a vBucket in Couchbase. However, partitioning is the most established term, so we’ll stick with that.

Normally, partitions are defined in such a way that each piece of data (each record, row, or document) belongs to exactly one partition. There are various ways of achiev‐ ing this, which we discuss in depth in this chapter. In effect, each partition is a small database of its own, although the database may support operations that touch multi‐ ple partitions at the same time.

The main reason for wanting to partition data is scalability. Different partitions can be placed on different nodes in a shared-nothing cluster (see the introduction to Part II for a definition of shared nothing). Thus, a large dataset can be distributed across many disks, and the query load can be distributed across many processors.

For queries that operate on a single partition, each node can independently execute the queries for its own partition, so query throughput can be scaled by adding more nodes. Large, complex queries can potentially be parallelized across many nodes, although this gets significantly harder.

Partitioned databases were pioneered in the 1980s by products such as Teradata and Tandem NonStop SQL [1], and more recently rediscovered by NoSQL databases and Hadoop-based data warehouses. Some systems are designed for transactional work‐ loads, and others for analytics (see “Transaction Processing or Analytics?”): this difference affects how the system is tuned, but the fundamentals of partitioning apply to both kinds of workloads.

In this chapter we will first look at different approaches for partitioning large datasets and observe how the indexing of data interacts with partitioning. We’ll then talk about rebalancing, which is necessary if you want to add or remove nodes in your cluster. Finally, we’ll get an overview of how databases route requests to the right partitions and execute queries.

……

Summary

In this chapter we explored different ways of partitioning a large dataset into smaller subsets. Partitioning is necessary when you have so much data that storing and pro‐ cessing it on a single machine is no longer feasible.

The goal of partitioning is to spread the data and query load evenly across multiple machines, avoiding hot spots (nodes with disproportionately high load). This requires choosing a partitioning scheme that is appropriate to your data, and reba‐ lancing the partitions when nodes are added to or removed from the cluster.

We discussed two main approaches to partitioning:

Key range partitioning, where keys are sorted, and a partition owns all the keys from some minimum up to some maximum. Sorting has the advantage that effi‐ cient range queries are possible, but there is a risk of hot spots if the application often accesses keys that are close together in the sorted order.

In this approach, partitions are typically rebalanced dynamically by splitting the range into two subranges when a partition gets too big.

Hash partitioning, where a hash function is applied to each key, and a partition owns a range of hashes. This method destroys the ordering of keys, making range queries inefficient, but may distribute load more evenly.

When partitioning by hash, it is common to create a fixed number of partitions in advance, to assign several partitions to each node, and to move entire parti‐ tions from one node to another when nodes are added or removed. Dynamic partitioning can also be used.

Hybrid approaches are also possible, for example with a compound key: using one part of the key to identify the partition and another part for the sort order.

We also discussed the interaction between partitioning and secondary indexes. A sec‐ ondary index also needs to be partitioned, and there are two methods:

Document-partitioned indexes (local indexes), where the secondary indexes are stored in the same partition as the primary key and value. This means that only a single partition needs to be updated on write, but a read of the secondary index requires a scatter/gather across all partitions.

Term-partitioned indexes (global indexes), where the secondary indexes are partitioned separately, using the indexed values. An entry in the secondary index may include records from all partitions of the primary key. When a document is writ‐ ten, several partitions of the secondary index need to be updated; however, a read can be served from a single partition.

Finally, we discussed techniques for routing queries to the appropriate partition, which range from simple partition-aware load balancing to sophisticated parallel query execution engines.

By design, every partition operates mostly independently—that’s what allows a parti‐ tioned database to scale to multiple machines. However, operations that need to write to several partitions can be difficult to reason about: for example, what happens if the write to one partition succeeds, but another fails? We will address that question in the following chapters.

References

David J. DeWitt and Jim N. Gray: “Parallel Database Systems: The Future of High Performance Database Systems,” Communications of the ACM, volume 35, number 6, pages 85–98, June 1992. doi:10.1145/129888.129894

Lars George: “HBase vs. BigTable Comparison,” larsgeorge.com, November 2009.

“The Apache HBase Reference Guide,” Apache Software Foundation, hbase.apache.org, 2014.

MongoDB, Inc.: “New Hash-Based Sharding Feature in MongoDB 2.4,” blog.mongodb.org, April 10, 2013.

Ikai Lan: “App Engine Datastore Tip: Monotonically Increasing Values Are Bad,” ikaisays.com, January 25, 2011.

Martin Kleppmann: “Java’s hashCode Is Not Safe for Distributed Systems,” martin.kleppmann.com, June 18, 2012.

David Karger, Eric Lehman, Tom Leighton, et al.: “Consistent Hashing and Random Trees: Distributed Caching Protocols for Relieving Hot Spots on the World Wide Web,” at 29th Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing (STOC), pages 654–663, 1997. doi:10.1145/258533.258660

John Lamping and Eric Veach: “A Fast, Minimal Memory, Consistent Hash Algorithm,” arxiv.org, June 2014.

Eric Redmond: “A Little Riak Book,” Version 1.4.0, Basho Technologies, September 2013.

“Couchbase 2.5 Administrator Guide,” Couchbase, Inc., 2014.

Avinash Lakshman and Prashant Malik: “Cassandra – A Decentralized Structured Storage System,” at 3rd ACM SIGOPS International Workshop on Large Scale Distributed Systems and Middleware (LADIS), October 2009.

Jonathan Ellis: “Facebook’s Cassandra Paper, Annotated and Compared to Apache Cassandra 2.0,” datastax.com, September 12, 2013.

“Introduction to Cassandra Query Language,” DataStax, Inc., 2014.

Samuel Axon: “3% of Twitter’s Servers Dedicated to Justin Bieber,” mashable.com, September 7, 2010.

“Riak 1.4.8 Docs,” Basho Technologies, Inc., 2014.

Richard Low: “The Sweet Spot for Cassandra Secondary Indexing,” wentnet.com, October 21, 2013.

Zachary Tong: “Customizing Your Document Routing,” elasticsearch.org, June 3, 2013.

“Apache Solr Reference Guide,” Apache Software Foundation, 2014.

Andrew Pavlo: “H-Store Frequently Asked Questions,” hstore.cs.brown.edu, October 2013.

“Amazon DynamoDB Developer Guide,” Amazon Web Services, Inc., 2014.

Rusty Klophaus: “Difference Between 2I and Search,” email to riak-users mailing list, lists.basho.com, October 25, 2011.

Donald K. Burleson: “Object Partitioning in Oracle,”dba-oracle.com, November 8, 2000.

Eric Evans: “Rethinking Topology in Cassandra,” at ApacheCon Europe, November 2012.

Rafał Kuć: “Reroute API Explained,” elasticsearchserverbook.com, September 30, 2013.

“Project Voldemort Documentation,” project-voldemort.com.

Enis Soztutar: “Apache HBase Region Splitting and Merging,” hortonworks.com, February 1, 2013.

Brandon Williams: “Virtual Nodes in Cassandra 1.2,” datastax.com, December 4, 2012.

Richard Jones: “libketama: Consistent Hashing Library for Memcached Clients,” metabrew.com, April 10, 2007.

Branimir Lambov: “New Token Allocation Algorithm in Cassandra 3.0,” datastax.com, January 28, 2016.

Jason Wilder: “Open-Source Service Discovery,” jasonwilder.com, February 2014.

Kishore Gopalakrishna, Shi Lu, Zhen Zhang, et al.: “Untangling Cluster Management with Helix,” at ACM Symposium on Cloud Computing (SoCC), October 2012. doi:10.1145/2391229.2391248

“Moxi 1.8 Manual,” Couchbase, Inc., 2014.

Shivnath Babu and Herodotos Herodotou: “Massively Parallel Databases and MapReduce Systems,” Foundations and Trends in Databases, volume 5, number 1, pages 1–104, November 2013.doi:10.1561/1900000036