Item 41: Respect the contract of hashCode

Another method from Any that we can override is hashCode. First, let’s explain why we need it. The hashCode function is used in a popular data structure called hash table, which is used in a variety of different collections or algorithms under the hood.

Hash table

Let’s start with the problem hash table was invented to solve. Let’s say that we need a collection that quickly both adds and finds elements. An example of this type of collection is a set or map, neither of which allow for duplicates. So whenever we add an element, we first need to look for an equal element.

A collection based on an array or on linked elements is not fast enough for checking if it contains an element, because to check that we need to compare this element with all elements on this list one after another. Imagine that you have an array with millions of pieces of text, and now you need to check if it contains a certain one. It will be really time-consuming to compare your text one after another with those millions.

A popular solution to this problem is a hash table. All you need is a function that will assign a number to each element. Such a function is called a hash function and it must always return the same value for equal elements. Additionally, it is good if our hash function:

- Is fast

- Ideally returns different values for unequal elements, or at least has enough variation to limit collisions to a minimum

Such a function categorizes elements into different buckets by assigning a number to each one. What is more, based on our requirement for the hash function, all elements equal to each other will always be placed in the same bucket. Those buckets are kept in a structure called hash table, which is an array with a size equal to the number of buckets. Every time we add an element, we use our hash function to calculate where it should be placed, and we add it there. Notice that this process is very fast because calculating the hash should be fast, and then we just use the result of the hash function as an index in the array to find our bucket. When we search for an element, we find its bucket the same way and then we only need to check if it is equal to any element in this bucket. We don’t need to check any other bucket, because the hash function must return the same value for equal elements. This way, at a low cost, it divides the number of operations needed to find an element by the number of buckets. For instance, if we have 1,000,000 elements and 1,000 buckets, searching for duplicates only requires to compare about 1,000 elements on average, and the performance cost of this improvement is really small.

To see a more concrete example, let’s say that we have the following strings and a hash function that splits into 4 buckets:

| Text | Hash code |

|---|---|

| “How much wood would a woodchuck chuck” | 3 |

| “Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers” | 2 |

| “Betty bought a bit of butter” | 1 |

| “She sells seashells by the seashore” | 2 |

Based on those numbers, we will have the following hash table built:

| Index | Object to which hash table points |

|---|---|

| 0 | [] |

| 1 | [“Betty bought a bit of butter”] |

| 2 | [“Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers”, “She sells seashells by the seashore” ] |

| 3 | [“How much wood would a woodchuck chuck”] |

Now, when we are checking if a new text is in this hash table, we are calculating its hash code. If it is equal to 0, then we know that it is not on this list. If it is either 1 or 3, we need to compare it with a single text. If it is 2, we need to compare it with two pieces of text.

This concept is very popular in technology. It is used in databases, in many internet protocols, and also in standard library collections in many languages. In Kotlin/JVM both the default set (LinkedHashSet) and default map (LinkedHashMap) use it. To produce a hash code, we use the hashCode function4.

Problem with mutability

Notice that a hash is calculated for an element only when this element is added. An element is not moved when it mutates. This is why both LinkedHashSet and LinkedHashMap key will not behave properly when an object mutates after it has been added:

data class FullName(var name: String,var surname: String)val person = FullName("Maja", "Markiewicz")val s = mutableSetOf<FullName>()s.add(person)person.surname = "Moskała"print(person) // FullName(name=Maja, surname=Moskała)print(person in s) // falseprint(s.first() == person) // true

This problem was already noted on Item 1: Limit mutability: Mutable objects are not to be used in data structures based on hashes or on any other data structure that organizes elements based on their mutable properties. We should not use mutable elements for sets or as keys for maps, or at least we should not mutate elements that are in such collections. This is also a great reason to use immutable objects in general.

The contract of hashCode

Knowing what we need hashCode for, it should be clear how we expect it to behave. The formal contract is as follows (Kotlin 1.3.11):

- Whenever it is invoked on the same object more than once, the

hashCodemethod must consistently return the same integer, provided no information used inequalscomparisons on the object is modified. - If two objects are equal according to the

equalsmethod, then calling thehashCodemethod on each of the two objects must produce the same integer result.

Notice that the first requirement is that we need hashCode to be consistent. The second one is the one that developers often forget about, and that needs to be highlighted: hashCode always needs to be consistent with equals, and equal elements must have the same hash code. If they don’t, elements will be lost in collections using a hash table under the hood:

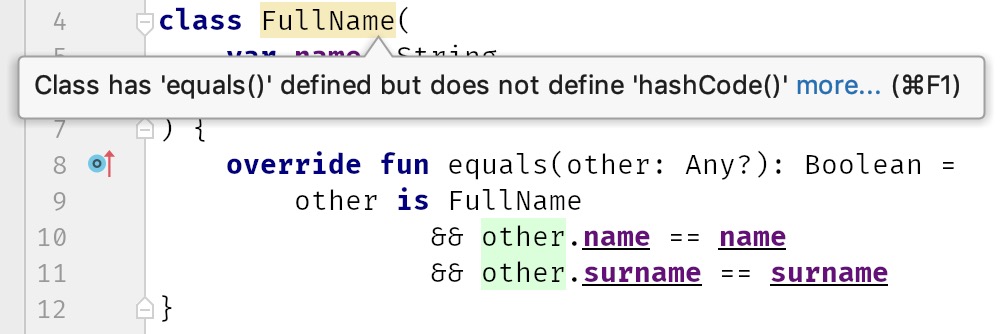

class FullName(var name: String,var surname: String) {override fun equals(other: Any?): Boolean =other is FullName&& other.name == name&& other.surname == surname}val s = mutableSetOf<FullName>()s.add(FullName("Marcin", "Moskała"))val p = FullName("Marcin", "Moskała")print(p in s) // falseprint(p == s.first()) // true

This is why Kotlin suggests overriding hashCode when you have a custom equals implementation.

There is also a requirement that is not required, but very important if we want this function to be useful. hashCode should spread elements as widely as possible. Different elements should have the highest possible probability of having different hash values.

Think about what happens when many different elements are placed in the same bucket - there is no advantage in using a hash table! An extreme example would be making hashCode always return the same number. Such a function would always place all elements into the same bucket. This is fulfilling the formal contract, but it is completely useless. There is no advantage to using a hash table when hashCode always returns the same value. Just take a look at the examples below where you can see a properly implemented hashCode, and one that always returns 0. For each equals we added a counter that counts how many times it was used. You can see that when we operate on sets with values of both types, the second one, named Terrible, requires many more comparisons:

class Proper(val name: String) {override fun equals(other: Any?): Boolean {equalsCounter++return other is Proper && name == other.name}override fun hashCode(): Int {return name.hashCode()}companion object {var equalsCounter = 0}}class Terrible(val name: String) {override fun equals(other: Any?): Boolean {equalsCounter++return other is Terrible && name == other.name}// Terrible choice, DO NOT DO THAToverride fun hashCode() = 0companion object {var equalsCounter = 0}}val properSet = List(10000) { Proper("$it") }.toSet()println(Proper.equalsCounter) // 0val terribleSet = List(10000) { Terrible("$it") }.toSet()println(Terrible.equalsCounter) // 50116683Proper.equalsCounter = 0println(Proper("9999") in properSet) // trueprintln(Proper.equalsCounter) // 1Proper.equalsCounter = 0println(Proper("A") in properSet) // falseprintln(Proper.equalsCounter) // 0Terrible.equalsCounter = 0println(Terrible("9999") in terribleSet) // trueprintln(Terrible.equalsCounter) // 4324Terrible.equalsCounter = 0println(Terrible("A") in terribleSet) // falseprintln(Terrible.equalsCounter) // 10001

Implementing hashCode

We define hashCode in Kotlin practically only when we define custom equals. When we use the data modifier, it generates both equals and a consistent hashCode. When you do not have a custom equals method, do not define a custom hashCode unless you are sure you know what you are doing and you have a good reason. When you have a custom equals, implement hashCode that always returns the same value for equal elements.

If you implemented typical equals that checks equality of significant properties, then a typical hashCode should be calculated using the hash codes of those properties. How can we make a single hash code out of those many hash codes? A typical way is that we accumulate them all in a result, and every time we add the next one, we multiply the result by the number 31. It doesn’t need to be exactly 31, but its characteristics make it a good number for this purpose. It is used this way so often that now we can treat it as a convention. Hash codes generated by the data modifier are consistent with this convention. Here is an example implementation of a typical hashCode together with its equals:

class DateTime(private var millis: Long = 0L,private var timeZone: TimeZone? = null) {private var asStringCache = ""private var changed = falseoverride fun equals(other: Any?): Boolean =other is DateTime &&other.millis == millis &&other.timeZone == timeZoneoverride fun hashCode(): Int {var result = millis.hashCode()result = result * 31 + timeZone.hashCode()return result}}

One helpful function on Kotlin/JVM is Objects.hash, that calculates hash of multiple objects using the same algorithm as presented above:

override fun hashCode(): Int =Objects.hash(timeZone, millis)

There is no such function in the Kotlin stdlib, but if you need it on other platforms you can implement it yourself:

override fun hashCode(): Int =hashCodeFrom(timeZone, millis)inline fun hashCodeOf(vararg values: Any?) =values.fold(0) { acc, value ->(acc * 31) + value.hashCode()}

The reason why such a function is not in the stdlib is that we rarely need to implement hashCode ourselves. For instance, in the DateTime class presented above, instead of implementing equals and hashCode ourselves, we can just use data modifier:

data class DateTime2(private var millis: Long = 0L,private var timeZone: TimeZone? = null) {private var asStringCache = ""private var changed = false}

When you do implement hashCode, remember that the most important rule is that it always needs to be consistent with equals, and it should always return the same value for elements that are equal.