- By Pieter Hintjens, CEO of iMatix

- ZeroMQ 简介

- 它如何开始

- Zero的含义

- Audience

- 致谢

- Chapter 1 - Basics

- Chapter 2 - Sockets and Patterns

- The Socket API

- 将Sockets插入拓扑中

- 发送和接收消息

- 单播传输(Unicast Transports)

- ZeroMQ 不是中立的载体(Neutral Carrier)

- I/O Threads

- 消息传递模式(Messaging Patterns)

- High-Level Messaging Patterns

- 处理消息(Working with Messages)

- 处理多个Sockets(Handling Multiple Sockets)

- 多部分消息(Multipart Messages)

- 中介和代理 Intermediaries and Proxies

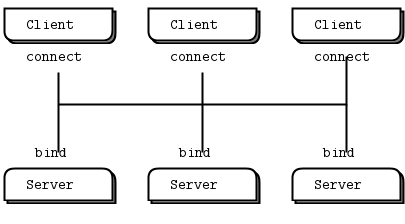

- 动态发现问题 The Dynamic Discovery Problem

- 共享队列Shared Queue (DEALER and ROUTER sockets)

- ZeroMQ的内置代理函数 ZeroMQ’s Built-In Proxy Function

- 传输桥接 Transport Bridging

- 处理错误和黑屏? Handling Errors and ETERM

- 处理中断信号 Handling Interrupt Signals

- 检测内存泄漏 Detecting Memory Leaks

- 多线程与ZeroMQMultithreading with ZeroMQ

- 线程之间的通信Signaling Between Threads (PAIR Sockets)

- 节点的协调Node Coordination

- 零拷贝Zero-Copy

- 发布-订阅消息信封Pub-Sub Message Envelopes

- High-Water Marks

- 缺少消息问题的解决者(解决方式)Missing Message Problem Solver

- Chapter 3 -高级 Advanced Request-Reply Patterns

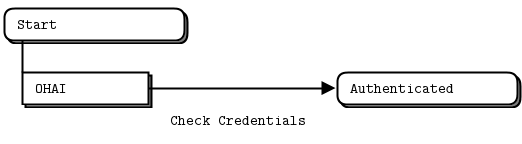

- The Request-Reply Mechanisms(机制)

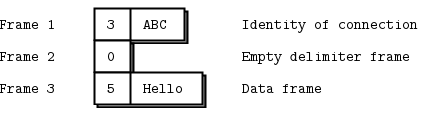

- The Simple Reply Envelope

- 加长回信信封The Extended Reply Envelope

- What’s This Good For?

- (概述)Recap of Request-Reply Sockets

- Request-Reply Combinations(组合)

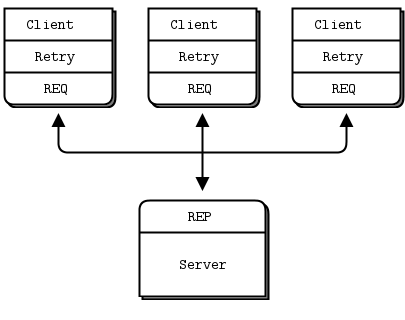

- The REQ to REP Combination

- The DEALER to REP Combination

- The REQ to ROUTER Combination

- The DEALER to DEALER Combination

- Invalid Combinations

- 探索Exploring ROUTER Sockets

- 负载平衡模式The Load Balancing Pattern

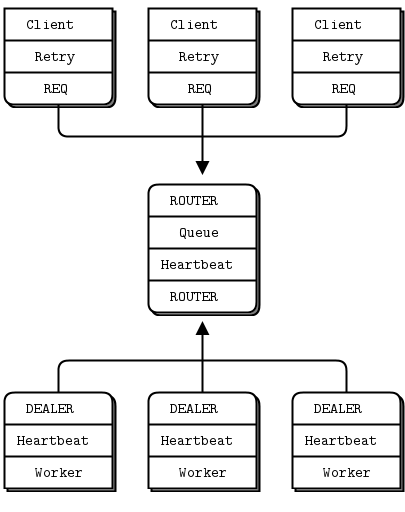

- 负载平衡消息代理 A Load Balancing Message Broker

- 异步客户端/服务器模式The Asynchronous Client/Server Pattern

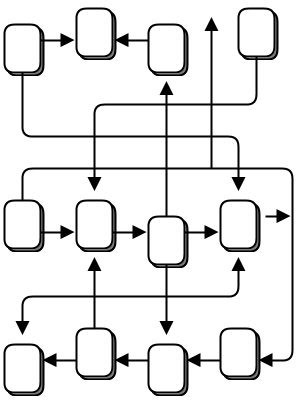

- Worked Example: Inter-Broker Routing

- Chapter 4 - Reliable Request-Reply Patterns

- Chapter 8 -分布式计算框架 A Framework for Distributed Computing

ØMQ - The Guide

By Pieter Hintjens, CEO of iMatix

Please use the issue tracker for all comments and errata. This version covers the latest stable release of ZeroMQ (3.2). If you are using older versions of ZeroMQ then some of the examples and explanations won’t be accurate.

The Guide is originally in C, but also in PHP, Java, Python, Lua, and Haxe. We’ve also translated most of the examples into C++, C#, CL, Delphi, Erlang, F#, Felix, Haskell, Objective-C, Ruby, Ada, Basic, Clojure, Go, Haxe, Node.js, ooc, Perl, and Scala.

ZeroMQ 简介

ZeroMQ(也称为ØMQ, 0mq或zmq)看起来像一个嵌入式的网络库(an embeddable networking library),但就像一个并发性框架。它为您提供了scoket,可以跨进程内、进程间、TCP和多播等各种传输传输原子消息。您可以N-to-N的连接scokets 诸如 fan-out, pub-sub, task distribution,和request-reply等模式。它的速度足以成为集群产品的组织(fabric)。它的异步I/O模型为您提供了可伸缩的多核应用程序,构建为异步消息处理任务。它有大量的语言api,可以在大多数操作系统上运行。ZeroMQ来自iMatix,是LGPLv3级开源。

它如何开始

We took a normal TCP socket, injected it with a mix of radioactive isotopes stolen from a secret Soviet atomic research project, bombarded it with 1950-era cosmic rays, and put it into the hands of a drug-addled comic book author with a badly-disguised fetish for bulging muscles clad in spandex. Yes, ZeroMQ sockets are the world-saving superheroes of the networking world.

Figure 1 - A terrible accident…

Zero的含义

ZeroMQ的Ø权衡。一方面,这个奇怪的名字降低了ZeroMQ在谷歌和Twitter上的知名度。另一方面它惹恼了我们丹麦人写一些诸如“ØMG røtfl”,并且“Ø看作(looking)零不是好笑的!”和“地中海Rødgrød fløde !”,这显然是一种侮辱,意思是“愿你的邻居是格伦德尔的直系后裔!”似乎是公平交易。

最初ZeroMQ中的0表示“零代理”,并且(接近于)“零延迟”(尽可能)。从那时起,它开始包含不同的目标:零管理、零成本、零浪费。更普遍地说,“零”指的是渗透在项目中的极简主义文化。我们通过消除复杂性而不是公开新功能来增加功能。

Audience

本书是为专业程序员编写的,他们想要学习如何制作将主导未来计算的大规模分布式软件。我们假设您可以阅读C代码,因为这里的大多数示例都是用C编写的,即使ZeroMQ在许多语言中都被使用。我们假设您关心规模,因为ZeroMQ首先解决了这个问题。我们假设您需要以尽可能少的成本获得尽可能好的结果,否则您将不会欣赏ZeroMQ所做的权衡。除了基本的背景知识,我们还将介绍使用ZeroMQ所需的网络和分布式计算的所有概念。

致谢

Thanks to Andy Oram for making the O’Reilly book happen, and editing this text.

Thanks to Bill Desmarais, Brian Dorsey, Daniel Lin, Eric Desgranges, Gonzalo Diethelm, Guido Goldstein, Hunter Ford, Kamil Shakirov, Martin Sustrik, Mike Castleman, Naveen Chawla, Nicola Peduzzi, Oliver Smith, Olivier Chamoux, Peter Alexander, Pierre Rouleau, Randy Dryburgh, John Unwin, Alex Thomas, Mihail Minkov, Jeremy Avnet, Michael Compton, Kamil Kisiel, Mark Kharitonov, Guillaume Aubert, Ian Barber, Mike Sheridan, Faruk Akgul, Oleg Sidorov, Lev Givon, Allister MacLeod, Alexander D’Archangel, Andreas Hoelzlwimmer, Han Holl, Robert G. Jakabosky, Felipe Cruz, Marcus McCurdy, Mikhail Kulemin, Dr. Gergő Érdi, Pavel Zhukov, Alexander Else, Giovanni Ruggiero, Rick “Technoweenie”, Daniel Lundin, Dave Hoover, Simon Jefford, Benjamin Peterson, Justin Case, Devon Weller, Richard Smith, Alexander Morland, Wadim Grasza, Michael Jakl, Uwe Dauernheim, Sebastian Nowicki, Simone Deponti, Aaron Raddon, Dan Colish, Markus Schirp, Benoit Larroque, Jonathan Palardy, Isaiah Peng, Arkadiusz Orzechowski, Umut Aydin, Matthew Horsfall, Jeremy W. Sherman, Eric Pugh, Tyler Sellon, John E. Vincent, Pavel Mitin, Min RK, Igor Wiedler, Olof Åkesson, Patrick Lucas, Heow Goodman, Senthil Palanisami, John Gallagher, Tomas Roos, Stephen McQuay, Erik Allik, Arnaud Cogoluègnes, Rob Gagnon, Dan Williams, Edward Smith, James Tucker, Kristian Kristensen, Vadim Shalts, Martin Trojer, Tom van Leeuwen, Hiten Pandya, Harm Aarts, Marc Harter, Iskren Ivov Chernev, Jay Han, Sonia Hamilton, Nathan Stocks, Naveen Palli, and Zed Shaw for their contributions to this work.

Chapter 1 - Basics

Fixing the World

如何解释ZeroMQ?我们中的一些人从它所做的所有奇妙的事情开始说起。它的sockets在steroids上。它就像带有路由的邮箱。它很快! 其他人试图分享他们的顿悟时刻,即当一切都变得显而易见时,ap-pow-kaboom satori paradigm-shift moment。事情变得简单了。复杂性消失。它能开阔思维。*其他人试图通过比较来解释。它更小、更简单,但看起来仍然很眼熟。就我个人而言,我想要记住我们为什么要制作ZeroMQ,因为这很有可能就是你们读者今天仍然在做的事情。

编程是一门伪装成艺术的科学,因为我们大多数人都不懂软件的物理原理,而且很少有人教过编程。 软件的物理不是算法、数据结构、语言和抽象。这些只是我们制造、使用、丢弃的工具。软件真正的物理特性是人的物理特性——具体地说,是我们在复杂性方面的局限性,以及我们合作解决大问题的愿望。这是编程的科学:制作人们能够理解和使用的积木,然后人们将一起工作来解决最大的问题。

我们生活在一个互联的世界,现代软件必须在这个世界中导航。因此,未来最大的解决方案的构建模块是相互连接和大规模并行的。仅仅让代码变得“强大而安静”是不够的。代码必须与代码对话。代码必须健谈、善于交际、关系良好。代码必须像人脑一样运行,数以万亿计的单个神经元相互发送信息,这是一个大规模的并行网络,没有中央控制,没有单点故障,但能够解决极其困难的问题。代码的未来看起来像人脑,这并非偶然,因为每个网络的端点,在某种程度上,都是人脑。

如果您使用线程、协议或网络做过任何工作,您就会发现这几乎是不可能的。这是一个梦。当您开始处理实际的情况时,即使跨几个scoket连接几个程序也是非常麻烦的。数万亿吗?其代价将是难以想象的。连接计算机是如此困难,以至于软件和服务要做这是一项数十亿美元的业务。

所以我们生活在一个线路比我们使用它的能力超前数年的世界里。上世纪80年代,我们经历了一场软件危机。当时,弗雷德•布鲁克斯(Fred Brooks)等顶尖软件工程师相信,没有什么“灵丹妙药”能“保证生产率、可靠性或简单性哪怕提高一个数量级”。

布鲁克斯错过了免费和开源软件,正是这些软件解决了这场危机,使我们能够有效地共享知识。今天,我们面临着另一场软件危机,但我们很少谈论它。只有最大、最富有的公司才有能力创建连接的应用程序。有云,但它是私有的。我们的数据和知识正在从个人电脑上消失,变成我们无法访问、无法与之竞争的云。谁拥有我们的社交网络?这就像是反过来的大型机- pc革命。

我们可以把政治哲学留给另一本书。关键是,互联网提供了大量的潜在连接代码,现实情况是,对于大多数人来说,这是难以企及的,所以巨大而有趣的问题(在健康、教育、经济、交通、等等)仍然没有解决,因为没有办法连接代码,因此没有办法去连接可以一起工作的大脑来解决这些问题。

已经有很多尝试来解决连接代码的挑战。有数以千计的IETF规范,每个规范都解决了这个难题的一部分。对于应用程序开发人员来说,HTTP可能是一个简单到足以工作的解决方案,但是它鼓励开发人员和架构师从大服务器和thin,stupid的客户机的角度考虑问题,从而使问题变得更糟。

因此,今天人们仍然使用原始UDP和TCP、专有协议、HTTP和Websockets连接应用程序。它仍然痛苦、缓慢、难以扩展,而且本质上是集中的。分布式P2P架构主要是为了玩,而不是工作。有多少应用程序使用Skype或Bittorrent来交换数据?

这让我们回到编程科学。要改变世界,我们需要做两件事。第一,解决“如何在任何地方将任何代码连接到任何代码”的一般问题。第二,用最简单的模块来概括,让人们能够理解和使用。

这听起来简单得可笑。也许确实如此。这就是重点。

开始的前提

我们假设您至少使用了ZeroMQ的3.2版。我们假设您正在使用Linux机器或类似的东西。我们假设您可以或多或少地阅读C代码,因为这是示例的默认语言。我们假设,当我们编写像PUSH或SUBSCRIBE这样的常量时,您可以想象它们实际上被称为’ ZMQ_PUSH ‘或’ ZMQ_SUBSCRIBE ‘(如果编程语言需要的话)。

获取例子

The examples live in a public GitHub repository. The simplest way to get all the examples is to clone this repository:

git clone --depth=1 https://github.com/imatix/zguide.git

接下来,浏览examples子目录。你会通过语言找到例子。如果您使用的语言中缺少示例,建议您提交翻译。正是由于许多人的努力,这篇文章才变得如此有用。所有示例都是根据MIT/X11授权的。

有求必应

让我们从一些代码开始。当然,我们从Hello World的例子开始。我们将创建一个客户机和一个服务器。客户端向服务器发送“Hello”,服务器以“World”作为响应。这是C语言的服务器,它在端口5555上打开一个ZeroMQ scoket,读取请求,然后用“World”对每个请求进行响应:

hwserver: Hello World server in C

C++ | C# | Clojure | CL | Delphi | Erlang | F# | Felix | Go | Haskell | Haxe | Java | Lua | Node.js | Objective-C| Perl | PHP | Python | Q | Racket | Ruby | Scala | Tcl | Ada | Basic | ooc

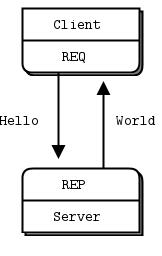

图2 - Request-Reply

REQ-REP套接字对是同步的。客户机在循环中发出zmq_send()然后zmq_recv(),在循环中(或者只需要执行一次)。执行任何其他序列(例如,在一行中发送两条消息)都会导致send或recv调用返回的代码为-1。类似地,服务按这个顺序发出zmq_recv()和zmq_send(),只要它需要。

ZeroMQ使用C作为参考语言,这是我们在示例中使用的主要语言。如果您正在在线阅读本文,下面的示例链接将带您到其他编程语言的翻译。让我们在c++中比较相同的服务器:

//Hello World server in C++//Binds REP socket to tcp://\*:5555//Expects "Hello" from client, replies with "World"//#include <zmq.hpp>#include <string>#include <iostream>#ifndef _WIN32#include <unistd.h>#else#include <windows.h>#define sleep(n) Sleep(n)#endifint main () {` `*// Prepare our context and socket*` `zmq::context_t context (1);` `zmq::socket_t socket (context, ZMQ_REP);` `socket.bind ("tcp://*:5555");` `**while** (true) {` `zmq::message_t request;` `*// Wait for next request from client*` `socket.recv (&request);` `std::cout << "Received Hello" << std::endl;` `*// Do some 'work'*` `sleep(1);` `*// Send reply back to client*` `zmq::message_t reply (5);` `memcpy (reply.data (), "World", 5);` `socket.send (reply);` }`` `**return** 0;}

hwserver.cpp: Hello World server

You can see that the ZeroMQ API is similar in C and C++. In a language like PHP or Java, we can hide even more and the code becomes even easier to read:

<?php*/**` `Hello World server\*` `Binds REP socket to tcp://\*:5555\*` `Expects "Hello" from client, replies with "World"\* @author Ian Barber <ian(dot)barber(at)gmail(dot)com>\*/*$context = **new** ZMQContext(1);*// Socket to talk to clients*$responder = **new** ZMQSocket($context, ZMQ::SOCKET_REP);$responder->bind("tcp://*:5555");**while** (**true**) {` `*// Wait for next request from client*` `$request = $responder->recv();` `printf ("Received request: [%s]**\n**", $request);` `*// Do some 'work'*` `sleep (1);` `*// Send reply back to client*` `$responder->send("World");}

hwserver.php: Hello World server

package guide;//// Hello World server in Java// Binds REP socket to tcp://*:5555// Expects "Hello" from client, replies with "World"//import org.zeromq.SocketType;import org.zeromq.ZMQ;import org.zeromq.ZContext;public class hwserver{public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception{try (ZContext context = new ZContext()) {// Socket to talk to clientsZMQ.Socket socket = context.createSocket(SocketType.REP);socket.bind("tcp://*:5555");while (!Thread.currentThread().isInterrupted()) {byte[] reply = socket.recv(0);System.out.println("Received " + ": [" + new String(reply, ZMQ.CHARSET) + "]");String response = "world";socket.send(response.getBytes(ZMQ.CHARSET), 0);Thread.sleep(1000); // Do some 'work'}}}}

hwserver.java: Hello World server

The server in other languages:

hwserver: Hello World server in C

C++ | C# | Clojure | CL | Delphi | Erlang | F# | Felix | Go | Haskell | Haxe | Java | Lua | Node.js | Objective-C| Perl | PHP | Python | Q | Racket | Ruby | Scala | Tcl | Ada | Basic | ooc

Here’s the client code:

hwclient: Hello World client in C

C++ | C# | Clojure | CL | Delphi | Erlang | F# | Felix | Go | Haskell | Haxe | Java | Lua | Node.js | Objective-C| Perl | PHP | Python | Q | Racket | Ruby | Scala | Tcl | Ada | Basic | ooc

这看起来太简单了,不太现实,但是正如我们已经知道的,ZeroMQ套接字具有超能力。您可以同时将数千个客户机扔到这个服务器上,它将继续愉快而快速地工作。有趣的是,先启动客户机,然后再启动服务器,看看它是如何工作的,然后再考虑一下这意味着什么。 让我们简要地解释一下这两个程序实际上在做什么。它们创建要使用的ZeroMQ context 和socket。不要担心这些词的意思。你会知道的。服务器将其REP (reply) socket 绑定到端口5555。服务器在一个循环中等待一个请求,每次都用一个响应来响应。客户机发送请求并从服务器读取响应。

如果您关闭服务器(Ctrl-C)并重新启动它,客户机将无法正常恢复。从进程崩溃中恢复并不那么容易。 创建一个可靠的request-reply流非常复杂,直到可靠的Request-Reply模式才会涉及它。

幕后发生了很多事情,但对我们程序员来说,重要的是代码有多短、多好,以及即使在重负载下也不会崩溃的频率。这是request-reply模式,可能是使用ZeroMQ的最简单方法。它映射到RPC和经典的 client/server模型。

需要对Strings小小的注意

除了以字节为单位的大小外,ZeroMQ对您发送的数据一无所知。这意味着您要负责安全地格式化它,以便应用程序能够读取它。为对象和复杂数据类型执行此操作是专门库(如协议缓冲区)的工作。但即使是字符串,你也要小心。

在C语言和其他一些语言中,字符串以空字节结束。我们可以发送一个字符串,如“HELLO”与额外的空字节:

zmq_send (requester, "Hello", 6, 0);

但是,如果您从另一种语言发送一个字符串,它可能不会包含那个空字节。例如,当我们用Python发送相同的字符串时,我们这样做:

socket.send ("Hello")

然后连接到线路上的是长度(对于较短的字符串是一个字节)和作为单个字符的字符串内容。

图 3 - ZeroMQ的 string

如果您从C程序中读取这段代码,您将得到一个看起来像字符串的东西,并且可能意外地表现得像字符串(如果幸运的话,这5个字节后面跟着一个无辜的潜伏的null),但是它不是一个正确的字符串。当您的客户机和服务器不同意字符串格式时,您将得到奇怪的结果。

当您在C语言中从ZeroMQ接收字符串数据时,您不能简单地相信它已经安全终止。每次读取字符串时,都应该为额外的字节分配一个带空间的新缓冲区,复制字符串,并使用null正确地终止它。

因此,让我们建立一个规则,即ZeroMQ字符串是指定长度的,并且在传输时不带null。在最简单的情况下(在我们的示例中我们将这样做),ZeroMQ字符串整洁地映射到ZeroMQ消息框架,它看起来像上面的图—长度和一些字节。

在C语言中,我们需要做的是接收一个ZeroMQ字符串并将其作为一个有效的C字符串发送给应用程序:

*//` `Receive ZeroMQ string from socket and convert into C string//` `Chops string at 255 chars, if it's longer***static** char *s_recv (void *socket) {` `char buffer [256];` `int size = zmq_recv (socket, buffer, 255, 0);` `**if** (size == -1)` `**return** NULL;` `**if** (size > 255)` `size = 255;` `buffer [size] = \0;` `*/\* use strndup(buffer, sizeof(buffer)-1) in \*nix **/` `**return** strdup (buffer);}

这是一个方便的helper函数,本着使我们可以有效重用的精神,让我们编写一个类似的s_send函数,它以正确的ZeroMQ格式发送字符串,并将其打包到一个可以重用的头文件中。

结果是zhelpers.h,它是一个相当长的源代码,而且只对C开发人员有乐趣,所以请在闲暇时阅读它。

版本报告

ZeroMQ有几个版本,通常,如果遇到问题,它会在以后的版本中得到修复。所以这是一个很有用的技巧,可以准确地知道您实际链接的是哪个版本的ZeroMQ。

这里有一个小程序可以做到这一点:

version: ZeroMQ version reporting in C

C++ | C# | Clojure | CL | Delphi | Erlang | F# | Felix | Go | Haskell | Java | Lua | Node.js | Objective-C | Perl| PHP | Python | Q | Ruby | Scala | Tcl | Ada | Basic | Haxe | ooc | Racket

传达信息

第二个经典模式是单向数据分发,其中服务器将更新推送到一组客户机。让我们看一个示例,它推出由邮政编码、温度和相对湿度组成的天气更新。我们将生成随机值,就像真实的气象站所做的那样。 这是服务器。我们将为这个应用程序使用端口5556:

wuserver: Weather update server in C

C++ | C# | Clojure | CL | Delphi | Erlang | F# | Felix | Go | Haskell | Haxe | Java | Lua | Node.js | Objective-C| Perl | PHP | Python | Racket | Ruby | Scala | Tcl | Ada | Basic | ooc | Q

这个更新流没有起点也没有终点,就像一个永无止境的广播。

下面是客户端应用程序,它监听更新流并获取与指定zip code有关的任何内容,默认情况下,纽约是开始任何冒险的好地方:

wuclient: Weather update client in C

C++ | C# | Clojure | CL | Delphi | Erlang | F# | Felix | Go | Haskell | Haxe | Java | Lua | Node.js | Objective-C| Perl | PHP | Python | Racket | Ruby | Scala | Tcl | Ada | Basic | ooc | Q

图 4 - Publish-Subscribe

注意,当您使用 SUB socket 时,必须使用zmq_setsockopt()和SUBSCRIBE设置订阅,如下面的代码所示。如果不设置任何订阅,就不会收到任何消息。这是初学者常犯的错误。订阅者可以设置许多订阅,这些订阅被添加到一起。也就是说,如果更新匹配任何订阅,订阅方将接收更新。订阅者还可以取消特定的订阅。订阅通常是,但不一定是可打印的字符串。请参阅zmq_setsockopt()了解其工作原理。

PUB-SUB socket 对(双方的意思)是异步的。客户机在循环中执行zmq_recv()(或者它只需要一次)。试图向 SUB socket发送消息将导致错误(单向的只能收不能发)。类似地,服务在需要的时候执行zmq_send(),但是不能在PUB scoket上执行zmq_recv()(单向的只能发不能收)。

理论上,对于ZeroMQ sockets,哪一端连接和哪一端绑定并不重要。然而,在实践中有一些未记录的差异,我将在稍后讨论。现在,绑定PUB并连接SUB,除非您的网络设计不允许这样做。

关于 PUB-SUB sockets,还有一件更重要的事情需要了解:您不知道订阅者何时开始接收消息。即使启动订阅服务器,等一下,然后启动发布服务器,订阅服务器也始终会错过发布服务器发送的第一个消息。这是因为当订阅服务器连接到发布服务器时(这需要一点时间,但不是零),发布服务器可能已经在发送消息了。

这种“慢速加入者”症状经常出现在很多人身上,我们将对此进行详细解释。 记住ZeroMQ执行异步I/O,即,在后台。假设有两个节点按如下顺序执行此操作:

- 订阅者连接到端点并接收和计数消息。

- 发布者绑定到端点并立即发送1,000条消息。

那么订阅者很可能不会收到任何东西。您会闪烁(困扰?),检查是否设置了正确的过滤器,然后重试一次,订阅者仍然不会收到任何内容。

建立TCP连接涉及到握手和握手,握手需要几毫秒,这取决于您的网络和对等点之间的跳数。在这段时间里,ZeroMQ可以发送许多消息。为了便于讨论,假设建立一个连接需要5毫秒,并且相同的链接每秒可以处理1M条消息。在订阅者连接到发布者的5毫秒期间,发布者只需要1毫秒就可以发送那些1K消息。

在Sockets and Patterns中,我们将解释如何同步发布者和订阅者,以便在订阅者真正连接并准备好之前不会开始发布数据。有一个简单而愚蠢的方法可以延迟发布,那就是sleep。但是,不要在实际应用程序中这样做,因为它非常脆弱、不优雅且速度很慢。使用sleep向您自己证明发生了什么,然后等待Sockets and Patterns来查看如何正确地执行此操作。

同步的另一种选择是简单地假设发布的数据流是无限的,没有开始和结束。还有一种假设是订阅者不关心在启动之前发生了什么。这是我们如何构建天气客户端示例的。

因此,客户端订阅其选择的zip code,并为该zip code收集100个更新。如果zip code是随机分布的,这意味着大约有一千万次来自服务器的更新。您可以启动客户机,然后启动服务器,客户机将继续工作。您可以随时停止和重启服务器,客户机将继续工作。当客户机收集了它的100个更新后,它计算平均值,打印并退出。

关于发布-订阅(发布-订阅) publish-subscribe (pub-sub) 模式的几点:

订阅服务器可以连接到多个发布服务器,每次使用一个连接调用。然后,数据将到达并交错(“公平排队”),这样就不会有一个发布者淹没其他发布者。

如果发布者没有连接的订阅者,那么它将删除所有消息。

如果您正在使用TCP,而订阅服务器很慢,则消息将在发布服务器上排队。稍后,我们将研究如何使用“高水位标记(high-water mark)”来保护publishers 不受此影响。

从ZeroMQ v3.x,当使用连接的协议(tcp://或ipc://)时,过滤发生在发布端。 使用epgm://协议,过滤发生在订阅方。在ZeroMQ v2.x,所有过滤都发生在订阅端。

我的笔记本电脑是2011年的英特尔i5,接收和过滤1000万条信息的时间是这样的:

$ time wuclientCollecting updates from weather server...Average temperature for zipcode '10001 ' was 28Freal 0m4.470suser 0m0.000ssys 0m0.008s

Divide and Conquer(分而治之)

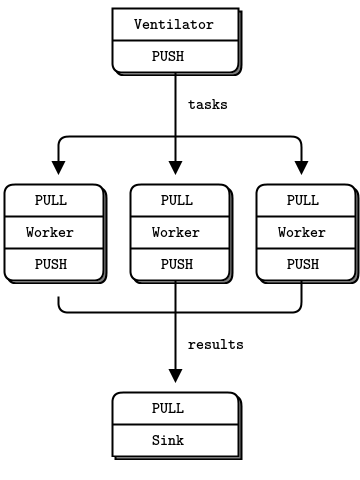

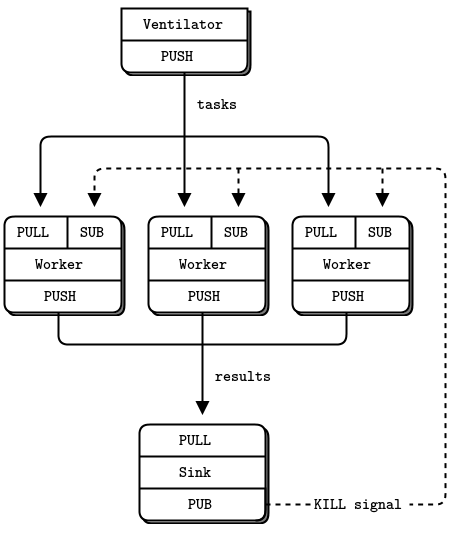

图 5 - Parallel Pipeline

作为最后一个例子(您肯定已经厌倦了有趣的代码,并希望重新研究比较抽象规范的语言学讨论),让我们来做一些超级计算。然后咖啡。我们的超级计算应用程序是一个相当典型的并行处理模型。我们有:

- 可同时完成多项任务的ventilator

- 一组处理任务的workers

- 从工作进程收集结果的sink

在现实中,workers 在超级快的机器上运行,可能使用gpu(图形处理单元)来做艰难的计算。这是ventilator 。它会生成100个任务,每个任务都有一条消息告诉worker睡眠几毫秒:

taskvent: Parallel task ventilator in C

C++ | C# | Clojure | CL | Delphi | Erlang | F# | Felix | Go | Haskell | Haxe | Java | Lua | Node.js | Objective-C| Perl | PHP | Python | Ruby | Scala | Tcl | Ada | Basic | ooc | Q | Racket

这是worker应用程序。它接收到一条消息,休眠几秒钟,然后发出信号,表示它已经完成: taskwork: Parallel task worker in C

C++ | C# | Clojure | CL | Delphi | Erlang | F# | Felix | Go | Haskell | Haxe | Java | Lua | Node.js | Objective-C| Perl | PHP | Python | Ruby | Scala | Tcl | Ada | Basic | ooc | Q | Racket

下面是sink应用程序。它收集了100个任务,然后计算出整个处理过程花费了多长时间,这样我们就可以确认,如果有多个任务,那么这些工人确实是并行运行的: tasksink: Parallel task sink in C

C++ | C# | Clojure | CL | Delphi | Erlang | F# | Felix | Go | Haskell | Haxe | Java | Lua | Node.js | Objective-C| Perl | PHP | Python | Ruby | Scala | Tcl | Ada | Basic | ooc | Q | Racket

- 1 worker: total elapsed time: 5034 msecs.

- 2 workers: total elapsed time: 2421 msecs.

- 4 workers: total elapsed time: 1018 msecs.

让我们更详细地看看这段代码的一些方面:

worker将上游连接到ventilator ,下游连接到sink。这意味着可以任意添加worker。如果worker绑定到他们的端点,您将需要(a)更多的端点和(b)每次添加worker时修改ventilator 和/或sink。我们说ventilator 和sink是我们建筑的“稳定”部分,worker是建筑的“动态”部分。

我们必须在所有worker正在启动和运行后开始批处理(We have to synchronize the start of the batch with all workers being up and running.)。这是ZeroMQ中一个相当常见的问题,没有简单的解决方案。’ zmq_connect ‘方法需要一定的时间。因此,当一组worker连接到ventilator 时,第一个成功连接的worker将在短时间内获得大量信息,而其他worker也在连接。如果不以某种方式同步批处理的开始,系统就根本不会并行运行。试着把ventilator 里的等待时间去掉,看看会发生什么。

ventilator 的PUSH socket 将任务分配给worker(假设他们在批处理开始输出之前都连接好了)。这就是所谓的“负载平衡”,我们将再次详细讨论它。

sink的PULL均匀地收集worker的结果。这叫做“公平排队”。 图 6 - Fair Queuing

管道模式(pipeline pattern)还表现出“慢连接者”综合征,导致指责PUSH sockets不能正确地平衡负载。如果您正在使用 PUSH 和 PULL,而您的一个worker获得的消息比其他worker多得多,这是因为这个PULL socket连接得比其他worker更快,并且在其他worker设法连接之前捕获了大量消息。如果您想要适当的负载平衡,您可能需要查看Advanced Request-Reply Patterns中的负载平衡模式。

ZeroMQ编程

看过一些例子之后,您一定很想开始在一些应用程序中使用ZeroMQ。在你开始之前,深呼吸,放松,并思考一些基本的建议,这会帮你减轻很多压力和困惑。

循序渐进的学习ZeroMQ。它只是一个简单的API,但它隐藏了大量的可能性。慢慢地把握每一种可能性。

写好代码。丑陋的代码隐藏了问题,让别人很难帮助你。您可能已经习惯了无意义的变量名,但是阅读您代码的人不会习惯。使用真实的单词,而不是“我太粗心了,不能告诉您这个变量的真正用途”。使用一致的缩进和干净的布局。写好代码,你的世界就会更舒适。

一边做一边测试。当您的程序无法工作时,您应该知道应该归咎于哪五行。当你使用极具魅力的ZeroMQ的时候,这一点尤其正确,因为在你开始尝试的几次之后,它都不会起作用。

- 当您发现有些东西不像预期的那样工作时,将您的代码分成几部分,测试每一部分,看看哪一部分不工作。ZeroMQ允许你编写模块化代码;利用这一点。

根据需要进行抽象(类、方法等)。如果你复制/粘贴了很多代码,你也会复制/粘贴错误。

正确理解 Context

ZeroMQ应用程序总是从创建Context开始,然后使用Context创建sockets。在C语言中,它是zmq_ctx_new()调用。您应该在流程中创建并使用一个Context。从技术上讲,Context是一个进程中所有sockets的容器,它充当inproc sockets的传输,inproc sockets是在一个进程中连接线程的最快方式。如果在运行时一个流程有两个Context,那么它们就像独立的ZeroMQ实例。如果这是你明确想要的,好的,否则记住:

Call zmq_ctx_new() once at the start of a process, and zmq_ctx_destroy() once at the end.

在流程开始时调用zmq_ctx_new()一次,在流程结束时调用zmq_ctx_destroy()一次。 如果使用fork()系统调用,那么在fork之后和子进程代码的开头执行zmq_ctx_new()。通常,您希望在子进程中执行有趣的(ZeroMQ)操作,而在父进程中执行乏味的流程管理。

退出前清理

一流的程序员与一流的杀手有相同的座右铭:当你完成工作时,总是要清理干净。当您在Python之类的语言中使用ZeroMQ时,会自动释放一些内容。但是在使用C语言时,必须小心地释放对象,否则会导致内存泄漏、应用程序不稳定,通常还会产生坏的因果报应。

内存泄漏是一回事,但是ZeroMQ对如何退出应用程序非常挑剔。原因是技术性的和痛苦的,但是结果是,如果您打开任何sockets ,zmq_ctx_destroy()函数将永远挂起。即使关闭所有sockets ,默认情况下,如果有挂起连接或发送,zmq_ctx_destroy()将永远等待,除非在关闭这些sockets 之前将这些sockets 的逗留时间设置为零。

我们需要担心的ZeroMQ对象是 messages, sockets, 和 contexts。幸运的是,它非常简单,至少在简单的程序中:

可以时使用zmq_send()和zmq_recv(),因为它避免了使用zmq_msg_t对象。

如果您确实使用zmq_msg_recv(),那么总是在使用完接收到的消息后立即释放它,方法是调用zmq_msg_close()。

如果您打开和关闭了许多sockets,这可能是您需要重新设计应用程序的标志。在某些情况下,在销毁上下文之前不会释放sockets句柄。

退出程序后,关闭socket,然后调用zmq_ctx_destroy()。这会销毁context。

这至少是C开发的情况。在具有自动对象销毁的语言中,离开作用域时将销毁套接字和上下文。 如果使用异常,则必须在类似“final”块的地方进行清理,这与任何资源都是一样的。

如果你在做多线程的工作,它会变得比这更复杂。我们将在下一章中讨论多线程,但是由于有些人会不顾警告,在安全地行走前先尝试运行,下面是在多线程ZeroMQ应用程序中实现干净退出的快速而又脏的指南。

首先,不要尝试从多个线程使用同一个socket。请不要解释为什么你认为这将是非常有趣的,只是请不要这样做。接下来,您需要关闭具有正在进行的请求的每个socket。正确的方法是设置一个较低的逗留值(1秒),然后关闭socket。如果您的语言绑定在销毁context时没有自动为您完成此任务,我建议发送一个补丁。

最后,销毁context。这将导致任何阻塞接收或轮询或发送附加线程(即,共享context)返回一个错误。捕获该错误,然后设置逗留,关闭该线程中的socket,然后退出。不要两次破坏相同的Context。主线程中的zmq_ctx_destroy将阻塞,直到它所知道的所有socket都安全关闭为止。

瞧!这是非常复杂和痛苦的,任何称职的语言绑定作者都会自动地这样做,使socket关闭舞蹈变得不必要。

为什么我们需要ZeroMQ

既然您已经看到了ZeroMQ的作用,让我们回到“为什么”。

现在的许多应用程序都是由跨越某种网络(LAN或Internet)的组件组成的。因此,许多应用程序开发人员最终都会进行某种消息传递。一些开发人员使用消息队列产品,但大多数时候他们自己使用TCP或UDP来完成。这些协议并不难使用,但是从a向B发送几个字节与以任何一种可靠的方式进行消息传递之间有很大的区别。

让我们看看在开始使用原始TCP连接各个部分时所面临的典型问题。任何可重用的消息层都需要解决所有或大部分问题:

- 我们如何处理I/O?我们的应用程序是阻塞还是在后台处理I/O ?这是一个关键的设计决策。阻塞I/O会创建伸缩性不好的体系结构。但是后台I/O很难正确地执行。

- 我们如何处理动态组件,即,暂时消失的碎片?我们是否将组件正式划分为“客户端”和“服务器”,并要求服务器不能消失?如果我们想把服务器连接到服务器呢?我们是否每隔几秒钟就尝试重新连接?

- 我们如何在网络上表示消息?我们如何设置数据的框架,使其易于读写,不受缓冲区溢出的影响,对小消息有效,但对于那些戴着派对帽子跳舞的猫的大型视频来说,这已经足够了吗?

- 我们如何处理无法立即交付的消息?特别是,如果我们正在等待一个组件重新联机?我们是丢弃消息,将它们放入数据库,还是放入内存队列?

- 我们在哪里存储消息队列?如果从队列读取的组件非常慢,导致我们的队列增加,会发生什么?那么我们的策略是什么呢?

- 我们如何处理丢失的消息?我们是等待新数据、请求重发,还是构建某种确保消息不会丢失的可靠性层?如果这个层本身崩溃了呢?

- 如果我们需要使用不同的网络传输怎么办?比如说,多播而不是TCP单播?还是IPv6 ?我们是否需要重写应用程序,还是在某个层中抽象传输?

- 我们如何路由消息?我们可以向多个对等点发送相同的消息吗?我们可以将回复发送回原始请求者吗?

- 我们如何为另一种语言编写API ?我们是重新实现一个线级协议,还是重新打包一个库?如果是前者,如何保证栈的高效稳定?如果是后者,我们如何保证互操作性?

- 我们如何表示数据,以便在不同的体系结构之间读取数据?我们是否对数据类型强制执行特定的编码?这是消息传递系统的工作,而不是更高一层的工作。

- 我们如何处理网络错误?我们是等待并重试,默不作声地忽略它们,还是中止?

以一个典型的开源项目为例,比如Hadoop Zookeeper,在src/ C /src/ Zookeeper . C中读取C API代码。当我在2013年1月读到这段代码时,它是4200行神秘代码,其中有一个未文档化的客户机/服务器网络通信协议。我认为这是有效的,因为它使用轮询而不是选择。但实际上,Zookeeper应该使用通用消息层和显式文档化的有线级协议。对于团队来说,一遍又一遍地构建这个特定的轮子是非常浪费的。

但是如何创建可重用的消息层呢?为什么在如此多的项目需要这种技术的时候,人们仍然在用一种很困难的方式来完成它,在他们的代码中驱动TCP套接字,并一次又一次地解决长列表中的问题?

事实证明,构建可重用的消息传递系统是非常困难的,这就是为什么很少有自由/开源软件项目尝试过,以及为什么商业消息传递产品是复杂的、昂贵的、不灵活的和脆弱的。2006年,iMatix设计了AMQP,它开始为自由/开源软件开发人员提供消息系统的第一个可重用配方。AMQP比其他许多设计都要好,但仍然相对复杂、昂贵和脆弱。学习使用它需要几周的时间,而创建当事情变得棘手时不会崩溃的稳定的体系结构需要几个月的时间。

图 7 - Messaging as it Starts

大多数消息传递项目,如AMQP,都试图通过发明一个新的概念“broker”来解决这一长串问题,该概念负责寻址、路由和排队,从而以可重用的方式解决这些问题。这将导致客户机/服务器协议或一些未文档化协议之上的一组api,这些协议允许应用程序与此broker通信。在减少大型网络的复杂性方面,Brokers 是一件很好的事情。但是在Zookeeper这样的产品中添加基于代理的消息会让情况变得更糟,而不是更好。这将意味着添加一个额外的大框和一个新的单点故障。broker 迅速成为一个瓶颈和一个需要管理的新风险。如果软件支持它,我们可以添加第二个、第三个和第四个broker ,并制定一些故障转移方案。人们这样做。它创造了更多的活动部件,更多的复杂性,以及更多需要打破的东西。

以broker 为中心需要自己的operations team。你确实需要日日夜夜地观察这些brokers,当他们开始行为不端时,你要用棍子打他们。你需要盒子,你需要备份盒子,你需要人们来管理这些盒子。它只值得为大型应用程序做很多移动的部分,由几个团队的人在几年的时间内构建。

图 8 - Messaging as it Becomes

因此,中小型应用程序开发人员陷入了困境。它们要么避免网络编程,要么开发不可伸缩的单片应用程序。或者他们跳入网络编程,使脆弱、复杂的应用程序难以维护。或者他们押注于一个消息传递产品,最终开发出可伸缩的应用程序,这些应用程序依赖于昂贵且容易崩溃的技术。一直没有真正好的选择,这也许就是为什么messaging 在很大程度上停留在上个世纪,并激起强烈的情感:对用户来说是负面的,对那些销售支持和许可的人来说是欢欣鼓舞的。

我们需要的是能够完成消息传递功能的东西,但它的实现方式非常简单和廉价,可以在任何应用程序中运行,成本几乎为零。它应该是一个链接的库,没有任何其他依赖关系。没有额外的移动部件,所以没有额外的风险。它应该运行在任何操作系统上,并且可以使用任何编程语言。

这就是ZeroMQ:一个高效的、可嵌入的库,它解决了应用程序需要在不花费太多成本的情况下在网络上保持良好弹性的大部分问题。

特别地:

它在后台线程中异步处理I/O。这些线程使用无锁数据结构与应用程序线程通信,因此并发ZeroMQ应用程序不需要锁、信号量或其他等待状态。

组件可以动态进出,ZeroMQ将自动重新连接。这意味着您可以以任何顺序启动组件。您可以创建“面向服务的体系结构”(service-oriented architecture, soa),其中服务可以随时加入和离开网络。

它在需要时自动对消息进行排队。它很聪明地做到了这一点,在对消息进行排队之前,尽可能地将消息推送到接收端。

它有办法处理过满的队列(称为“高水位”)。当队列已满时,ZeroMQ会根据您正在执行的消息类型(所谓的“模式”)自动阻塞发送者或丢弃消息。

它允许您的应用程序通过任意传输相互通信:TCP、多播、进程内、进程间。您不需要更改代码来使用不同的传输。

它使用依赖于消息传递模式的不同策略安全地处理慢速/阻塞的readers 。

它允许您使用各种模式路由消息,比如请求-应答和发布-订阅。这些模式是取决于你如何创建拓扑结构的,即网络的结构。

它允许您创建代理来通过一个调用对消息进行排队、转发或捕获。代理可以降低网络的互连复杂性。

它通过在网络上使用一个简单的框架,完全按照发送的方式传递整个消息。如果您写了一条10k的消息,您将收到一条10k的消息。

它不将任何格式强加于消息。它们是从0到gb大小的水滴。当您想要表示数据时,您可以在顶部选择一些其他产品,例如msgpack、谷歌的协议缓冲区等。

它通过在有意义的情况下自动重试来智能地处理网络错误。

它可以减少你的碳足迹。用更少的CPU做更多的事情意味着您的机器使用更少的能量,并且您可以让旧的机器使用更长时间。 Al Gore会喜欢ZeroMQ的。

- 实际上ZeroMQ做的远不止这些。 它对如何开发支持网络的应用程序具有颠覆性的影响。从表面上看,它是一个受套接字启发的API,您可以在其上执行’ zmq_recv() ‘和’ zmq_send() ‘。但是消息处理很快成为中心循环,您的应用程序很快就分解为一组消息处理任务。它优雅自然。它是可伸缩的:每个任务都映射到一个节点,节点之间通过任意传输进行通信。一个进程中的两个节点(节点是一个线程)、一个框中的两个节点(节点是一个进程)或一个网络上的两个节点(节点是一个框)—都是一样的,没有应用程序代码更改。

(可伸缩性的scoket)

Socket Scalability(可伸缩性的scoket)

让我们看看ZeroMQ的可伸缩性。下面是一个shell脚本,它先启动天气服务器,然后并行地启动一堆客户机:

wuserver &wuclient 12345 &wuclient 23456 &wuclient 34567 &wuclient 45678 &wuclient 56789 &

As the clients run, we take a look at the active processes using the top command’, and we see something like (on a 4-core box):

PID USER PR NI VIRT RES SHR S %CPU %MEM TIME+ COMMAND7136 ph 20 0 1040m 959m 1156 R 157 12.0 16:25.47 wuserver7966 ph 20 0 98608 1804 1372 S 33 0.0 0:03.94 wuclient7963 ph 20 0 33116 1748 1372 S 14 0.0 0:00.76 wuclient7965 ph 20 0 33116 1784 1372 S 6 0.0 0:00.47 wuclient7964 ph 20 0 33116 1788 1372 S 5 0.0 0:00.25 wuclient7967 ph 20 0 33072 1740 1372 S 5 0.0 0:00.35 wuclient

让我们想一下这里发生了什么。气象服务器只有一个套接字,但是这里我们让它并行地向五个客户机发送数据。我们可以有成千上万的并发客户端。服务器应用程序不会看到它们,也不会直接与它们对话。所以ZeroMQ套接字就像一台小服务器,默默地接受客户机请求,并以网络最快的速度将数据发送给它们。它是一个多线程服务器,可以从CPU中挤出更多的能量。

从ZeroMQ v2.2升级到ZeroMQ v3.2

Compatible Changes(兼容变更)

这些更改不会直接影响现有的应用程序代码:

Pub-sub filtering现在运行在在publisher而不是在subscriber,这在许多pub-sub 用例中显著提高了性能 You can mix v3.2 and v2.1/v2.2 publishers and subscribers safely.

ZeroMQ v3.2 has many new API methods (

zmq_disconnect(),zmq_unbind(),zmq_monitor(),zmq_ctx_set(), etc.)

不兼容的变更

这些是影响应用程序和语言绑定的主要领域:(These are the main areas of impact on applications and language bindings):

Changed send/recv methods:

zmq_send()andzmq_recv()have a different, simpler interface, and the old functionality is now provided byzmq_msg_send()andzmq_msg_recv(). Symptom: compile errors. Solution: fix up your code.这两种方法成功时返回正值,错误时返回-1。在v2。他们成功时总是零回报。症状:工作正常时明显的错误。解决方案:严格测试返回代码= -1,而不是非零.

zmq_poll()现在等待毫秒,而不是微秒。症状:应用程序停止响应(实际上响应慢了1000倍)。解决方案::在所有zmq_poll调用中,使用下面定义的ZMQ_POLL_MSEC宏。“ZMQ_NOBLOCK”现在称为“ZMQ_DONTWAIT”。症状:在“ZMQ NOBLOCK”宏上编译失败。

“ZMQ_HWM”socket 选项现在分为“ZMQ_SNDHWM”和“ZMQ_RCVHWM”。症状:在’ ZMQ_HWM ‘宏上编译失败。

大多数但不是所有的’ zmq_getsockopt() ‘选项现在都是整数值。症状:运行时错误返回’ zmq_setsockopt ‘和’ zmq_getsockopt ‘。

‘ ZMQ_SWAP ‘选项已被删除。症状:在’ ZMQ_SWAP ‘上编译失败。解决方案:重新设计使用此功能的任何代码。

Suggested Shim Macros

对于希望在两个v2上运行的应用程序。x和v3.2,例如语言绑定,我们的建议是尽可能地模拟v3.2。这里有一些C宏定义,可以帮助您的C/ c++代码跨两个版本工作(取自CZMQ):

\#ifndef ZMQ_DONTWAIT\#` `define ZMQ_DONTWAIT` `ZMQ_NOBLOCK\#endif\#if ZMQ_VERSION_MAJOR == 2\#` `define zmq_msg_send(msg,sock,opt) zmq_send (sock, msg, opt)\#` `define zmq_msg_recv(msg,sock,opt) zmq_recv (sock, msg, opt)\#` `define zmq_ctx_destroy(context) zmq_term(context)\#` `define ZMQ_POLL_MSEC` `1000` `*// zmq_poll is usec*\#` `define ZMQ_SNDHWM ZMQ_HWM\#` `define ZMQ_RCVHWM ZMQ_HWM\#elif ZMQ_VERSION_MAJOR == 3\#` `define ZMQ_POLL_MSEC` `1` `*// zmq_poll is msec*\#endif

Warning: 不稳定的范例!

传统的网络编程建立在一个socket 与一个connection、一个peer通信的一般假设之上。有多播协议,但这些都是外来的。当我们假设“”one socket = one connection””时,我们以某种方式扩展架构。我们创建逻辑线程,其中每个线程使用一个socket和一个peer。我们在这些线程中放置intelligence 和状态。 在ZeroMQ领域,sockets是快速后台通信引擎的入口,这些引擎可以自动地为您管理一整套连接。您无法查看、处理、打开、关闭或将状态附加到这些连接。无论您使用阻塞发送、接收或轮询,您只能与socket通信,而不是它为您管理的连接。连接是私有的,不可见的,这是ZeroMQ可伸缩性的关键。 这是因为,与socket通信的代码可以处理任意数量的连接,而无需更改周围的任何网络协议。ZeroMQ中的消息传递模式比应用程序代码中的消息传递模式扩展得更便宜。

所以一般的假设不再适用。当您阅读代码示例时,您的大脑将尝试将它们映射到您所知道的内容。您将读取“socket”并认为“啊,这表示到另一个节点的连接”。这是错误的。当你读到“thread”时,你的大脑又会想,“啊,一个thread代表了与另一个节点的连接”,你的大脑又会出错。 如果你是第一次读这本指南的话,要意识到这一点,直到你在一两天内编写ZeroMQ代码(可能是三到四天),你可能会感到困惑,特别是ZeroMQ使事情多么简单,你可以试着把这个普遍的假设强加给ZeroMQ,它不会工作。然后你将经历你的启蒙和信任的时刻,当一切都变得清晰的时候,你将经历“zap-pow-kaboom satori”的时刻。

Chapter 2 - Sockets and Patterns

在第1章—基础知识中,我们将ZeroMQ作为驱动器,并提供了一些主要ZeroMQ模式的基本示例:请求-应答、发布-订阅和管道。在本章中,我们将亲自动手,开始学习如何在实际程序中使用这些工具。

我们将讨论:

- 如何创建和使用ZeroMQ Sockets。

- 如何在Sockets上发送和接收消息。 如何围绕ZeroMQ的异步I/O模型构建应用程序。 如何在一个线程中处理多个Sockets。 如何正确处理致命和非致命错误。 如何处理像Ctrl-C这样的中断信号。 如何干净地关闭ZeroMQ应用程序。 如何检查ZeroMQ应用程序的内存泄漏。 如何发送和接收多部分消息。 如何跨网络转发消息。 如何构建一个简单的消息队列代理(broker)。 如何使用ZeroMQ编写多线程应用程序。 如何使用ZeroMQ在线程之间发送信号。 如何使用ZeroMQ来协调节点网络。 如何为发布-订阅创建和使用消息信封。 使用HWM (high-water mark)来防止内存溢出。

The Socket API

说句老实话,ZeroMQ对你耍了个花招,对此我们不道歉。这是为了你好,我们比你更伤心。ZeroMQ提供了一个熟悉的基于Socket的API,要隐藏一堆消息处理引擎需要付出很大的努力。然而,结果将慢慢地修正您关于如何设计和编写分布式软件的世界观。

Socket实际上是网络编程的标准API, as well as being useful for stopping your eyes from falling onto your cheeks(怎么翻译? 大跌眼镜?)。ZeroMQ对开发人员特别有吸引力的一点是,它使用Socket和messages ,而不是其他任意一组概念。感谢Martin Sustrik的成功。它将“面向消息的中间件”变成了“额外辛辣(Extra Spicy ,升级版)的Sockets!”这让我们对披萨产生了一种奇怪的渴望,并渴望了解更多。 就像最喜欢的菜一样,ZeroMQsockets 很容易消化。sockets 的生命由四个部分组成,就像BSDsockets 一样:

创造和摧毁sockets ,它们一起形成一个插座生命的业力循环(see

zmq_socket(),zmq_close()).通过设置套接字上的选项并在必要时检查它们来配置套接字(see

zmq_setsockopt(),zmq_getsockopt()).Plugging sockets into the network topology by creating ZeroMQ connections to and from them (see

zmq_bind(),zmq_connect()).通过创建与它们之间的ZeroMQ连接,将sockets插入网络拓扑(see

zmq_msg_send(),zmq_msg_recv()).

注意,套接字总是空指针,消息(我们很快就会讲到)是结构。所以在C语言中,按原样传递sockets ,但是在所有处理消息的函数中传递消息的地址,比如zmq_msg_send()和zmq_msg_recv()。作为一个助记符,请认识到“在ZeroMQ中,您所有的sockets 都属于我们”,但是消息实际上是您在代码中拥有的东西。 创建、销毁和配置Sockets的工作原理与您对任何对象的期望一样。但是请记住ZeroMQ是一个异步的、有弹性的结构。这对我们如何将Sockets插入网络拓扑以及之后如何使用Sockets有一定的影响。

将Sockets插入拓扑中

要在两个节点之间创建连接,可以在一个节点中使用zmq_bind(),在另一个节点中使用zmq_connect()。一般来说,执行zmq_bind()的节点是一个“服务器”,位于一个已知的网络地址上,执行zmq_connect()的节点是一个“客户机”,具有未知或任意的网络地址。因此,我们说“将socket 绑定到端点”和“将socket 连接到端点”,端点就是那个已知的网络地址。

ZeroMQ连接与传统TCP连接有些不同。主要的显著差异是:

They go across an arbitrary transport (

inproc,ipc,tcp,pgm, orepgm). Seezmq_inproc(),zmq_ipc(),zmq_tcp(),zmq_pgm(), andzmq_epgm().一个将socket可能有许多传出和传入连接。.

没有’ zmq_accept ‘()方法。当socket绑定到端点时,它将自动开始接受连接

网络连接本身发生在后台,如果网络连接中断,ZeroMQ将自动重新连接(例如,如果peer 消失,然后返回)。

您的应用程序代码不能直接使用这些连接;它们被封装在socket下面。

许多架构遵循某种客户机/服务器模型,其中服务器是最静态的组件,而客户机是最动态的组件,即,他们来了又走的最多。有时存在寻址问题:服务器对客户机可见,但是反过来不一定是这样的。因此,很明显,哪个节点应该执行zmq_bind()(服务器),而哪个节点应该执行zmq_connect()(客户机)。它还取决于您使用的socket的类型,对于不常见的网络体系结构有一些例外。稍后我们将研究socket类型。

现在,假设在启动服务器之前先启动客户机。在传统的网络中,我们会看到一个大大的红色失败标志。但是ZeroMQ让我们任意地开始和停止。只要客户机节点执行zmq_connect(),连接就存在,该节点就可以开始向socket写入消息。在某个阶段(希望是在消息排队太多而开始被丢弃或客户机阻塞之前),服务器会启动,执行zmq_bind(),然后ZeroMQ开始传递消息。 一个服务器节点可以绑定到许多端点(即协议和地址的组合),并且它可以使用一个socket来实现这一点。这意味着它将接受跨不同传输的连接:

zmq_bind (socket, "tcp://*:5555");zmq_bind (socket, "tcp://*:9999");zmq_bind (socket, "inproc://somename");

对于大多数传输,不能像UDP那样两次绑定到同一个端点。然而,ipc传输允许一个进程绑定到第一个进程已经使用的端点。这意味着允许进程在崩溃后恢复。 虽然ZeroMQ试图对哪边绑定和哪边连接保持中立,但还是有区别的。稍后我们将更详细地看到这些。其结果是,您通常应该将“服务器”视为拓扑的静态部分,它绑定到或多或少固定的端点,而将“客户机”视为动态部分,它们来来去去并连接到这些端点。然后,围绕这个模型设计应用程序。它“正常工作”的可能性要大得多。

Sockets 有多个类型。Socket类型定义Sockets的语义、Socket向内和向外路由消息的策略、队列等。您可以将某些类型的Socket连接在一起,例如,publisher Socket和subscriber Socket。Socket在“messaging patterns”中协同工作。稍后我们将更详细地讨论这个问题。 正是能够以这些不同的方式连接Sockets,使ZeroMQ具备了作为消息队列系统的基本功能。在此之上还有一些层,比如代理,我们稍后将讨论它。但从本质上讲,使用ZeroMQ,您可以像孩子的积木玩具一样将各个部分拼接在一起,从而定义您的网络体系结构。

发送和接收消息

要发送和接收消息,可以使用zmq_msg_send()和zmq_msg_recv()方法。这些名称都是传统的,但是ZeroMQ的I/O模型与传统的TCP模型有很大的不同,您需要时间来理解它。

图 9 - TCP sockets are 1 to 1

让我们来看看TCP sockets和ZeroMQ sockets在处理数据方面的主要区别:

- ZeroMQ套接字像UDP一样携带消息,而不像TCP那样携带字节流。ZeroMQ消息是长度指定的二进制数据。我们很快就会讲到信息;它们的设计是针对性能进行优化的,因此有点棘手。

- ZeroMQ套接字在后台线程中执行I/O。这意味着消息到达本地输入队列并从本地输出队列发送,无论您的应用程序在忙什么。

- 根据socket类型,ZeroMQ sockets具有内置的1对n路由行为。

zmq_send()方法实际上并不将消息发送到socket connection(s)。它对消息进行排队,以便I/O线程可以异步发送消息。它不会阻塞,除非在某些异常情况下。因此,当zmq_send()返回到应用程序时,不一定要发送消息。

单播传输(Unicast Transports)

ZeroMQ提供了一组单播传输(inproc、ipc和tcp)和多播传输(epgm、pgm)。多播是一种先进的技术,我们稍后会讲到。不要开始使用它,除非你知道你的扇出比将使1到n单播不可能(Don’t even start using it unless you know that your fan-out ratios will make 1-to-N unicast impossible.)。

对于大多数常见的情况,使用tcp,这是一个断开连接式(disconnected )的tcp传输。它是弹性的,便携式的,和足够快的大多数情况下。我们将此称为断开连接式(disconnected ),因为ZeroMQ的tcp传输不需要在连接到端点之前存在端点。客户机和服务器可以随时连接和绑定,可以来回切换,并且对应用程序保持透明。

进程间ipc传输也是断开连接式(disconnected )的,就像tcp一样。它有一个限制:它还不能在Windows上运行。按照惯例,我们使用带有“.ipc”扩展名,以避免与其他文件名的潜在冲突。在UNIX系统上,如果使用ipc端点,则需要使用适当的权限创建这些端点,否则在不同用户id下运行的进程之间可能无法共享这些端点。您还必须确保所有进程都可以访问这些文件,例如,在相同的工作目录中运行。

线程间传输(inproc)是一种连接(connected )的信号传输。它比tcp或ipc快得多。与tcp和ipc相比,这种传输有一个特定的限制:服务器必须在任何客户机发出连接之前发出绑定。这是ZeroMQ的未来版本可能会解决的问题,但目前这定义了如何使用inproc套接字。我们创建并绑定一个socket,并启动子线程,子线程创建并连接其他socket。

ZeroMQ 不是中立的载体(Neutral Carrier)

ZeroMQ新手常问的一个问题(我自己也问过这个问题)是:“如何用ZeroMQ编写XYZ服务器?” 例如,“如何用ZeroMQ编写HTTP服务器?”这意味着,如果我们使用普通sockets 来承载HTTP请求和响应,我们应该能够使用ZeroMQsockets 来做同样的事情,只是更快更好。

答案曾经是“事情不是这样的”。ZeroMQ并不是一个中立的载体:它在使用的传输协议上强加了一个框架。这种帧与现有协议不兼容,现有协议倾向于使用自己的帧。例如,比较TCP/IP上的HTTP请求和ZeroMQ请求。

图 10 - HTTP on the Wire

HTTP请求使用CR-LF作为最简单的帧分隔符,而ZeroMQ使用指定长度的帧。因此,您可以使用ZeroMQ编写类似http的协议,例如使用request-reply socket模式。但它不是HTTP。

图 11 - ZeroMQ on the Wire

但是,从v3.3开始,ZeroMQ就有一个名为ZMQ_ROUTER_RAW的套接字选项,允许您在不使用ZeroMQ帧的情况下读写数据。您可以使用它来读写正确的HTTP请求和响应。Hardeep Singh对此做出了贡献,这样他就可以从ZeroMQ应用程序连接到Telnet服务器。在编写本文时,这还处于试验阶段,但它显示了ZeroMQ如何不断发展以解决新问题。也许下一个补丁就是你的了。

I/O Threads

我们说过ZeroMQ在后台线程中执行I/O。一个I/O线程(适用于所有类型socket)对于除最极端的应用程序之外的所有应用程序都是足够的。当您创建一个新的context时,它从一个I/O线程开始。一般的经验法则是,每秒允许1千兆字节(gigabyte ,1GB?)的数据进出一个I/O线程。要增加I/O线程的数量,请在创建任何socket之前使用zmq_ctx_set()调用:

int io_threads = 4;void *context = zmq_ctx_new ();zmq_ctx_set (context, ZMQ_IO_THREADS, io_threads);assert (zmq_ctx_get (context, ZMQ_IO_THREADS) == io_threads);

我们已经看到一个socket可以同时处理几十个、甚至数千个连接。这对如何编写应用程序具有根本性的影响。传统的网络应用程序每个远程连接有一个进程或一个线程,该进程或线程处理一个scoket。ZeroMQ允许您将整个结构折叠成一个进程,然后根据需要将其拆分以实现可伸缩性

如果您只将ZeroMQ用于线程间通信(即,一个没有外部scoket I/O的多线程应用程序)您可以将I/O线程设置为零。这不是一个重要的优化,更多的是一个好奇心。

消息传递模式(Messaging Patterns)

在ZeroMQ socket API的牛皮纸包装下,隐藏着消息传递模式的世界。如果您有企业消息传递方面的背景知识,或者熟悉UDP,那么您对这些可能会有些熟悉。但对ZeroMQ的大多数新来者来说,它们是一个惊喜。我们非常习惯TCP范例,其中socket 一对一地映射到另一个节点。

让我们简要回顾一下ZeroMQ为您做了什么。它将数据块(消息)快速有效地交付给节点。您可以将节点映射到线程、进程或节点。ZeroMQ为您的应用程序提供了一个可以使用的socket API,而不管实际的传输是什么(比如进程内、进程间、TCP或多播)。它会在同行来来去去时自动重新连接到他们。它根据需要在发送方和接收方对消息进行排队。它限制这些队列,以防止进程耗尽内存。它处理socket 错误。它在后台线程中执行所有I/O操作。它使用无锁技术在节点之间进行通信,因此从不存在锁、等待、信号量或死锁。

但是,它会根据称为模式的精确配方路由和排队消息。正是这些模式提供了ZeroMQ的智能。它们浓缩了我们来之不易的经验,即最好的数据和工作分发方式。ZeroMQ的模式是硬编码的,但是未来的版本可能允许用户定义模式。

ZeroMQ模式由具有匹配类型的 sockets 对实现。换句话说,要理解ZeroMQ模式,您需要了解sockets 类型及其协同工作的方式。大多数情况下,这只需要学习;在这个层面上,没有什么是显而易见的。 内置的核心ZeroMQ模式是:

Request-reply: 它将一组客户机连接到一组服务。这是一个远程过程调用和任务分发模式。

Pub-sub:它将一组发布者连接到一组订阅者。这是一个数据发布模式。

Pipeline:它以扇出/扇入模式连接节点,该模式可以有多个步骤和循环。 这是一个并行的任务分发和收集模式

Exclusive pair:只连接两个sockets 。这是一个用于连接进程中的两个线程的模式,不要与“普通”sockets 对混淆。 我们在第1章-基础知识中讨论了前三种模式,我们将在本章后面看到the exclusive pair 模式。zmq_socket()手册页对模式非常清楚——值得反复阅读几遍,直到开始理解为止。这些socket组合对连接绑定对是有效的(任何一方都可以绑定):

- PUB and SUB

- REQ and REP

- REQ and ROUTER (注意,REQ插入了一个额外的空帧)

- DEALER and REP (注意,REP插入了一个额外的空帧)

- DEALER and ROUTER

- DEALER and DEALER

- ROUTER and ROUTER

- PUSH and PULL

- PAIR and PAIR

您还将看到对XPUB和XSUB sockets的引用,我们稍后将对此进行讨论(它们类似于PUB和SUB的原始版本)。任何其他组合都将产生未文档化和不可靠的结果,如果您尝试ZeroMQ的未来版本,可能会返回错误。当然,您可以并且将通过代码桥接其他socket类型,即,从一个socket类型读取并写入到另一个socket类型。

High-Level Messaging Patterns

这四个核心模式被煮成ZeroMQ。它们是ZeroMQ API的一部分,在核心c++库中实现,并保证可以在所有优秀的零售商店中使用。 除此之外,我们还添加了高级消息传递模式。我们在ZeroMQ的基础上构建这些高级模式,并在应用程序中使用的任何语言中实现它们。它们不是核心库的一部分,不附带ZeroMQ包,并且作为ZeroMQ社区的一部分存在于它们自己的空间中。例如,我们在可靠的请求-应答模式中探索的Majordomo模式位于ZeroMQ组织中的GitHub Majordomo项目中。 在本书中,我们的目标之一是为您提供一组这样的高级模式,包括小型模式(如何明智地处理消息)和大型模式(如何构建可靠的发布子体系结构)。

处理消息(Working with Messages)

libzmq核心库实际上有两个api来发送和接收消息。我们已经看到和使用的zmq_send()和zmq_recv()方法都是简单的一行程序。我们将经常使用这些方法,但是zmq_recv()不擅长处理任意消息大小:它将消息截断为您提供的任何缓冲区大小。所以有第二个API与zmq_msg_t结构一起工作,它有一个更丰富但更困难的API:

- Initialise a message:

zmq_msg_init(),zmq_msg_init_size(),zmq_msg_init_data(). - Sending and receiving a message:

zmq_msg_send(),zmq_msg_recv(). - Release a message:

zmq_msg_close(). - 访问 message content:

zmq_msg_data(),zmq_msg_size(),zmq_msg_more(). - 处理消息属性 message properties:

zmq_msg_get(),zmq_msg_set(). - Message manipulation:

zmq_msg_copy(),zmq_msg_move().

在网络上,ZeroMQ消息是从零开始的任何大小的块,大小都适合存储在内存中。您可以使用协议缓冲区、msgpack、JSON或应用程序需要使用的任何其他东西来进行自己的序列化。选择一个可移植的数据表示形式是明智的,但是您可以自己做出关于权衡的决定。

在内存中,ZeroMQ消息是zmq_msg_t结构(或类,取决于您的语言)。下面是在C语言中使用ZeroMQ消息的基本规则:

- 创建并传递zmq_msg_t对象,而不是数据块。

- 要读取消息,可以使用zmq_msg_init()创建一个空消息,然后将其传递给zmq_msg_recv()。

- 要从新数据中编写一条消息,可以使用zmq_msg_init_size()创建一条消息,同时分配某个大小的数据块。然后使用memcpy填充数据,并将消息传递给zmq_msg_send()。

- 要释放(而不是销毁)消息,可以调用zmq_msg_close()。这将删除引用,最终ZeroMQ将销毁消息。

- 要访问消息内容,可以使用zmq_msg_data()。要知道消息包含多少数据,可以使用zmq_msg_size()。

- 不要使用zmq_msg_move()、zmq_msg_copy()或zmq_msg_init_data(),除非您阅读了手册页并确切地知道为什么需要这些。

- 您传递一个消息后zmq_msg_send(),ØMQ将clear 这个消息。i.e.,将大小设置为零。您不能两次发送相同的消息,并且不能在发送消息后访问消息数据。

- 如果您使用zmq_send()和zmq_recv(),而不是消息结构,这些规则将不适用。

如果您希望多次发送相同的消息,并且消息大小相当,那么创建第二个消息,使用zmq_msg_init()初始化它,然后使用zmq_msg_copy()创建第一个消息的副本。这不是复制数据,而是复制引用。然后可以发送消息两次(如果创建了更多副本,则可以发送两次或多次),并且只有在发送或关闭最后一个副本时才最终销毁消息。 ZeroMQ还支持多部分消息,它允许您以单个在线消息的形式发送或接收帧列表。这在实际应用程序中得到了广泛的应用,我们将在本章后面和高级请求-应答模式中对此进行研究。帧(在ZeroMQ参考手册页面中也称为“消息部件”)是ZeroMQ消息的基本有线格式。帧是指定长度的数据块。长度可以是0以上。如果您已经做过TCP编程,您就会明白为什么帧是“我现在应该读取多少关于这个网络socket的数据”这个问题的有用答案。

有一个称为ZMTP的线级协议,它定义了ZeroMQ如何在TCP连接上读写帧。如果您对它的工作原理感兴趣,那么这个规范非常简短。 最初,ZeroMQ消息是一个帧,就像UDP一样。稍后,我们使用多部分消息对此进行了扩展,这些消息非常简单,就是一系列帧,其中“more”位设置为1,然后是一个位设置为0的帧。然后ZeroMQ API允许您编写带有“more”标志的消息,当您读取消息时,它允许您检查是否有“more”。 因此,在底层ZeroMQ API和参考手册中,消息和帧之间存在一些模糊。所以这里有一个有用的词汇:

- 消息可以是一个或多个部分。

- 这些部分也被称为“框架”。

- 每个部分都是zmq_msg_t对象。

- 您在底层API中分别发送和接收每个部分。

- 高级api提供包装器来发送整个多部分消息。

还有一些关于信息值得了解的事情:

- 您可以发送零长度的消息,例如,从一个线程发送信号到另一个线程。

- ZeroMQ保证要不提供消息的所有部分(一个或多个),要不一个也不提供。

- ZeroMQ不会立即发送消息(单个或多个部分),而是在稍后某个不确定的时间。因此,多部分消息必须适合于内存。

- 消息(单个或多个部分)必须装入内存。如果您想发送任意大小的文件,您应该将它们分成几部分,并将每一部分作为单独的单部分消息发送。使用多部分数据不会减少内存消耗。

- 必须在接收到消息后调用zmq_msg_close(),使用的语言在范围关闭时不会自动销毁对象。发送消息后不会调用此方法。

重复一下,不要使用zmq_msg_init_data()。这是一种零拷贝的方法,肯定会给您带来麻烦。在您开始担心减少微秒之前,还有许多更重要的事情需要了解ZeroMQ。 使用这个丰富的API可能会很累。这些方法是针对性能而不是简单性进行优化的。如果你开始使用这些,你几乎肯定会弄错,直到你仔细阅读手册页。因此,一个好的语言绑定的主要工作之一就是将这个API封装在更容易使用的类中。

处理多个Sockets(Handling Multiple Sockets)

在到目前为止的所有例子中,大多数例子的主循环是:

- 1.等待套接字上的消息。

- 2.过程信息。

- 3.重复。

如果我们想同时读取多个端点呢?最简单的方法是将一个socket连接到所有端点,并让ZeroMQ为我们执行扇入。如果远程端点使用相同的模式,这是合法的,但是将PULL socket连接到PUB端点将是错误的。 要同时读取多个sockets,可以使用zmq_poll()。更好的方法可能是将zmq_poll()封装在一个框架中,该框架将其转换为一个不错的事件驱动的反应器,但是它的工作量比我们在这里要介绍的多得多。 让我们从一个脏的hack开始,部分原因是为了好玩,但主要是因为它让我向您展示如何进行非阻塞socket 读取。下面是一个使用非阻塞读取从两个sockets读取的简单示例。这个相当混乱的程序既是天气更新的订阅者,又是并行任务的工作人员:

msreader: Multiple socket reader in C

C++ | C# | Clojure | CL | Delphi | Erlang | F# | Felix | Go | Java | Lua | Objective-C | Perl | PHP | Python | Ruby | Scala | Tcl | Ada | Basic | Haskell | Haxe | Node.js | ooc | Q | Racket

这种方法的代价是对第一个消息(循环末尾的休眠,当没有等待消息要处理时)增加一些延迟。在亚毫秒级延迟非常重要的应用程序中,这将是一个问题。此外,您还需要检查nanosleep()或其他函数的文档,以确保它不繁忙循环。 您可以通过先读取一个套接字,然后读取第二个套接字来公平地对待套接字,而不是像我们在本例中所做的那样对它们进行优先级排序。 现在让我们看看同样毫无意义的小应用程序,使用zmq_poll(): mspoller: Multiple socket poller in C

C++ | C# | Clojure | CL | Delphi | Erlang | F# | Felix | Go | Haskell | Java | Lua | Node.js | Objective-C | Perl| PHP | Python | Ruby | Scala | Tcl | Ada | Basic | Haxe | ooc | Q | Racket The items structure has these four members:

typedef struct {void *socket; // ZeroMQ socket to poll onint fd; // OR, native file handle to poll onshort events; // Events to poll onshort revents; // Events returned after poll} zmq_pollitem_t;

多部分消息(Multipart Messages)

ZeroMQ让我们用几个帧组成一个消息,给我们一个“多部分消息”。现实的应用程序大量使用多部分消息,既用于包装带有地址信息的消息,也用于简单的序列化。稍后我们将查看回复信封。

我们现在要学习的只是如何盲目而安全地读写任何应用程序(例如代理)中的多部分消息,这些应用程序需要在不检查消息的情况下转发消息。

当你处理多部分消息时,每个部分都是zmq_msg项。例如,如果要发送包含五个部分的消息,必须构造、发送和销毁五个zmq_msg项。您可以预先执行此操作(并将zmq_msg项存储在数组或其他结构中),或者在发送它们时逐个执行。

这是我们如何发送帧在一个多部分的消息(我们接收每帧到一个消息对象):

zmq_msg_send (&message, socket, ZMQ_SNDMORE);…zmq_msg_send (&message, socket, ZMQ_SNDMORE);…zmq_msg_send (&message, socket, 0);

下面是我们如何接收和处理一个消息中的所有部分,无论是单个部分还是多个部分:

while (1) {zmq_msg_t message;zmq_msg_init (&message);zmq_msg_recv (&message, socket, 0);// Process the message frame…zmq_msg_close (&message);if (!zmq_msg_more (&message))break; // Last message frame}

关于多部分消息需要知道的一些事情:

- 当您发送一个多部分消息时,第一部分(以及所有后续部分)只有在您发送最后一部分时才实际通过网络发送。

- 如果您正在使用zmq_poll(),当您接收到消息的第一部分时,其他部分也都已经到达。

- 您将接收到消息的所有部分,或者完全不接收。

- 消息的每个部分都是一个单独的zmq_msg项。

- 无论是否选中more属性,都将接收消息的所有部分。

- 发送时,ZeroMQ将消息帧在内存中排队,直到最后一个消息帧被接收,然后将它们全部发送出去。

- 除了关闭套接字外,无法取消部分发送的消息。

中介和代理 Intermediaries and Proxies

ZeroMQ的目标是分散智能,但这并不意味着你的网络是中间的空白空间。它充满了消息感知的基础设施,通常,我们使用ZeroMQ构建该基础设施。ZeroMQ管道可以从很小的管道到成熟的面向服务的brokers。消息传递行业将此称为中介,即中间的内容处理任何一方。在ZeroMQ中,我们根据context调用这些代理、队列、转发器、设备或brokers。

这种模式在现实世界中极为常见,这也是为什么我们的社会和经济中充斥着中介机构,它们除了降低大型网络的复杂性和规模成本外,没有其他实际功能。真实的中介通常称为批发商、分销商、经理等等。

动态发现问题 The Dynamic Discovery Problem

在设计大型分布式架构时,您将遇到的问题之一是发现。也就是说,各个部分是如何相互了解的?这是特别困难的,如果部分来了又走了,所以我们称之为“动态发现问题”。

动态发现有几种解决方案。最简单的方法是通过硬编码(或配置)网络体系结构来完全避免这种情况,以便手工完成发现。也就是说,当您添加一个新片段时,您将重新配置网络以了解它。

图 12 - 小规模的发布-订阅网络(Small-Scale Pub-Sub Network)

在实践中,这将导致越来越脆弱和笨拙的体系结构。假设有一个发布者和100个订阅者。通过在每个订阅服务器中配置一个发布服务器端点,可以将每个订阅服务器连接到发布服务器。这很简单。用户是动态的;发布者是静态的。现在假设您添加了更多的发布者。突然间,它不再那么容易了。如果您继续将每个订阅者连接到每个发布者,那么避免动态发现的成本就会越来越高。

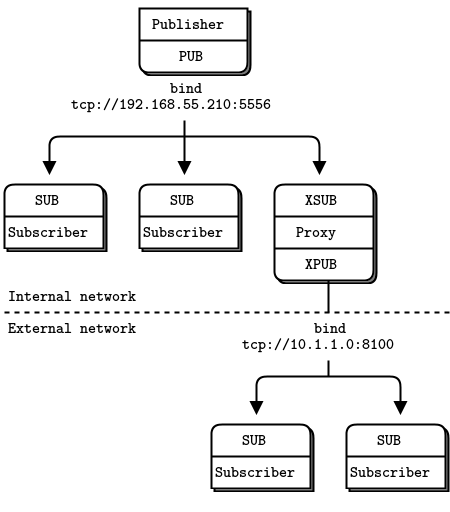

Figure 13 -使用代理的发布-订阅网络 Pub-Sub Network with a Proxy

对此有很多答案,但最简单的答案是添加中介;也就是说,网络中所有其他节点都连接到的一个静态点。在传统的消息传递中,这是消息代理的工作。ZeroMQ没有提供这样的消息代理,但是它让我们可以很容易地构建中介。

您可能想知道,如果所有网络最终都变得足够大,需要中介体,那么为什么不为所有应用程序设置一个message broker呢?对于初学者来说,这是一个公平的妥协。只要始终使用星型拓扑结构,忘记性能,事情就会正常工作。然而,消息代理是贪婪的;作为中央中介人,它们变得太复杂、太有状态,最终成为一个问题。

最好将中介看作简单的无状态消息交换机。一个很好的类比是HTTP代理;它在那里,但没有任何特殊的作用。在我们的示例中,添加一个 pub-sub代理解决了动态发现问题。我们在网络的“中间”设置代理。代理打开一个XSUB套接字、一个XPUB套接字,并将每个套接字绑定到已知的IP地址和端口。然后,所有其他进程都连接到代理,而不是彼此连接。添加更多订阅者或发布者变得很简单。

Figure 14 - Extended Pub-Sub

我们需要XPUB和XSUB套接字,因为ZeroMQ从订阅者到发布者执行订阅转发。XSUB和XPUB与SUB和PUB完全一样,只是它们将订阅公开为特殊消息。代理必须通过从XPUB套接字读取这些订阅消息并将其写入XSUB套接字,从而将这些订阅消息从订阅方转发到发布方。这是XSUB和XPUB的主要用例。

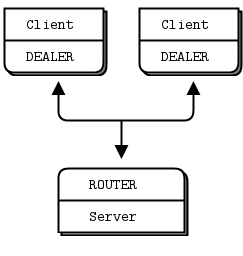

共享队列Shared Queue (DEALER and ROUTER sockets)

在Hello World客户机/服务器应用程序中,我们有一个客户机与一个服务通信。然而,在实际情况中,我们通常需要允许多个服务和多个客户机。这让我们可以扩展服务的功能(许多线程、进程或节点,而不是一个)。唯一的限制是服务必须是无状态的,所有状态都在请求中,或者在一些共享存储(如数据库)中。

Figure 15 -请求分发 Request Distribution

有两种方法可以将多个客户机连接到多个服务器。蛮力方法是将每个客户端套接字连接到多个服务端点。一个客户端套接字可以连接到多个服务套接字,然后REQ套接字将在这些服务之间分发请求。假设您将一个客户端套接字连接到三个服务端点;客户机请求R1、R2、R3、R4。R1和R4是服务A的,R2是服务B的,R3是服务C的。

这种设计可以让您更便宜地添加更多的客户端。您还可以添加更多的服务。每个客户端将其请求分发给服务。但是每个客户机都必须知道服务拓扑。如果您有100个客户机,然后决定再添加3个服务,那么您需要重新配置并重新启动100个客户机,以便客户机了解这3个新服务。

这显然不是我们想在凌晨3点做的事情,因为我们的超级计算集群已经耗尽了资源,我们迫切需要添加几百个新的服务节点。太多的静态部分就像液体混凝土:知识是分散的,你拥有的静态部分越多,改变拓扑结构的努力就越大。我们想要的是位于客户机和服务之间的东西,它集中了拓扑的所有知识。理想情况下,我们应该能够在任何时候添加和删除服务或客户机,而不需要触及拓扑的任何其他部分。

因此,我们将编写一个小消息队列代理来提供这种灵活性。代理绑定到两个端点,一个用于客户机的前端,一个用于服务的后端。然后,它使用zmq_poll()监视这两个sockets 的活动,当它有一些活动时,它在它的两个sockets 之间传递消息。它实际上并不明确地管理任何队列—zeromq在每个sockets 上自动管理队列。

当您使用REQ与REP对话时,您将得到一个严格同步的请求-应答对话框。客户端发送一个请求。服务读取请求并发送响应。然后客户端读取应答。如果客户机或服务尝试执行其他操作(例如,在不等待响应的情况下连续发送两个请求),它们将得到一个错误。

但是我们的代理必须是非阻塞的。显然,我们可以使用zmq_poll()来等待两个socket上的活动,但是不能使用REP和REQ。

Figure 16 - Extended Request-Reply

幸运的是,有两个名为DEALER和ROUTER的socket允许您执行非阻塞的请求-响应。在高级请求-应答模式中,您将看到商人和路由器套接字如何让您构建各种异步请求-应答流。现在,我们只需要看看DEALER 和ROUTER 如何让我们扩展REQ-REP跨一个中介,也就是我们的小broker。 在这个简单的扩展请求-应答模式中,REQ与ROUTER 对话,而DEALER 与REP对话。在DEALER 与ROUTER 之间,我们必须有代码(就像我们的broker一样)将消息从一个socket 中提取出来,并将它们推送到另一个socket 中。 request-reply broker绑定到两个端点,一个用于clients 连接(前端socket),另一个用于workers 连接(后端)。要测试此broker,您需要更改workers ,以便他们连接到后端socket。这是一个client ,我的意思是:

rrclient: Request-reply client in C

C++ | C# | Clojure | CL | Delphi | Erlang | F# | Go | Haskell | Haxe | Java | Lua | Node.js | Perl | PHP | Python | Racket | Ruby | Scala | Tcl | Ada | Basic | Felix | Objective-C | ooc | Q

Here is the worker: rrworker: Request-reply worker in C

C++ | C# | Clojure | CL | Delphi | Erlang | F# | Go | Haskell | Haxe | Java | Lua | Node.js | Perl | PHP | Python | Racket | Ruby | Scala | Tcl | Ada | Basic | Felix | Objective-C | ooc | Q

这是代理,它可以正确地处理多部分消息: rrbroker: Request-reply broker in C

C++ | C# | Clojure | CL | Delphi | Erlang | F# | Go | Haskell | Haxe | Java | Lua | Node.js | Perl | PHP | Python | Ruby | Scala | Tcl | Ada | Basic | Felix | Objective-C | ooc | Q | Racket

图 17 - Request-Reply Broker

使用请求-应答代理可以使客户机/服务器体系结构更容易伸缩,因为客户机看不到worker,而worker也看不到客户机。唯一的静态节点是中间的代理。

ZeroMQ的内置代理函数 ZeroMQ’s Built-In Proxy Function

原来,上一节的rrbroker中的核心循环非常有用,并且可以重用。它让我们可以毫不费力地构建pub-sub转发器和共享队列以及其他小型中介。ZeroMQ将其封装在一个方法中,zmq_proxy():

zmq_proxy (frontend, backend, capture);

zmq_proxy (frontend, backend, capture);

必须正确地连接、绑定和配置这两个(或者三个sockets,如果我们想捕获数据的话)。当我们调用zmq_proxy方法时,就像启动rrbroker的主循环一样。让我们重写 request-reply broker来调用zmq_proxy,并将其重新标记为一个听起来很昂贵的“消息队列”(人们已经为执行更少的代码向house收费):

msgqueue: Message queue broker in C

C++ | C# | Clojure | CL | Delphi | Erlang | F# | Go | Haskell | Haxe | Java | Lua | Node.js | Perl | PHP | Python | Q | Ruby | Tcl | Ada | Basic | Felix | Objective-C | ooc | Racket | Scala

如果您和大多数ZeroMQ用户一样,在这个阶段,您的思想开始思考,“如果我将随机的套接字类型插入代理,我能做什么坏事?”简单的回答是:试一试,看看发生了什么。实际上,您通常会坚持使用 ROUTER/DEALER、XSUB/XPUB或PULL/PUSH。

传输桥接 Transport Bridging

ZeroMQ用户经常会问,“我如何将我的ZeroMQ网络与技术X连接起来?”其中X是其他网络或消息传递技术。

图 18 - Pub-Sub Forwarder Proxy

答案很简单,就是建一座桥。桥接是一个小应用程序,它在一个socket上讲一个协议,并在另一个套接字上转换成 to/from第二个协议。协议解释器,如果你喜欢的话。ZeroMQ中常见的桥接问题是桥接两个传输或网络。 例如,我们将编写一个小代理,它位于发布者和一组订阅者之间,连接两个网络。前端socket (SUB)面向气象服务器所在的内部网络,后端(PUB)面向外部网络上的订阅者。它订阅前端socket 上的天气服务,并在后端socket 上重新发布数据。

wuproxy: Weather update proxy in C

C++ | C# | Clojure | CL | Delphi | Erlang | F# | Go | Haskell | Haxe | Java | Lua | Node.js | Perl | PHP | Python | Ruby | Scala | Tcl | Ada | Basic | Felix | Objective-C | ooc | Q | Racket

它看起来与前面的代理示例非常相似,但关键部分是前端和后端sockets 位于两个不同的网络上。例如,我们可以使用这个模型将组播网络(pgm传输)连接到tcp publisher。

处理错误和黑屏? Handling Errors and ETERM

ZeroMQ的错误处理哲学是快速故障和恢复能力的结合。我们认为,流程应该尽可能容易受到内部错误的攻击,并且尽可能健壮地抵御外部攻击和错误。打个比方,如果一个活细胞检测到一个内部错误,它就会自我毁灭,但它也会尽一切可能抵抗来自外部的攻击。

断言充斥着ZeroMQ代码,对于健壮的代码是绝对重要的;它们只需要在细胞壁的右边。应该有这样一堵墙。如果不清楚故障是内部的还是外部的,那就是需要修复的设计缺陷。在C/ c++中,断言一旦出现错误就立即停止应用程序。在其他语言中,可能会出现异常或暂停。

当ZeroMQ检测到外部故障时,它会向调用代码返回一个错误。在一些罕见的情况下,如果没有明显的策略来从错误中恢复,它会无声地删除消息。

到目前为止,我们看到的大多数C示例中都没有错误处理。真正的代码应该对每个ZeroMQ调用执行错误处理。如果您使用的是C之外的语言绑定,那么绑定可能会为您处理错误。在C语言中,你需要自己做这个。有一些简单的规则,从POSIX约定开始:

- 如果创建对象的方法失败,则返回NULL。

- 处理数据的方法可能返回已处理的字节数,或在出现错误或故障时返回-1。

- 其他方法在成功时返回0,在错误或失败时返回-1。

- 错误代码在errno或zmq_errno()中提供。

- zmq_strerror()提供了用于日志记录的描述性错误文本。

For example:

void *context = zmq_ctx_new ();assert (context);void *socket = zmq_socket (context, ZMQ_REP);assert (socket);int rc = zmq_bind (socket, "tcp://*:5555");if (rc == -1) {printf ("E: bind failed: %s\n", strerror (errno));return -1;}

有两个主要的例外情况,你应该作为非致命的处理:

- 当您的代码接收到带有ZMQ_DONTWAIT选项的消息并且没有等待的数据时,ZeroMQ将返回-1并再次将errno设置为EAGAIN。

- 当一个线程调用zmq_ctx_destroy(),而其他线程仍在执行阻塞工作时,zmq_ctx_destroy()调用关闭上下文,所有阻塞调用都以-1退出,errno设置为ETERM。

在C/ c++中,断言可以在经过优化的代码中完全删除,所以不要错误地将整个ZeroMQ调用封装在assert()中。它看起来整洁;然后优化器删除所有您想要执行的断言和调用,您的应用程序就会以令人印象深刻的方式崩溃。

图 19 - 带终止信号的并行管道Parallel Pipeline with Kill Signaling

让我们看看如何干净利落地关闭进程。我们将使用上一节中的并行管道示例。如果我们在后台启动了大量的worker,那么现在我们想在批处理完成时杀死它们。让我们通过发送一个kill消息给工人来实现这一点。最好的地方是sink,因为它知道批处理什么时候完成。 我们怎样把水槽和工人连接起来?推/拉插座是单向的。我们可以切换到另一种套接字类型,或者混合多个套接字流。让我们试试后者:使用发布-订阅模型向工人发送kill消息:

- sink 在新端点上创建一个PUB socket 。

- Workers 将他们的输入socket 连接到这个端点。

- 当sink 检测到批处理的结束时,它向其PUB socket 发送一个kill。

- 当Workers 检测到此终止消息时,它将退出。

sink不需要太多的新代码:

void *controller = zmq_socket (context, ZMQ_PUB);zmq_bind (controller, "tcp://*:5559");…// Send kill signal to workerss_send (controller, "KILL");

这是worker 进程,它使用我们前面看到的zmq_poll()技术管理两个sockets (一个获取任务的PULL socket和一个获取控制命令的SUB socket):

taskwork2: Parallel task worker with kill signaling in C

C++ | C# | Clojure | CL | Delphi | Erlang | F# | Go | Haskell | Haxe | Java | Lua | Node.js | Objective-C | Perl| PHP | Python | Ruby | Scala | Tcl | Ada | Basic | Felix | ooc | Q | Racket 下面是修改后的sink应用程序。当它收集完结果后,它会向所有workers发送一条“杀死”消息: tasksink2: Parallel task sink with kill signaling in C

C++ | C# | Clojure | CL | Delphi | Erlang | F# | Go | Haskell | Haxe | Java | Lua | Node.js | Objective-C | Perl| PHP | Python | Ruby | Scala | Tcl | Ada | Basic | Felix | ooc | Q | Racket

处理中断信号 Handling Interrupt Signals

当使用Ctrl-C或其他信号(如SIGTERM)中断时,实际应用程序需要干净地关闭。 默认情况下,这些操作只会杀死进程,这意味着不会刷新消息,不会干净地关闭文件,等等。

下面是我们如何处理不同语言的信号:

interrupt: Handling Ctrl-C cleanly in C

C++ | C# | Delphi | Erlang | Go | Haskell | Haxe | Java | Lua | Node.js | Perl | PHP | Python | Ruby | Scala | Ada | Basic | Clojure | CL | F# | Felix | Objective-C | ooc | Q | Racket | Tcl

该程序提供s_catch_signals(),它捕获Ctrl-C (SIGINT)和SIGTERM。当其中一个信号到达时,s_catch_signals()处理程序设置全局变量s_interrupted。由于您的信号处理程序,您的应用程序不会自动死亡。相反,你有机会收拾干净,优雅地离开。现在您必须显式地检查中断并正确地处理它。通过在主代码的开头调用s_catch_signals()(从interrupt.c复制)来实现这一点。这将设置信号处理。中断将影响ZeroMQ调用如下:

- 如果您的代码在阻塞调用(发送消息、接收消息或轮询)中阻塞,那么当信号到达时,调用将返回EINTR。

- 如果s_recv()之类的包装器被中断,则返回NULL。 因此,检查EINTR返回代码:NULL返回 and/or s_interrupted。 下面是一个典型的代码片段:

s_catch_signals ();client = zmq_socket (...);while (!s_interrupted) {char *message = s_recv (client);if (!message)break; // Ctrl-C used}zmq_close (client);

如果您调用s_catch_signals()而不测试中断,那么您的应用程序将对Ctrl-C和SIGTERM免疫,这可能有用,但通常不是。

检测内存泄漏 Detecting Memory Leaks

任何长时间运行的应用程序都必须正确地管理内存,否则最终会耗尽所有可用内存并崩溃。如果您使用的语言可以自动处理这一问题,那么恭喜您。如果您使用C或c++或任何其他负责内存管理的语言编写程序,这里有一个关于使用valgrind的简短教程,其中包括报告程序中出现的任何泄漏。

- To install valgrind, e.g., on Ubuntu or Debian, issue this command:

sudo apt-get install valgrind

- By default, ZeroMQ will cause valgrind to complain a lot. To remove these warnings, create a file called

vg.suppthat contains this:

{<socketcall_sendto>Memcheck:Paramsocketcall.sendto(msg)fun:send...}{<socketcall_sendto>Memcheck:Paramsocketcall.send(msg)fun:send...}

Fix your applications to exit cleanly after Ctrl-C. For any application that exits by itself, that’s not needed, but for long-running applications, this is essential, otherwise valgrind will complain about all currently allocated memory.

Build your application with

-DDEBUGif it’s not your default setting. That ensures valgrind can tell you exactly where memory is being leaked.Finally, run valgrind thus:

valgrind --tool=memcheck --leak-check=full --suppressions=vg.supp someprog

And after fixing any errors it reported, you should get the pleasant message:

==30536== ERROR SUMMARY: 0 errors from 0 contexts...

多线程与ZeroMQMultithreading with ZeroMQ

ZeroMQ可能是有史以来编写多线程(MT)应用程序的最好方法。而ZeroMQ sockets 需要一些调整,如果你习惯了传统sockets ,ZeroMQ多线程将采取你所知道的写MT应用程序的一切,把它扔到一个堆在花园里,浇上汽油,并点燃它。这是一本难得的值得一读的书,但是大多数关于并发编程的书都值得一读。

为了使MT程序完全完美(我的意思是字面意思),我们不需要互斥锁、锁或任何其他形式的线程间通信,除了通过ZeroMQ sockets 发送的消息。

所谓“完美的MT程序”,我的意思是代码易于编写和理解,在任何编程语言和任何操作系统中都可以使用相同的设计方法,并且可以跨任意数量的cpu伸缩,没有等待状态,没有收益递减点。

如果您花了多年的时间学习一些技巧,使MT代码能够正常工作,更不用说快速地使用锁、信号量和关键部分,那么当您意识到这一切都是徒劳时,您会感到厌恶。如果说我们从30多年的并发编程中学到了什么,那就是:不要共享状态。就像两个醉汉想要分享一杯啤酒。他们是不是好朋友并不重要。他们迟早会打起来的。你加的酒越多,他们就越会为了啤酒而打架。大多数MT应用程序看起来都像醉酒的酒吧斗殴。

在编写经典的共享状态MT代码时,如果不能将这些奇怪的问题直接转化为压力和风险,那就太可笑了,因为在压力下似乎可以工作的代码会突然失效。一家在bug代码方面拥有世界一流经验的大型公司发布了它的“多线程代码中的11个可能问题”列表,其中包括被遗忘的同步、不正确的粒度、读写撕裂、无锁重排序、锁保护、两步舞和优先级反转。

我们数了7道题,不是11道。但这不是重点。问题是,您真的希望运行电网或股票市场的代码在繁忙的周四下午3点开始得到两步锁定护送吗?谁在乎这些术语的实际含义呢?这并不是让我们转向编程的原因,而是用更复杂的黑客攻击来对抗更复杂的副作用。

尽管一些被广泛使用的模型是整个行业的基础,但它们从根本上是被破坏的,共享状态并发就是其中之一。想要无限扩展的代码就像互联网一样,发送消息,除了对坏掉的编程模型的普遍蔑视之外,什么也不分享。 你应该遵循一些规则来编写快乐的多线程代码与ZeroMQ:

- 在线程中单独隔离数据,永远不要在多个线程中共享数据。唯一的例外是ZeroMQ上下文,它是线程安全的。

- 远离经典的并发机制,如互斥、临界区、信号量等。这些是ZeroMQ应用程序中的反模式。

- 在进程开始时创建一个ZeroMQ上下文,并将其传递给希望通过inproc套接字连接的所有线程。

- 使用附加线程在应用程序中创建结构,并使用inproc上的PAIR sockets将这些线程连接到它们的父线程。模式是:绑定父socket,然后创建连接其socket的子线程。

- 使用分离的线程模拟独立的任务,并使用它们自己的contexts。通过tcp连接这些。稍后,您可以将它们转移到独立进程,而不需要显著更改代码。

- 线程之间的所有交互都以ZeroMQ消息的形式发生,您可以或多或少地正式定义它。

- 不要在线程之间共享ZeroMQ socket。ZeroMQ socket不是线程安全的。从技术上讲,可以将socket从一个线程迁移到另一个线程,但这需要技巧。在线程之间共享socket的惟一合理的地方是语言绑定,它需要像socket上的垃圾收集那样做。

例如,如果需要在应用程序中启动多个代理,则希望在它们各自的线程中运行每个代理。在一个线程中创建代理前端和后端socket,然后将socket传递给另一个线程中的代理,这很容易出错。这可能在一开始看起来有效,但在实际使用中会随机失败。记住:除非在创建socket的线程中,否则不要使用或关闭socket。

如果遵循这些规则,就可以很容易地构建优雅的多线程应用程序,然后根据需要将线程拆分为单独的进程。应用程序逻辑可以位于线程、进程或节点中:无论您的规模需要什么。 ZeroMQ使用本机OS线程,而不是虚拟的“绿色”线程。其优点是您不需要学习任何新的线程API,而且ZeroMQ线程可以干净地映射到您的操作系统。您可以使用诸如Intel的ThreadChecker之类的标准工具来查看您的应用程序在做什么。缺点是本地线程api并不总是可移植的,而且如果您有大量的线程(数千个),一些操作系统将会受到压力。

让我们看看这在实践中是如何工作的。我们将把原来的Hello World服务器变成更强大的服务器。原始服务器在一个线程中运行。如果每个请求的工作很低,很好:一个ØMQ线程CPU核心可以全速运行,没有等待,做了很多的工作。但是,实际的服务器必须对每个请求执行重要的工作。当10,000个客户机同时攻击服务器时,单个内核可能还不够。因此,一个实际的服务器将启动多个工作线程。然后,它以最快的速度接受请求,并将这些请求分发给它的工作线程。工作线程在工作中不断地工作,并最终将它们的响应发送回去。

当然,您可以使用代理代理和外部工作进程来完成所有这些操作,但是启动一个占用16个内核的进程通常比启动16个进程(每个进程占用一个内核)更容易。此外,将worker作为线程运行将减少网络跳、延迟和网络流量。Hello World服务的MT版本基本上将代理和worker分解为一个进程:

mtserver: Multithreaded service in C

C++ | C# | Clojure | CL | Delphi | Erlang | F# | Go | Haskell | Haxe | Java | Lua | Perl | PHP | Python | Q | Ruby | Scala | Ada | Basic | Felix | Node.js | Objective-C | ooc | Racket | Tcl

到目前为止,所有代码都应该是你能看懂的。它是如何工作的:

- 服务器启动一组工作线程。每个工作线程创建一个REP socket,然后在这个socket上处理请求。工作线程就像单线程服务器。唯一的区别是传输(inproc而不是tcp)和绑定连接方向。

- 服务器创建一个 ROUTER socket来与clients 通信,并将其绑定到外部接口(通过tcp)。

- 服务器创建一个 DEALER socket来与工人对话,并将其绑定到其内部接口(通过inproc)。

- 服务器启动连接两个sockets的代理。代理从所有客户端公平地提取传入请求,并将这些请求分发给工作人员。它还将回复路由回它们的原点。

注意,在大多数编程语言中,创建线程是不可移植的。POSIX库是pthreads,但是在Windows上必须使用不同的API。在我们的示例中,pthread_create调用启动一个运行我们定义的worker_routine函数的新线程。我们将在 Advanced Request-Reply Patterns中看到如何将其封装到可移植API中。

这里的“工作”只是一秒钟的停顿。我们可以在worker中做任何事情,包括与其他节点通信。 这就是MT服务器在ØMQsockets 和节点方面的样子请注意 request-reply 链是如何表示为REQ-ROUTER-queue-DEALER-REP。

线程之间的通信Signaling Between Threads (PAIR Sockets)

当您开始使用ZeroMQ创建多线程应用程序时,您将遇到如何协调线程的问题。尽管您可能想要插入“sleep”语句,或者使用多线程技术(如信号量或互斥锁),但是您应该使用的惟一机制是ZeroMQ消息。记住酒鬼和啤酒瓶的故事。

让我们创建三个线程,当它们准备好时互相发出信号。在这个例子中,我们在inproc传输上使用 PAIR sockets:

mtrelay: Multithreaded relay in C

C++ | C# | Clojure | CL | Delphi | Erlang | F# | Go | Haskell | Haxe | Java | Lua | Perl | PHP | Python | Q | Ruby | Scala | Ada | Basic | Felix | Node.js | Objective-C | ooc | Racket | Tcl

Figure 21 - 接力赛The Relay Race

这是一个经典的模式多线程与ZeroMQ:

- 1.两个线程使用共享context,通过inproc进行通信。

- 2.父线程创建一个socket,将其绑定到inproc://端点,然后启动子线程,将context传递给它。 子线程创建第二个socket,将其连接到inproc://端点,然后向父线程发出准备就绪的信号。

注意,使用此模式的多线程代码不能扩展到进程。如果您使用inproc和 socket pairs,那么您正在构建一个紧密绑定的应用程序,即,其中线程在结构上相互依赖。当低延迟非常重要时,执行此操作。另一种设计模式是松散绑定的应用程序,其中线程有自己的context ,并通过ipc或tcp进行通信。您可以轻松地将松散绑定的线程拆分为单独的进程。 这是我们第一次展示使用 PAIR sockets的示例。为什么使用PAIR?其他socket 组合似乎也有效果,但它们都有副作用,可能会干扰信号:

- 您可以使用PUSH作为发送方,PULL作为接收方。这看起来很简单,也很有效,但是请记住PUSH将向所有可用的接收者分发消息。如果你不小心启动了两个接收器(例如,你已经启动了一个接收器,然后你又启动了另一个接收器),你将“丢失”一半的信号。PAIR 具有拒绝多个连接的优势;这个PAIR 是独一无二的。

- 您可以使用DEALER作为发送方,使用 ROUTER 作为接收方。ROUTER ,然而,将你的消息包装在一个“信封”,这意味着你的零大小的信号变成一个多部分的消息。如果您不关心数据并将任何内容视为有效信号,如果您从socket中读取的次数不超过一次,那么这就无关紧要了。然而,如果你决定发送真实的数据,你会突然发现ROUTER提供给你“错误”的消息。DEALER 还分发outgoing 的消息,像PUSH一样带来相同的风险。

- 您可以将PUB用于发送方,将SUB用于接收方。这将正确地发送您的邮件,就像您发送邮件一样,PUB不会像PUSH或DEALER那样分发但是,您需要使用空订阅来配置订阅者,这很烦人。 由于这些原因,PAIR是线程对之间协调的最佳选择。

节点的协调Node Coordination

当您想要协调网络上的一组节点时,PAIR sockets将不再有效。这是少数几个线程和节点策略不同的领域之一。基本上,节点来来去去,而线程通常是静态的。如果远程节点离开并返回, PAIR sockets不会自动重新连接。

Figure 22 - 发布-订阅同步Pub-Sub Synchronization

线程和节点之间的第二个显著差异是,通常有固定数量的线程,但节点的数量更可变。让我们以前面的一个场景(天气服务器和客户机)为例,使用节点协调确保订阅者在启动时不会丢失数据。

以下是应用程序的工作原理:

- 发布者预先知道它希望有多少订阅者。这是一个神奇的数字。

- 发布者启动并等待所有订阅者连接。这是节点协调部分。每个订阅者订阅,然后通过另一个socket告诉发布者它已经准备好了。

- 当发布者连接了所有订阅者后,它开始发布数据。 在本例中,我们将使用REQ-REP套接字流来同步订阅者和发布者。以下是出版商:

syncpub: Synchronized publisher in C

C++ | C# | Clojure | CL | Delphi | Erlang | F# | Go | Haskell | Haxe | Java | Lua | Node.js | Perl | PHP | Python | Racket | Ruby | Scala | Tcl | Ada | Basic | Felix | Objective-C | ooc | Q

And here is the subscriber: syncsub: Synchronized subscriber in C

C++ | C# | Clojure | CL | Delphi | Erlang | F# | Go | Haskell | Haxe | Java | Lua | Node.js | Perl | PHP | Python | Racket | Ruby | Scala | Tcl | Ada | Basic | Felix | Objective-C | ooc | Q

这个Bash shell脚本将启动10个订阅者,然后是发布者:

echo "Starting subscribers..."for ((a=0; a<10; a++)); dosyncsub &doneecho "Starting publisher..."syncpub

这就得到了令人满意的结果:

Starting subscribers...Starting publisher...Received 1000000 updatesReceived 1000000 updates...Received 1000000 updatesReceived 1000000 updates

我们不能假设SUB connect将在REQ/REP对话框完成时完成。如果使用除inproc之外的任何传输,则不能保证出站连接将以任何顺序完成。因此,该示例在订阅和发送REQ/REP同步之间强制休眠一秒钟。

一个更健壮的模型可以是:

- Publisher打开PUB socket 并开始发送“Hello”消息(而不是数据)。

- 订阅者连接SUB socket ,当他们收到一条Hello消息时,他们通过 REQ/REP socket pair告诉发布者。

- 当发布者获得所有必要的确认后,它就开始发送实际数据。

零拷贝Zero-Copy

ZeroMQ的消息API允许您直接从应用程序缓冲区发送和接收消息,而不需要复制数据。 我们称之为零拷贝,它可以在某些应用程序中提高性能。

您应该考虑在以高频率发送大内存块(数千字节)的特定情况下使用zero-copy。对于短消息或较低的消息率,使用零拷贝将使您的代码更混乱、更复杂,并且没有可度量的好处。像所有优化一样,当您知道它有帮助时使用它,并在前后进行度量。

要执行zero-copy,可以使用zmq_msg_init_data()创建一条消息,该消息引用已经用malloc()或其他分配器分配的数据块,然后将其传递给zmq_msg_send()。创建消息时,还传递一个函数,ZeroMQ在发送完消息后将调用该函数释放数据块。这是最简单的例子,假设buffer是一个在堆上分配了1000字节的块:

void my_free (void *data, void *hint) {free (data);}// Send message from buffer, which we allocate and ZeroMQ will free for uszmq_msg_t message;zmq_msg_init_data (&message, buffer, 1000, my_free, NULL);zmq_msg_send (&message, socket, 0);

注意,发送消息后不调用zmq_msg_close()—libzmq在实际发送消息后将自动调用zmq_msg_close()。

没有办法在接收时执行零复制:ZeroMQ提供了一个缓冲区,您可以存储任意长的缓冲区,但是它不会直接将数据写入应用程序缓冲区。

在编写时,ZeroMQ的多部分消息与zero-copy很好地结合在一起。在传统的消息传递中,需要将不同的缓冲区组合到一个可以发送的缓冲区中。这意味着复制数据。使用ZeroMQ,您可以将来自不同来源的多个缓冲区作为单独的消息帧发送。将每个字段作为长度分隔的帧发送。对于应用程序,它看起来像一系列发送和接收调用。但是在内部,多个部分被写到网络中,并通过单个系统调用进行读取,因此非常高效。

发布-订阅消息信封Pub-Sub Message Envelopes

在 pub-sub 模式中,我们可以将密钥拆分为一个单独的消息框架,称为信封。如果你想使用pub-sub信封,那就自己做吧。它是可选的,在之前的 pub-sub例子中我们没有这样做。 对于简单的情况,使用 pub-sub信封要多做一些工作,但是对于实际情况,尤其是键和数据是自然分离的情况,使用它会更简洁。

Figure 23 - Pub-Sub Envelope with Separate Key

订阅执行前缀匹配。也就是说,它们查找“所有以XYZ开头的消息”。一个明显的问题是:如何将键与数据分隔开来,以便前缀匹配不会意外匹配数据。最好的答案是使用信封,因为匹配不会跨越框架边界。下面是一个极简示例,展示了 pub-sub信封在代码中的外观。此发布者发送两种类型的消息,A和B。

The envelope holds the message type:

psenvpub: Pub-Sub envelope publisher in C

C++ | C# | Clojure | CL | Delphi | Erlang | F# | Go | Haskell | Haxe | Java | Lua | Node.js | Perl | PHP | Python | Ruby | Scala | Tcl | Ada | Basic | Felix | Objective-C | ooc | Q | Racket The subscriber wants only messages of type B: psenvsub: Pub-Sub envelope subscriber in C

C++ | C# | Clojure | CL | Delphi | Erlang | F# | Go | Haskell | Haxe | Java | Lua | Node.js | Perl | PHP | Python | Ruby | Scala | Tcl | Ada | Basic | Felix | Objective-C | ooc | Q | Racket

When you run the two programs, the subscriber should show you this:

[B] We would like to see this[B] We would like to see this[B] We would like to see this...

此示例显示订阅筛选器拒绝或接受整个多部分消息(键和数据)。您永远不会得到多部分消息的一部分。如果您订阅了多个发布者,并且希望知道它们的地址,以便能够通过另一个socket (这是一个典型的用例)向它们发送数据,那么创建一个由三部分组成的消息。

Figure 24 - Pub-Sub Envelope with Sender Address

High-Water Marks

当您可以快速地从一个进程发送消息到另一个进程时,您很快就会发现内存是一种宝贵的资源,并且可以被轻松地填满。流程中某些地方的几秒钟延迟可能会变成积压,导致服务器崩溃,除非您了解问题并采取预防措施。

问题是这样的:假设您有一个进程A以很高的频率向正在处理它们的进程B发送消息。突然,B变得非常繁忙(垃圾收集、CPU过载等等),短时间内无法处理消息。对于一些繁重的垃圾收集,可能需要几秒钟的时间,或者如果有更严重的问题,可能需要更长的时间。进程A仍然试图疯狂发送的消息会发生什么情况?有些将位于B的网络缓冲区中。有些将位于以太网线路本身。有些将位于A的网络缓冲区中。其余的会在A的内存中积累,就像A后面的应用程序发送它们一样快。如果不采取一些预防措施,A很容易耗尽内存并崩溃。

这是消息代理的一个一致的经典问题。更糟糕的是,从表面上看,这是B的错,而B通常是a无法控制的用户编写的应用程序。

答案是什么?一是把问题往上游推。A从其他地方获取信息。所以告诉这个过程,“停止!”等等。这叫做流量控制。这听起来很有道理,但是如果你在Twitter上发消息呢?你会告诉全世界的人在B行动起来的时候停止发推吗?

流程控制在某些情况下有效,但在其他情况下无效。运输层不能告诉应用层“停止”,就像地铁系统不能告诉大型企业“请让您的员工再工作半个小时”一样。我太忙了”。消息传递的解决方案是设置缓冲区大小的限制,然后当达到这些限制时,采取一些明智的行动。在某些情况下(不是地铁系统),答案是扔掉信息。在另一些国家,最好的策略是等待。

ZeroMQ使用HWM(高水位)的概念来定义其内部管道的容量。每个socket 外或socket 内的连接都有自己的管道和用于发送和/或接收的HWM,这取决于socket 类型。一些socket (PUB, PUSH)只有发送缓冲区。有些(SUB、PULL、REQ、REP)只有接收缓冲区。一些(DEALER, ROUTER, PAIR)有发送和接收缓冲区。

In ZeroMQ v2.x, HWM默认为无穷大。这很容易做到,但对于高容量publishers来说,通常也是致命的。In ZeroMQ v3.x,默认设置为1000,这样更合理。如果你还在用ZeroMQ v2.x,你应该总是在你的socket 上设置一个HWM,设置成1000或另一个考虑您的信息大小和预期的用户性能的数字来匹配ZeroMQ v3.x。

当socket 到达其HWM时,它将根据socket 类型阻塞或删除数据。如果PUB和ROUTER socket 到达它们的HWM,它们将丢弃数据,而其他 socket 类型将阻塞。在inproc传输中,发送方和接收方共享相同的缓冲区,因此实际的HWM是双方设置的HWM的和。最后,HWMs并不精确;由于libzmq实现其队列的方式,默认情况下最多可以获得1,000条消息,但实际缓冲区大小可能要小得多(只有一半)。

缺少消息问题的解决者(解决方式)Missing Message Problem Solver

在使用ZeroMQ构建应用程序时,您将不止一次地遇到这个问题:丢失预期接收到的消息。 我们已经整理了一个图表,介绍了造成这种情况的最常见原因。

Figure 25 - Missing Message Problem Solver

下面是图表的摘要:

- 在 SUB sockets上,使用zmq_setsockopt()和ZMQ_SUBSCRIBE设置订阅,否则将不会收到消息。因为您通过前缀订阅消息,如果您订阅“”(空订阅),您将获得所有内容。

- 如果您启动 SUB sockets(即在PUB socket开始发送数据之后,您将丢失连接之前发布的任何内容。如果这是一个问题,请设置您的体系结构,以便首先启动 SUB sockets,然后PUB socket开始发布。

- 即使同步了 SUB 和 PUB socket,仍然可能丢失消息。这是因为在实际创建连接之前不会创建内部队列。如果您可以切换绑定/连接方向,以便 SUB socket 绑定,而PUB socket连接,您可能会发现它的工作方式与您所期望的一样。

- 如果您使用REP和REQsockets,并且没有坚持同步发送/recv/send/recv命令,ZeroMQ将报告错误,您可能会忽略这些错误。然后,看起来就像是你在丢失信息。如果您使用REQ或REP,请坚持send/recv顺序,并且始终在实际代码中检查ZeroMQ调用中的错误。

- 如果使用 PUSH sockets,您会发现第一个连接的PULL socket 将获取不公平的消息共享。只有在成功连接所有PULL套接字时才会发生准确的消息轮换,这可能需要几毫秒的时间。作为PUSH / PULL的替代方案,对于较低的数据速率,请考虑使用ROUTER / DEALER和负载平衡模式。

- 如果您正在跨线程共享sockets ,请不要这样做。这将导致随机的怪异,并崩溃。

- 如果使用inproc,请确保两个socket位于相同的context中。否则,连接端实际上会失败。同样,先绑定,然后连接。inproc不像tcp那样是一个断开连接的传输。

- 如果您正在使用ROUTER sockets,通过发送不正确的身份帧(或忘记发送身份帧),很容易意外丢失消息。通常,在 ROUTER sockets 上设置ZMQ_ROUTER_MANDATORY选项是一个好主意,但是也要在每次发送调用时检查返回代码。

- 最后,如果您真的不知道哪里出了问题,那么就创建一个最小的测试用例来重现问题,并向ZeroMQ社区寻求帮助。

Chapter 3 -高级 Advanced Request-Reply Patterns

在第2章-Sockets and Patterns 中,我们通过开发一系列小型应用程序来学习使用ZeroMQ的基础知识,每次都要探索ZeroMQ的新方面。在本章中,我们将继续使用这种方法,探索构建在ZeroMQ核心请求-应答模式之上的高级模式。

我们将讨论:

- 请求-应答机制如何工作

- 如何组合REQ、REP、DEALER和 ROUTER sockets

- ROUTER sockets如何工作,详细的讨论

- 负载平衡模式

- 构建一个简单的负载平衡消息代理

- 为ZeroMQ设计一个高级API

- 构建异步请求-应答服务器

- 一个详细的代理间路由示例

The Request-Reply Mechanisms(机制)

我们已经简要介绍了多部分消息。现在让我们看一个主要的用例,即回复消息信封。信封是一种用地址安全包装数据的方法,而不需要接触数据本身。通过将回复地址分离到信封中,我们可以编写通用的中介,如api和代理,无论消息有效负载或结构是什么,它们都可以创建、读取和删除地址。

在请求-应答模式中,信封包含应答的返回地址。这就是没有状态的ZeroMQ网络如何创建往返的请求-应答对话框。

当您使用REQ和REP sockets 时,您甚至看不到信封;这些sockets 自动处理它们。但是对于大多数有趣的请求-应答模式,您需要了解信封,特别是ROUTER sockets。我们会一步一步来。

The Simple Reply Envelope

请求-应答交换由请求消息和最终的应答消息组成。在简单的请求-应答模式中,每个请求都有一个应答。在更高级的模式中,请求和响应可以异步流动。然而,回复信封总是以相同的方式工作。

ZeroMQ应答信封正式由零个或多个应答地址组成,后跟一个空帧(信封分隔符),后跟消息体(零个或多个帧)。信封是由多个sockets 在一个链中一起工作创建的。我们来分解一下。

我们将从通过REQsocket发送“Hello”开始。REQ套接字创建了最简单的回复信封,它没有地址,只有一个空的分隔符框架和包含“Hello”字符串的消息框架。这是一个两帧的消息。

Figure 26 - Request with Minimal Envelope

REP socket执行匹配工作:它剥离信封,直到并包括分隔符框架,保存整个信封,并将“Hello”字符串传递给应用程序。因此,我们最初的Hello World示例在内部使用了请求-回复信封,但是应用程序从未看到过它们。

如果您监视在hwclient和hwserver之间流动的网络数据,您将看到:每个请求和每个响应实际上是两个帧,一个空帧,然后是主体。这对于一个简单的REQ-REP对话框似乎没有多大意义。不过,当我们探讨ROUTER和DEALER 如何处理信封时,您将会看到原因。

加长回信信封The Extended Reply Envelope

现在,让我们使用中间的 ROUTER-DEALER代理扩展 REQ-REP对 ,看看这会如何影响回复信封。这是我们在Chapter 2 - Sockets and Patterns中已经看到的扩展请求-应答模式。实际上,我们可以插入任意数量的代理步骤。机制是一样的。

Figure 27 - Extended Request-Reply Pattern

代理在伪代码中这样做:

prepare context, frontend and backend socketswhile true:poll on both socketsif frontend had input:read all frames from frontendsend to backendif backend had input:read all frames from backendsend to frontend

与其他socket不同,ROUTER socket跟踪它所拥有的每个连接,并将这些信息告诉调用者。 它告诉调用者的方法是将连接标识粘贴到接收到的每个消息前面。 标识(有时称为地址)只是一个二进制字符串,除了“这是连接的惟一句柄”之外没有任何意义。 然后,当您通过ROUTER socket发送消息时,您首先发送一个标识帧。

zmq_socket()手册页这样描述它:

当接收到消息时,ZMQ_ROUTER socket 在将消息传递给应用程序之前,应该在消息部分前加上一个包含消息的原始对等点标识的消息部分。接收到的消息在所有连接的对等点之间公平排队。发送消息时,ZMQ_ROUTER socket 应删除消息的第一部分,并使用它来确定消息应路由到的对等方的身份。

作为历史记录,ZeroMQ v2.2和更早的版本使用uuid作为标识。ZeroMQ v3.0和以后的版本在默认情况下生成一个5字节的标识(0 +一个随机32位整数)。这对网络性能有一定的影响,但仅当您使用多个代理跃点时,这种情况很少见。主要的更改是通过删除对UUID库的依赖来简化libzmq的构建。

身份是一个很难理解的概念,但如果你想成为ZeroMQ专家,它是必不可少的。 ROUTER socket 为它工作的每个连接创建一个随机标识。如果有三个 REQ sockets连接到ROUTER socket,它将为每个REQ sockets创建一个随机标识。 如果我们继续我们的工作示例,假设REQsocket有一个3字节的标识ABC。在内部,这意味着ROUTER socket保留一个哈希表,它可以在这个哈希表中搜索ABC并为REQsocket找到TCP连接。当我们从ROUTER socket接收消息时,我们得到三个帧。

Figure 28 - Request with One Address

代理循环的核心是“从一个socket读取,向另一个socket写入”,因此我们将这三帧发送到ROUTER socket上。如果您现在嗅探网络流量,您将看到这三个帧从DEALER socket飞向REP socket。REP socket和前面一样,去掉整个信封,包括新的回复地址,并再次向调用者传递“Hello”。顺便提一下,REP socket一次只能处理一个请求-应答交换,这就是为什么如果您尝试读取多个请求或发送多个响应而不坚持严格的recv-send循环,它会给出一个错误。 您现在应该能够可视化返回路径。当hwserver将“World”发送回来时,REP socket将其与它保存的信封打包,并通过网络向DEALER socket发送一个三帧回复消息。

Figure 29 - Reply with one Address

现在DEALER 读取这三帧,并通过 ROUTER socket发送所有这三帧。 ROUTER接受消息的第一帧,即ABC标识,并为此查找连接。如果它发现了,它就会把接下来的两帧泵到网络上。

Figure 30 - Reply with Minimal Envelope

REQ socket 接收此消息,并检查第一帧是否为空分隔符,它就是空分隔符。REQ socket 丢弃了框架并将“World”传递给调用应用程序,该应用程序将它打印出来,这让第一次看到ZeroMQ的年轻一代感到惊讶。

What’s This Good For?

说实话,用于严格请求-应答或扩展请求-应答的用例在某种程度上是有限的。首先,没有简单的方法可以从常见的故障中恢复,比如由于应用程序代码错误导致服务器崩溃。我们将在可靠的请求-应答模式中看到更多这方面的内容。然而,一旦你掌握了这四个sockets 处理信封的方式,以及它们之间的通信方式,你就可以做一些非常有用的事情。我们了解了ROUTER 如何使用应答信封来决定将应答路由回哪个客户机REQ socket 。现在让我们用另一种方式来表达:

- 每次ROUTER 给你一个消息,它会告诉你来自哪个对等点,作为一个身份。

- 您可以将其与散列表一起使用(以标识为键),以便在新对等点到达时跟踪它们。

- 如果将标识前缀作为消息的第一帧,ROUTER 将异步地将消息路由到连接到它的任何对等点。 ROUTER sockets并不关心整个信封。他们对空分隔符一无所知。他们所关心的只是一个身份框架,这个框架让他们知道要向哪个连接发送消息。

(概述)Recap of Request-Reply Sockets

让我们来总结一下:

- REQ socket向网络发送消息数据前面的空分隔符帧。REQ socket是同步的。REQ socket总是发送一个请求,然后等待一个响应。REQ socket每次只与一个对等点通信。如果您将一个REQ socket连接到多个对等点,则请求将被分发到每个对等点,并期望每个对等点一次发送一个响应。

- REP socket读取并保存所有标识帧,直到并包括空分隔符,然后将以下一帧或多帧传递给调用方。 REP socket是同步的,每次只与一个对等点通信。如果您将一个 REP socket连接到多个对等点,则以公平的方式从对等点读取请求,并且始终将响应发送到发出最后一个请求的同一对等点。

- DEALER socket不理会回复信封,并像处理任何多部分消息一样处理此消息。DEALER socket是异步的,就像PUSH and PULL 的组合。它们在所有连接之间分发发送的消息,并且公平队列接收来自所有连接的消息。

- ROUTER socket 不理会回复信封,就像DEALER一样。它为其连接创建标识,并将这些标识作为任何接收到的消息中的第一帧传递给调用者。相反,当调用者发送消息时,它使用第一个消息帧作为标识来查找要发送到的连接。 ROUTERS是异步的。

Request-Reply Combinations(组合)

我们有四个 request-reply sockets,每个sockets具有特定的行为。我们已经看到它们如何以简单和扩展的请求-应答模式连接。但是这些sockets是您可以用来解决许多问题的构建块。 这些是合法的组合:

- REQ to REP

- DEALER to REP

- REQ to ROUTER

- DEALER to ROUTER

- DEALER to DEALER

- ROUTER to ROUTER

And these combinations are invalid (and I’ll explain why):

- REQ to REQ

- REQ to DEALER

- REP to REP

- REP to ROUTER

下面是一些记忆语义的技巧。DEALER 类似于异步REQ socket,而ROUTER 类似于异步REP socket。在我们使用REQ socket的地方,我们可以使用一个DEALER ;我们只需要自己读和写信封。在使用REP socket的地方,我们可以使用ROUTER ;我们只需要自己管理身份。将REQ和DEALER socket视为“客户端”,而REP和ROUTER socket视为“服务器”。大多数情况下,您需要绑定REP和ROUTER socket,并将REQ和DEALER socket连接到它们。它并不总是这么简单,但它是一个干净而令人难忘的起点。

The REQ to REP Combination

我们已经介绍了一个与REP服务器对话的REQ客户机,但是让我们看一个方面:REQ客户机必须启动消息流。代表服务器不能与未首先向其发送请求的REQ客户机通信。从技术上讲,这甚至是不可能的,如果您尝试了,API还会返回一个EFSM错误。

The DEALER to REP Combination

现在,让我们用DEALER替换REQ客户端。这为我们提供了一个异步客户机,它可以与多个 REP服务器通信。如果我们使用DEALER重写“Hello World”客户端,我们就可以发送任意数量的“Hello”请求,而不需要等待回复。

当我们使用一个DEALER 与一个REP socket通信时,我们必须准确地模拟REQ socket将发送的信封,否则REP socket将把消息作为无效丢弃。所以,为了传递信息,我们:

- 发送一个设置了更多标志的空消息帧;然后

- 发送消息体。

当我们收到信息时,我们:

- 接收第一个帧,如果它不是空的,则丢弃整个消息;

- 接收下一帧并将其传递给应用程序。

The REQ to ROUTER Combination

就像我们可以用DEALER替换REQ一样,我们也可以用ROUTER替换REP。这为我们提供了一个异步服务器,它可以同时与多个REQ客户机通信。如果我们使用ROUTER重写“Hello World”服务器,我们将能够并行处理任意数量的“Hello”请求。我们在 Chapter 2 - Sockets and Patterns mtserver示例中看到了这一点。我们可以用两种不同的方式使用ROUTER:

- 作为在前端和后端sockets之间切换消息的代理。

- 作为读取消息并对其进行操作的应用程序。

在第一种情况下,ROUTER 只是读取所有帧,包括人工身份帧,然后盲目地传递它们。在第二种情况下,ROUTER 必须知道它正在发送的回复信封的格式。由于另一个对等点是REQ socket,ROUTER 获得标识帧、空帧和数据帧。

The DEALER to ROUTER Combination

现在,我们可以切换REQ和REP与DEALER 和ROUTER ,以获得最强大的socket 组合,这是DEALER 与ROUTER 交谈。它为我们提供了与异步服务器通信的异步客户机,在异步服务器上,双方都完全控制消息格式。

因为DEALER 和ROUTER 都可以处理任意的消息格式,如果您希望安全地使用这些格式,您必须成为一个协议设计人员。至少您必须决定是否要模拟REQ/REP回复信封。这取决于你是否真的需要发送回复。

The DEALER to DEALER Combination

您可以用ROUTER交换一个REP ,但也可以用一个DEALER交换一个REP ,前提是DEALER只与一个同行通信。

当您将REP 替换为DEALER时,您的worker 可以突然完全异步,发送任意数量的回复。这样做的代价是你必须自己管理回复信封,并把它们处理好,否则什么都不管用。稍后我们将看到一个工作示例。就目前而言,DEALER 对DEALER 模式是一种比较棘手的模式,值得庆幸的是,我们很少需要这种模式。

| The ROUTER to ROUTER Combination | top prev next |

|---|---|

对于N-to-N连接,这听起来很完美,但是这是最难使用的组合。在使用ZeroMQ之前,您应该避免使用它。我们将在自由模式和 Reliable Request-Reply 模式中看到一个例子,以及为分布式计算框架中的点对点工作设计的DEALER to ROUTER 的另一种替代方案(and an alternative DEALER to ROUTER design for peer-to-peer work in A Framework for Distributed Computing.)。

Invalid Combinations

大多数情况下,试图将客户端连接到客户端或服务器连接到服务器是一个坏主意,不会奏效。不过,我不会给出笼统的模糊警告,而是会详细解释:

- REQ对REQ:双方都希望从互相发送消息开始,并且只有在您对事情进行计时以便两个对等方同时交换消息的情况下,这才能工作。一想到它就会伤到我的大脑。

- REQ to DEALER:理论上可以这样做,但是如果添加第二个REQ,就会中断,因为DEALER无法向原始对等点发送回复。因此REQ socket 会混淆,并且/或返回针对其他客户机的消息。

- REP to REP::双方都会等待对方发出第一个信息。

- REP to ROUTER:理论上,如果 ROUTER socket知道REP socket 已经连接并且知道该连接的身份,ROUTER socket 可以启动对话框并发送正确格式的请求。这是混乱的,并没有增加超过经销商路由器(It’s messy and adds nothing over DEALER to ROUTER)。

在这个有效与无效的细分中,常见的线程是ZeroMQ socket 连接总是偏向于绑定到端点的一个对等点,以及连接到端点的另一个对等点。此外,哪边绑定哪边连接并不是任意的,而是遵循自然模式。我们期望“在那里”的那一面是绑定的:它将是一个服务器、一个代理、一个发布者和一个收集器。“来了又走”的一方将clients 和workers联系起来。记住这一点将帮助您设计更好的ZeroMQ架构。

探索Exploring ROUTER Sockets

让我们再仔细看看ROUTER sockets。我们已经看到了它们如何通过将单个消息路由到特定的连接来工作。我将更详细地解释如何识别这些连接,以及ROUTER sockets在不能发送消息时做什么。

Identities and Addresses

ZeroMQ中的标识概念特别指ROUTER sockets ,以及它们如何标识与其他socket的连接。 更广泛地说,身份在回复信封中用作地址。在大多数情况下,标识是任意的,并且是ROUTER sockets 的本地标识:它是哈希表中的一个查找键。独立地,对等点可以有物理地址(网络端点,如“tcp://192.168.55.117:5670”)或逻辑地址(UUID或电子邮件地址或其他惟一密钥)。

使用ROUTER sockets 与特定对等点通信的应用程序,如果已经构建了必要的散列表,则可以将逻辑地址转换为标识。因为ROUTER sockets 只在一个连接(到一个特定的对等点)发送消息时声明该连接的身份,所以您只能真正地回复一个消息,而不能自动地与一个对等点通信。

这是真的,即使你翻转规则,使ROUTER连接到对等点,而不是等待对等点连接到ROUTER。但是,您可以强制ROUTER sockets 使用逻辑地址来代替它的标识。zmq_setsockopt引用页面调用此设置socket标识。 其工作原理如下:

- 对等应用程序在绑定或连接之前设置其对等socket (DEALER 或REQ)的ZMQ_IDENTITY选项。

- 通常,对等点然后连接到已经绑定的 ROUTER socket。但是 ROUTER也可以连接到对等点。

- 在连接时,对等socket 告诉ROUTER socket,“请为这个连接使用这个标识”。

- 如果对等socket 没有这样说,ROUTER就为连接生成它通常的任意随机标识。

- ROUTER socket现在将此逻辑地址提供给应用程序,作为来自该对等点的任何消息的前缀标识帧。

- ROUTER 还期望逻辑地址作为任何传出消息的前缀标识帧。

下面是连接到ROUTER socket的两个对等点的简单例子,其中一个附加了一个逻辑地址“PEER2”:

C++ | C# | Clojure | CL | Delphi | Erlang | F# | Go | Haskell | Haxe | Java | Lua | Node.js | Perl | PHP | Python | Q | Ruby | Scala | Tcl | Ada | Basic | Felix | Objective-C | ooc | Racket

Here is what the program prints:

----------------------------------------[005] 006B8B4567[000][039] ROUTER uses a generated 5 byte identity----------------------------------------[005] PEER2[000][038] ROUTER uses REQ's socket identity

的错误处理 ROUTER Error Handling

ROUTER sockets确实有一种处理无法发送到任何地方的消息的方法:它们无声地丢弃这些消息。 这种态度在工作代码中是有意义的,但它使调试变得困难。“发送标识为第一帧”的方法非常棘手,以至于我们在学习时经常会出错,而ROUTER在我们出错时的死寂也不是很有建设性。

因为ZeroMQ v3.2中有一个socket选项可以设置为捕捉这个错误:ZMQ_ROUTER_MANDATORY。将其设置在ROUTER socket 上,然后当您在发送调用上提供不可路由的标识时,socket将发出EHOSTUNREACH错误的信号。

负载平衡模式The Load Balancing Pattern

现在让我们看一些代码。我们将看到如何将ROUTER socket连接到 REQ socket,然后连接到DEALER socket。这两个示例遵循相同的逻辑,即负载平衡模式。这种模式是我们第一次公开使用 ROUTER socket进行有意路由,而不是简单地充当应答通道。

负载平衡模式非常常见,我们将在本书中多次看到它。它解决了简单的循环式路由(如 PUSH和DEALER提供)的主要问题,即如果任务没有大致占用相同的时间,那么循环式路由就会变得低效。

这是邮局的比喻。如果每个柜台都有一个队列,有些人购买邮票(快速、简单的交易),有些人开立新帐户(非常慢的交易),那么您将发现邮票购买者被不公平地困在队列中。就像在邮局一样,如果您的消息传递体系结构是不公平的,人们会感到恼火。

邮局的解决方案是创建一个队列,这样即使一个或两个柜台工作缓慢,其他柜台将继续以先到先得的方式为客户服务。

PUSH和DEALER使用这种简单方法的一个原因是纯粹的性能。如果你到达美国任何一个主要机场,你会发现移民处排着长队。边境巡逻官员将提前派人在每个柜台排队,而不是使用单一队列。让人们提前走50码可以为每位乘客节省一到两分钟。由于每次护照检查的时间大致相同,所以或多或少是公平的。这是PUSH和DEALER的策略:提前发送工作负载,这样就有更少的旅行距离。

这是ZeroMQ反复出现的主题:世界上的问题是多种多样的,用正确的方法解决不同的问题可以让你受益。机场不是邮局,而且没有一个尺寸适合任何人,真的很好。 让我们回到一个worker (DEALER 或者 REQ)连接到一个broker (ROUTER)的场景。broker必须知道worker什么时候准备好了,并保存一个workers列表,以便每次可以使用最近最少使用的工人。

事实上,解决方案非常简单:工作人员在开始和完成每个任务后都会发送一条“ready”消息。broker逐个读取这些消息。每次读取一条消息时,它都是从最后一个使用的worker中读取的。因为我们使用的是ROUTER socket,我们得到一个标识,然后我们可以用它把一个任务发送回worker。 这是request-reply的一个曲解,因为任务与应答一起发送,任务的任何响应都作为一个新请求发送。下面的代码示例应该更清楚。

ROUTER Broker and REQ Workers

下面是一个负载平衡模式的例子,使用ROUTER broker与一组REQ workers对话:

C++ | C# | Clojure | CL | Delphi | Erlang | F# | Go | Haskell | Haxe | Java | Lua | Node.js | Perl | PHP | Python | Ruby | Scala | Tcl | Ada | Basic | Felix | Objective-C | ooc | Q | Racket

该示例运行5秒,然后每个工作人员打印他们处理了多少任务。如果路由成功了,我们希望工作得到公平分配:

Completed: 20 tasksCompleted: 18 tasksCompleted: 21 tasksCompleted: 23 tasksCompleted: 19 tasksCompleted: 21 tasksCompleted: 17 tasksCompleted: 17 tasksCompleted: 25 tasksCompleted: 19 tasks

要与本例中的工作人员对话,我们必须创建一个对 REQ-friendly的信封,它由一个标识符和一个空信封分隔符框架组成。

Figure 31 - Routing Envelope for REQ

ROUTER Broker and DEALER Workers

任何地方你可以使用REQ,你就可以使用DEALER。有两个具体的区别:

- REQ socket总是在任何数据帧之前发送一个空的分隔符帧;DEALER没有。

- REQ socket在收到回复之前只发送一条消息;DEALER是完全异步的。

同步和异步行为对我们的示例没有影响,因为我们正在执行严格的请求-应答。当我们处理从失败中恢复时,它更相关,我们将在 Reliable Request-Reply Patterns中讨论这个问题。现在让我们看看完全相同的例子,但与REQ socket替换为一个DEALER socket:

rtdealer: ROUTER-to-DEALER in C

C++ | C# | Clojure | CL | Delphi | Erlang | F# | Go | Haskell | Haxe | Java | Lua | Node.js | Perl | PHP | Python | Ruby | Scala | Tcl | Ada | Basic | Felix | Objective-C | ooc | Q | Racket

代码几乎是相同的,除了worker使用一个DEALER socket,并读写数据帧之前的空帧。 当我想要保持与REQ worker的兼容性时,我使用这种方法。

但是,请记住空分隔符帧的原因:它允许多跳扩展请求在 REP socket中终止, REP socket使用该分隔符分隔应答信封,以便将数据帧传递给应用程序。

如果我们从来不需要将消息传递给REP socket,我们可以简单地在两边删除空分隔符框架,这使事情变得更简单。这通常是我为纯DEALER to ROUTER协议使用的设计。

负载平衡消息代理 A Load Balancing Message Broker

前面的示例只完成了一半。它可以用虚拟的请求和响应来管理一组工人,但是它没有办法与clients交谈。如果我们添加第二个接收clients请求的frontend ROUTER socket,并将我们的示例转换为一个可以将消息从前端切换到后端的代理,我们将得到一个有用的、可重用的小型负载平衡消息代理。

Figure 32 - Load Balancing Broker

该代理执行以下操作:

- 接受来自一组clients的连接。

- 接受来自一组workers的连接。

- 接受来自clients的请求,并将这些请求保存在一个队列中。

- 使用负载平衡模式将这些请求发送给workers 。

- 收到workers的回复。

- 将这些响应发送回原始请求client。

理代码相当长,但值得理解:

lbbroker: Load balancing broker in C

C++ | C# | Clojure | CL | Delphi | Erlang | F# | Go | Haskell | Haxe | Java | Lua | Node.js | Perl | PHP | Python | Ruby | Scala | Tcl | Ada | Basic | Felix | Objective-C | ooc | Q | Racket

这个程序最困难的部分是(a)每个socket 读取和写入的信封,以及(b)负载平衡算法。我们将依次从消息信封格式开始。

让我们遍历一个完整的请求-响应链,从client 到worker,然后返回。在这段代码中,我们设置了client 和worker sockets 的标识,以便更容易地跟踪消息帧。实际上,我们允许 ROUTER sockets为连接创建身份。假设客户机的标识是“client”,而worker的标识是“worker”。客户机应用程序发送一个包含“Hello”的帧。

Figure 33 - Message that Client Sends

Because the REQ socket adds its empty delimiter frame and the ROUTER socket adds its connection identity, the proxy reads off the frontend ROUTER socket the client address, empty delimiter frame, and the data part.

Figure 34 - Message Coming in on Frontend

The broker sends this to the worker, prefixed by the address of the chosen worker, plus an additional empty part to keep the REQ at the other end happy.

Figure 35 - Message Sent to Backend

This complex envelope stack gets chewed up first by the backend ROUTER socket, which removes the first frame. Then the REQ socket in the worker removes the empty part, and provides the rest to the worker application.

Figure 36 - Message Delivered to Worker

//直译了==> 需修改 工作人员必须保存信封(信封是到空消息框为止的所有部分,包括空消息框),然后才能对数据部分执行所需的操作。请注意,REP套接字会自动执行此操作,但我们使用的是REQ-ROUTER模式,因此我们可以获得适当的负载平衡。

在返回路径上,消息与传入时相同,即,后端套接字将消息分成五部分发送给代理,代理将消息分成三部分发送给前端套接字,客户端将消息分成一个部分。

现在让我们看看负载平衡算法。它要求客户端和工作人员都使用REQ套接字,并且工作人员在收到消息时正确地存储和重放信封。该算法是:

- 创建一个poll集,它总是轮询后端,只有当有一个或多个工作人员可用时才轮询前端。

- 轮询具有无限超时的活动。

- 如果后端有活动,我们要么有一个“就绪”消息,要么有一个客户端的回复。在这两种情况下,我们都将worker地址(第一部分)存储在worker队列中,如果其余部分是客户机应答,则通过前端将其发送回客户机。

- 如果前端有活动,我们接收客户机请求,弹出下一个worker(最后使用的),并将请求发送到后端。这意味着发送worker地址、空部分以及客户机请求的三个部分。

您现在应该看到,您可以重用和扩展负载平衡算法,并根据工作人员在其初始“就绪”消息中提供的信息进行更改。例如,工作人员可能启动并进行性能自我测试,然后告诉代理他们的速度有多快。然后,代理可以选择可用的最快的工人,而不是最老的工人。

| A High-Level API for ZeroMQ | top prev next |

|---|---|

我们将把request-reply推入堆栈并打开另一个区域,即ZeroMQ API本身。这样做是有原因的:当我们编写更复杂的示例时,底层ZeroMQ API看起来越来越笨拙。看看我们的负载平衡代理的工作线程的核心:

**while** (true) {` `*// Get one address frame and empty delimiter*` `char *address = s_recv (worker);` `char *empty = s_recv (worker);` `assert (*empty == 0);` `free (empty);` `*// Get request, send reply*` `char *request = s_recv (worker);` `printf ("Worker: %s**\n**", request);` `free (request);` `s_sendmore (worker, address);` `s_sendmore (worker, "");` `s_send` `(worker, "OK");` `free (address);}

该代码甚至不能重用,因为它只能处理信封中的一个回复地址,而且它已经对ZeroMQ API进行了一些包装。如果我们使用libzmq简单消息API,我们必须这样写:

**while** (true) {` `*// Get one address frame and empty delimiter*` `char address [255];` `int address_size = zmq_recv (worker, address, 255, 0);` `**if** (address_size == -1)` `**break**;` `char empty [1];` `int empty_size = zmq_recv (worker, empty, 1, 0);` `assert (empty_size <= 0);` `**if** (empty_size == -1)` `**break**;` `*// Get request, send reply*` `char request [256];` `int request_size = zmq_recv (worker, request, 255, 0);` `**if** (request_size == -1)` `**return** NULL;` `request [request_size] = 0;` `printf ("Worker: %s**\n**", request);` `` `zmq_send (worker, address, address_size, ZMQ_SNDMORE);` `zmq_send (worker, empty, 0, ZMQ_SNDMORE);` `zmq_send (worker, "OK", 2, 0);}

当代码太长而不能快速编写时,理解它也太长。到目前为止,我一直坚持使用本机API,因为作为ZeroMQ用户,我们需要深入了解这一点。但当它阻碍我们的时候,我们必须把它当作一个需要解决的问题。

当然,我们不能仅仅更改ZeroMQ API,这是一个文档化的公共契约,成千上万的人同意并依赖它。相反,我们基于到目前为止的经验,尤其是编写更复杂的请求-应答模式的经验,在顶层构建一个更高级别的API。

我们想要的是一个API,它允许我们一次性接收和发送完整的消息,包括包含任意数量回复地址的回复信封。它让我们用最少的代码行来做我们想做的事情。

创建一个好的消息API相当困难。我们有一个术语问题:ZeroMQ使用“message”来描述多部分消息和单个消息框架。我们有一个期望问题:有时将消息内容视为可打印的字符串数据是很自然的,有时将其视为二进制块。我们面临着技术上的挑战,尤其是如果我们想避免过多地复制数据的话。

尽管我的特定用例是C语言,但制作一个好的API所面临的挑战影响到所有的语言。无论您使用哪种语言,请考虑如何为您的语言绑定做出贡献,使其与我将要描述的C绑定一样好(或更好)。

Features of a Higher-Level API

My solution is to use three fairly natural and obvious concepts: string (already the basis for our s_send and s_recv) helpers, frame (a message frame), and message (a list of one or more frames). Here is the worker code, rewritten onto an API using these concepts:

while (true) {

`zmsg_t *msg = zmsg_recv (worker); zframe_reset (zmsg_last (msg), "OK", 2); `zmsg_send (&msg, worker);

}

Cutting the amount of code we need to read and write complex messages is great: the results are easy to read and understand. Let’s continue this process for other aspects of working with ZeroMQ. Here’s a wish list of things I’d like in a higher-level API, based on my experience with ZeroMQ so far:

Automatic handling of sockets. I find it cumbersome to have to close sockets manually, and to have to explicitly define the linger timeout in some (but not all) cases. It’d be great to have a way to close sockets automatically when I close the context.

Portable thread management. Every nontrivial ZeroMQ application uses threads, but POSIX threads aren’t portable. So a decent high-level API should hide this under a portable layer.

Piping from parent to child threads. It’s a recurrent problem: how to signal between parent and child threads. Our API should provide a ZeroMQ message pipe (using PAIR sockets and

inprocautomatically.Portable clocks. Even getting the time to a millisecond resolution, or sleeping for some milliseconds, is not portable. Realistic ZeroMQ applications need portable clocks, so our API should provide them.

A reactor to replace zmq_poll(). The poll loop is simple, but clumsy. Writing a lot of these, we end up doing the same work over and over: calculating timers, and calling code when sockets are ready. A simple reactor with socket readers and timers would save a lot of repeated work.

Proper handling of Ctrl-C. We already saw how to catch an interrupt. It would be useful if this happened in all applications.

| The CZMQ High-Level API | top prev next |

|---|---|